Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO)

A complex finance product derivative whose underlying value is derived from an underlying asset, backed by a collection of loans and other assets.

What Is a Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO)?

Collateralized debt obligations are derivatives whose underlying value is derived from an underlying asset. This debt obligation is complex finance product that is backed by a collection of loans and other assets.

Collateral Debt Obligations (CDOs) are held by financial institutions and sold to investors, offering diversification and liquidity. However, this instrument is particularly risky and not suitable for other investors.

CDOs are created by investment bankers, who gather cash flow-generating assets like mortgages, bonds, and other classifications of debts. These are repackaged into different tranches based on the level of credit risk assumed by the investor.

Originally developed as instruments for corporate development, between 2000 and 2010, CDOs became like vehicles to refinance Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS).

A CDO can be assumed as a promise to pay investors in a said sequence, like different private labels secured securities based on the cash flows collected by CDOs from the collection of bonds or assets.

Key Takeaways

- Collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) are intricate financial instruments, classified as derivatives, with underlying values derived from a pool of diverse assets such as loans.

- CDOs are crafted by investment bankers who assemble cash flow-generating assets like mortgages, bonds, and various debt classifications.

- The CDOs were originally designed for corporate development; between 2000 and 2010, CDOs evolved into vehicles to refinance Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS).

- CDOs are supported by financial instruments like bonds, loans, and debt instruments, classified based on credit quality. They consist of multiple tranches, each with distinct risk and return profiles.

Understanding Collateralized debt obligations (CDOs)

The CDOs vary in structure and underlying assets, also the basic principles here are the same. A CDO can also be called as asset-backed securities.

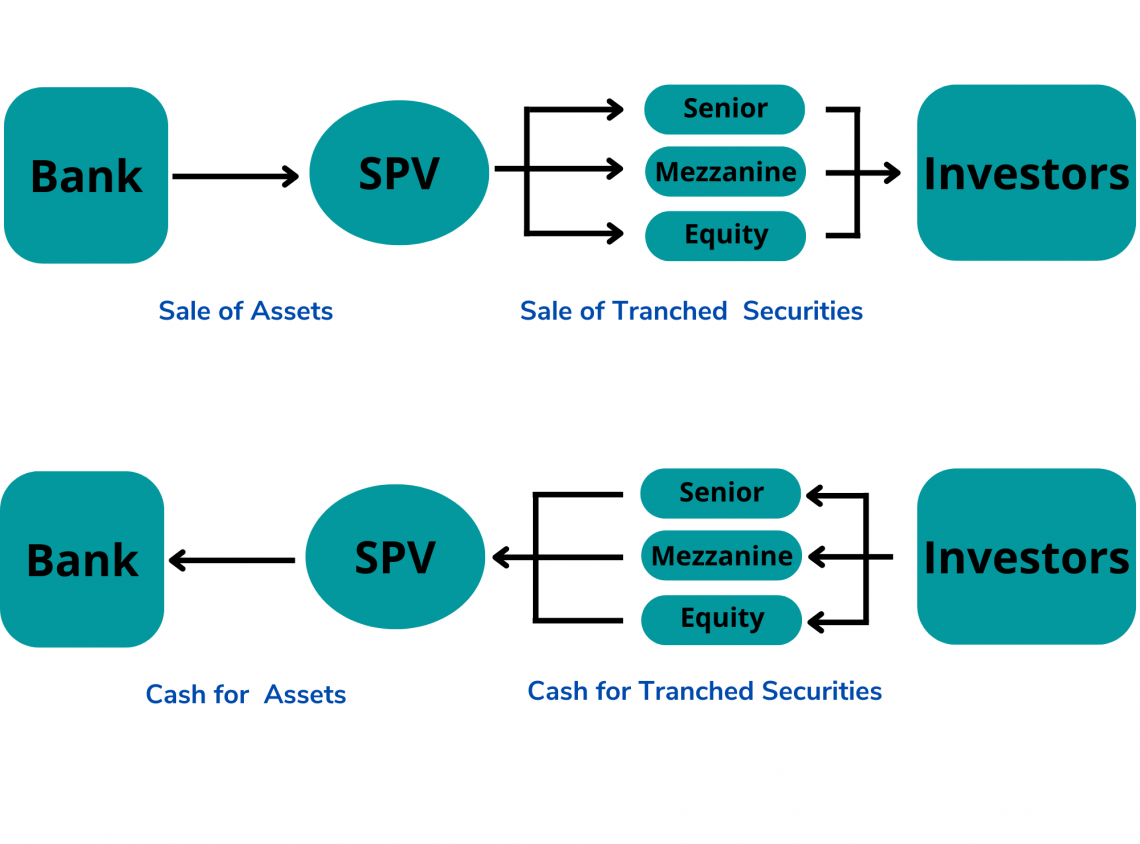

To create a CDO, a corporation is constructed to hold assets as collateral supporting cash flows which are sold to investors.

A sequence in the formation of a CDO is as follows:

- A Special Purpose Entity (SPE) is designed and formulated to acquire a portfolio of underlying assets. These common underlying assets may include mortgage-backed securities, commercial real estate, and commercial loans

- Investors receive bonds from the SPE in return for cash, which is utilized to buy the portfolio of underlying assets.

- The bonds are not homogeneous; instead, they are issued in layers known as tranches, each having distinct risk characteristics, just like other ABS private label instruments.

- Prior to junior and equity tranches, senior tranches are paid from the cash flows from the underlying assets.

- The equity tranches bear losses initially, followed by the junior tranches and then the senior tranches.

A common analogy used to describe the cash flows of the CDOs is the water flowing through the cups of the investors to different tranches. These cash flows can be mortgage payments from mortgage-backed securities.

Where the cups of senior investor tranches are filled first, later junior, and finally, the junior most tranches, that is, equity tranches. So, in case of default of mortgages, the cups aren't filled, right from the original investor to the equity tranches.

An investor in a CDO faces risk and return contingent on the underlying assets as well as the way the tranches are defined. The investment is specifically dependent on the presumptions and techniques employed to determine the risk and return of the tranches.

The originators of the underlying assets can transfer credit risk to another institution or to individual investors through CDOs, as they can with other asset-backed securities. Investors need to be aware of how CDO risk is determined.

Equity layer tranches issued by other CDOs made up the entirety of the assets owned by one CDO in certain instances.

Because the equity layer tranches were paid last in the payment sequence and there was insufficient cash flow from the underlying subprime mortgages (many of which defaulted), certain CDOs became completely worthless.

In the end, precisely estimating the risk and return features of these structures presents a difficulty.

There have been significant advancements in modeling methodologies that more correctly capture the dynamics of these complex securities since the publication of David Li's 2001 model.

Advantages and Disadvantages of CDOs

CDOs have advantages and disadvantages, just like any other kind of asset.

Their two primary drawbacks—their intricacy, which made it challenging to appropriately evaluate them—and their susceptibility to repayment risk, particularly from subprime borrowers, contributed to their involvement in the housing bubble and the subprime mortgage crisis.

Advantages Of CDOs

- Liquidity: CDOs provide investors with enhanced liquidity by providing them the ability to quickly liquidate their holdings.

- Risk Diversification: The collection of debt and other debt instruments make the CDOs an investment with diversified risk.

- Repayment Priority: If invested in the senior tranche of debts, the investor can be guaranteed priority in the repayment.

Disadvantages Of CDOs

- Complexity: The complexity in the structure and the investor's inability to understand the workings of the CDOs makes it very unattractive to investors sometimes.

- Risk Of Devaluation: Investors may face risks if the underlying assets of CDOs default or lose creditworthiness. This could have a negative effect on the asset value.

- Historical Crisis Impact: CDOs were blamed for starting the global housing market collapse in 2008, which resulted in huge losses for investors. CDOs were a major contributor to the 2008 financial crisis.

Structure of Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs)

The collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) are a complex financial instrument that gained popularity during the 2007-08 financial crisis. These structured financial products are secured by a diversified collection of debt securities.

CDOs are structured with multiple tranches, each with a distinct risk and return profile. An outline of a typical collateralized debt obligation structure is provided below:

Collateral Pool

CDOs are particularly supported and secured by financial instruments and assets, like bonds, loans, and other debt instruments.

These financial assets/instruments are collateral for the CDOs and are typically classified based on their credit quality.

Tranches

CDOs are divided based on the tranches. A tranche is a piece or part of something, usually money. For example, an installment payment is a tranche of a loan.

Each tranche represents a piece of the overall investment in the asset and has a specific level of seniority.

- Senior Tranche: Also known as senior bonds. These bonds are the senior-most in the hierarchy under tranches. These bonds have the highest claim in the cash flows generated through the underlying asset.

- Mezzanine Tranche: Second in the level of seniority under the tranches. Carries a high-level of risks attached. But, at the very same time carries high-returns but is more susceptible to losses in the collateral collection.

- Equity Tranche: The most hazardous component of the CDO structure is the equity tranche. Following the senior and mezzanine tranches, it absorbs losses. Although there is a greater default risk, investors in this tranche could see larger profits.

Credit Enhancement

Credit enhancement methods are commonly incorporated into CDOs in order to draw in investors and secure improved credit ratings for the senior tranches.

These can include subordination, which assigns losses to lesser tranches first, over-collateralization, which adds more assets than necessary to protect the senior tranche; and different financial products like credit default swaps.

Cash Flow Waterfall

Senior tranches receive the payments first in the order, whereas the subsequent payments are to mezzanine and equity tranches. In the event of losses in the collateral pool, they are absorbed by the hierarchy in the reverse order.

The cash flows generated by the CDOs are to follow the waterfall structure mentioned above.

Manager

The manager of a CDO is normally in charge of choosing and overseeing the assets in the collateral pool. This manager is frequently an investment manager or a special purpose organization.

In order to maximize profits for investors and follow the investing parameters specified in the CDO's prospectus, the manager's role is essential.

The intricacy and transparency of CDO structures are noteworthy because they made it difficult for investors to determine the actual risk exposure of these instruments, which exacerbated the difficulties encountered during the financial crisis.

The CDO-related events contributed significantly to the 2007–2008 global financial crisis.

Example of an ABS CDO

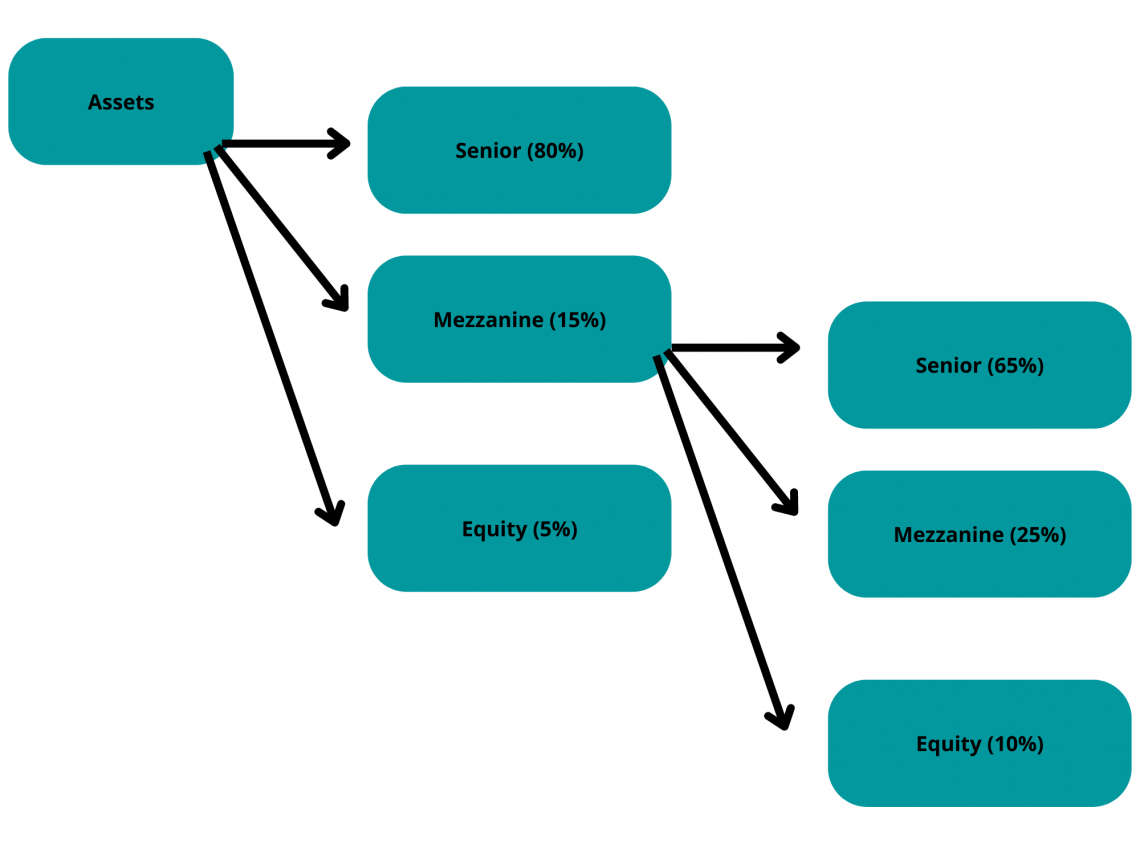

An example of the Asset-Backed Security Collateral Debt Obligation (ABS CDO) encompasses the creation of a "Mezz" ABS CDO originating from the BBB tranches from the ABS.

In the provided scenario, the mezzanine tranches are used to create the ABS CDO of an Asset-Backed Security (ABS) that especially focuses on the BBB-rated tranches.

This explains how ABS CDOs can be structured utilizing different classifications of tranches of asset-backed securities to create diversified investment collection with carrying risk and return profile.

An ABS CDO, often known as a Mezz ABS CDO, is the resulting structure.

In this example, the equity tranche represents the remaining 10% of the principal, the mezzanine tranche represents 25% of the principal, and the senior tranche of the ABS CDO represents 65% of the principal of the ABS mezzanine tranches.

The agreement is designed to grant the senior tranche of the ABS CDO the highest credit rating of AAA. This shows that roughly 90% of the total principal of the AAA-rated instruments is generated in the instance under consideration.

This might sound high, but if the securitization went on and an ABS was created from ABS CDO tranches, the proportion would be further increased.

Cash vs. synthetic Collateralized debt obligations

Cash Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) involve a portfolio of cash assets like loans, corporate bonds, mortgage-backed securities, or asset-backed securities.

The ownership of such securities is transferred to a legal entity issuing CDO tranches.

Whereas Synthetic CDOs, don't own any cash assets, but gain from derivatives credit default swaps (CDS) without owning the underlying asset the risk exposure.

Let us discuss some of the differences between the two types of CDOs.

| Aspect | Cash CDOs | Synthetic CDOs |

|---|---|---|

| Funding | Senior tranche investors receive periodic payments without capital investment. Junior tranches may require capital contributions in case of losses. | Investors receive premium payments for assuming the risk of loss on specific assets in the event of default. With different tranches having different levels of risk. |

| Creation | These CDOs require purchasing and managing physical assets, making them more time-consuming to create compared to synthetic CDOs. | Unlike cash CDOs, which require the acquisition and management of tangible assets, synthetic CDOs can be created more quickly. Their exposure to credit risk is derived from derivatives. |

| Ownership | Direct ownership of the assets. | Synthetic CDOs create credit exposure through these financial derivatives. |

| Risk Exposure | Investors are exposed to physical asset performance. | Investors here experience risk associated with derivative risks. |

| Complexity | Complex and expensive to create. | Cheaper and easier to create when compared to cash CDOs. |

The 2007 Credit crisis

Understanding the relationship between Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) and the credit crisis of 2007–2008 is essential to figuring out what caused the financial instability during that time.

Collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs, were a major contributor to the financial unrest of the 2007 credit crisis. Here is an overview.

Role In The Crisis

CDOs were combined and sold to investors with subprime mortgages, which were frequently deemed safer than they truly were.

This resulted in a huge housing bubble and ultimately fueled the worst economic crisis the United States has experienced since the Great Depression.

By 2009, over half of the tranches that were rated as most safe (triple-A) and issued between 2005 and 2007 had either lost principal or been downgraded to junk status.

In comparison, a tiny percentage of triple-A tranches of Alt-A or subprime mortgage-backed securities were doomed to similar outcomes.

Market Impact

About $386 billion worth of CDOs were issued in 2006 and 2007. However, by the end of 2007 and into 2008, the market essentially vanished since CDOs were seen as hazardous.

Significant losses resulted from the crisis for the institutions holding CDOs. For example, Merrill Lynch recorded losses of $2.2 billion during the third quarter of 2007.

Regulatory Response

Congress addressed the crisis by approving the Troubled Asset Relief Programme (TARP), a $700 billion bailout program designed to stabilize financial institutions that were having trouble as a result of subprime loan defaults.

Post-Crisis Emergence

It is anticipated that the CDO market will grow during the 2020s and hit $158.5 billion by 2026. However, there are still concerns about whether the same dangers associated with trading CDOs have received enough attention.

The risks and complexity of these structured finance instruments are brought to light by the subprime mortgage packaging that CDOs participated in and the subsequent effects these mortgages had on the financial system during the 2007 Credit Crisis.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?