Naked Call

A specific strategy used by investors who are bearish on the underlying security.

What is a Naked Call?

A naked call is a specific strategy used by investors who are bearish on the underlying security. This type of options trade involves selling an option contract of a security that the investor does not hold equivalent units of.

In simple terms, an investor using this strategy is essentially betting that the price at expiration will be below the option's strike price (more on this later). Any price at expiration above the strike would mean fewer profits or even a loss on the trade.

Because this strategy is based on selling a contract, the primary goal is to collect the contract premium.

Other selling strategies, such as the covered call, require an investor to hold units equivalent to the number of units commanded by the option (usually 100 shares for stock options). These are reserved for if the option is exercised.

Because these shares are not held, the investor is considered "naked." If the stock price jumps sharply, the investor could be left with a devastating loss, as they have no protection from a downward price shift.

In summary, these are the most important things to take note of when using the naked call strategy:

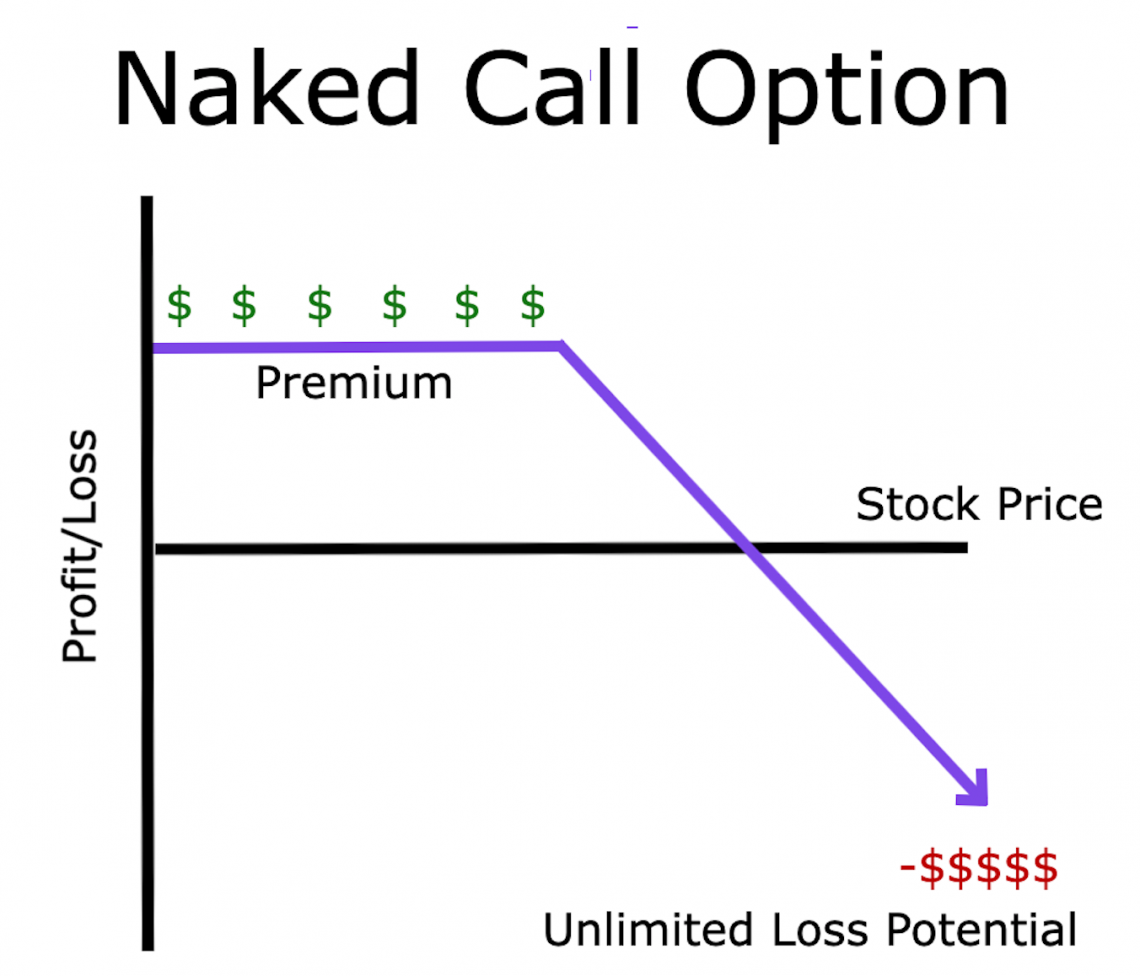

- The profit is capped at the premium earned immediately after the contract is sold.

- The losses are unlimited (it is a risky strategy).

- The investor is betting on a downward price movement direction; they are bearish.

Call Option Basics

A call option is a type of financial instrument used to speculate on the price of a security. Like other option contracts, its value is determined by changes in the underlying security price.

An equity call option generally gives the right to buy 100 shares of the underlying security for a set price up until the expiration of the contract.

There are a ton of specificities that determine how an option contract is priced and its value changes.

To understand the bare bones of the contract and how it works, investors must know only a few key components. These include:

- Strike Price

- Expiration Date

- Premium

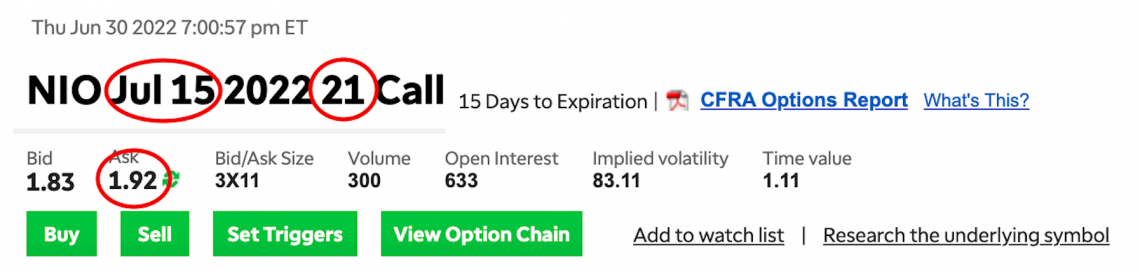

For this NIO option, the strike price is $21, the expiration date is July 15, 2022, and the premium for buyers is $1.92, also known as the ask.

The strike price is the price that determines the contract’s money. For a given call option, a market price of the underlying above the strike price would mean the agreement is in the money. A market price below the strike would suggest it is out of the money.

The expiration date is the date at which the option expires. It can no longer be exercised after that date. Contracts are typically only exercised when in the money, as there is no benefit to exercising an at-the-money or out-of-the-money contract. The investor would most likely lose money from exercising one of these options.

It is also worth noting that some forms of options can be exercised before expiration, like the American option, but this is unusual. Instead, investors typically choose to close their position by selling the option to another investor or purchasing back the sold option if they create a short position.

The premium is the price of purchasing the option. It is expressed as a price per share, meaning that an option with a $4.50 premium would cost a purchaser $450. $4.50 for each of the 100 shares in the contract.

Contract Price = Premium x 100 shares

This premium is essentially the price an investor is willing to pay to have the leverage of 100 shares temporarily. Instead of needing capital to purchase 100 shares, an investor must pay the premium for the option.

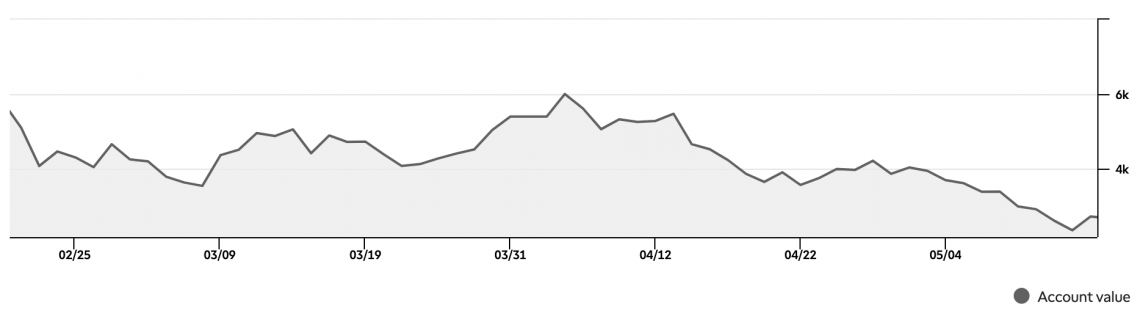

Because the contract represents 100 shares, its value can change rapidly, especially as the option nears expiration. As a whole, this can lead to portfolio volatility if the contract has a high portfolio weight.

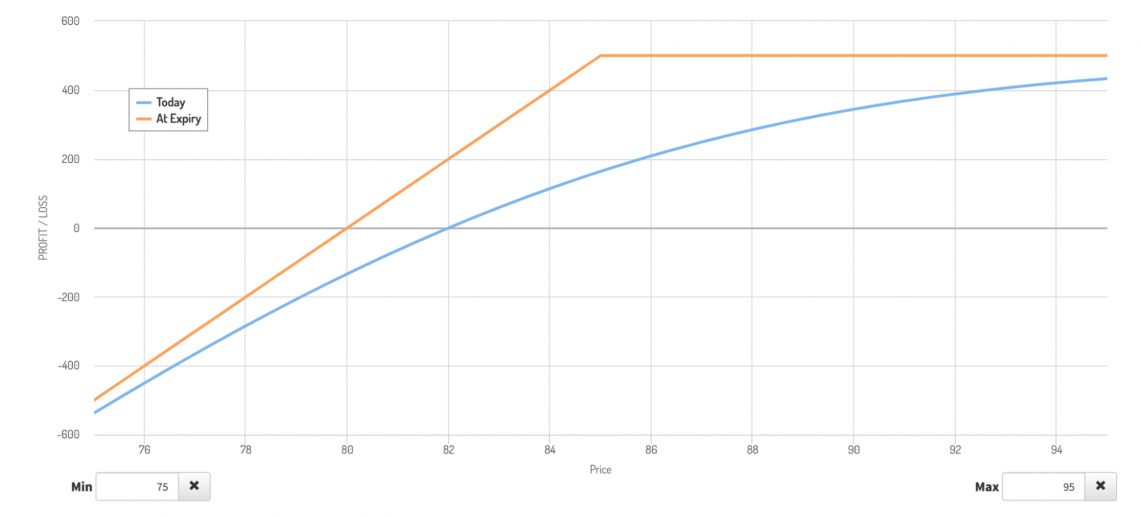

Buying a Call

As mentioned earlier, a call option gives the owner the right to buy 100 shares of a company at a specific price at a particular time. Therefore, someone purchasing a call option by itself is both hoping for and expecting an increase in price.

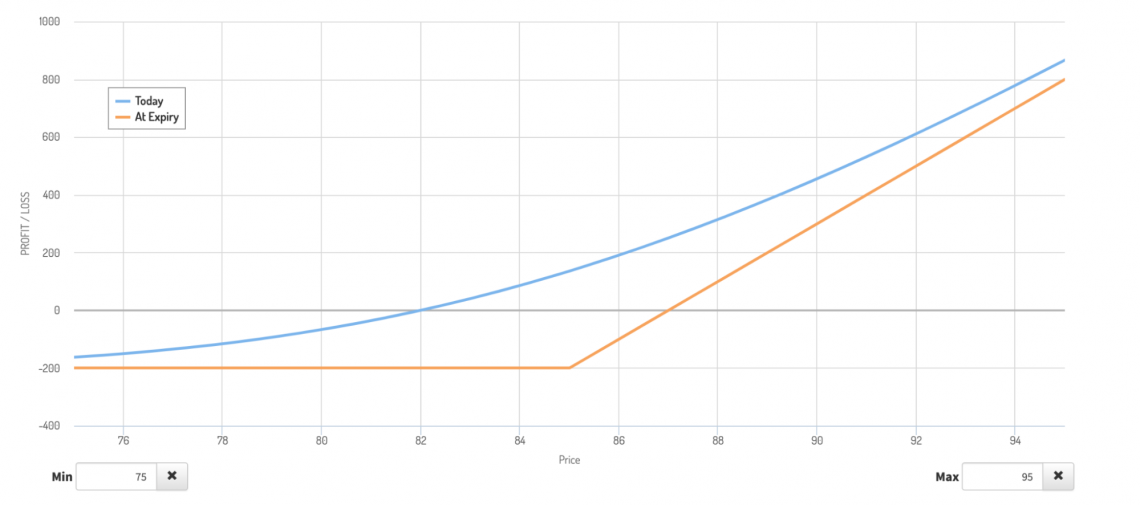

Let’s look at an example of a call option expiring in 30 days for company XYZ. The current price of company XYZ is $82. The strike price is $85. So the premium is $2.

Looking at the profit and loss chart, it becomes clear exactly what the contract is worth at expiration. However, it is also worth noting that there is a difference between the value today and at the end, as the time until expiration gives the contract value because the price can still move.

Let us say, at expiration, the price is still $82. Therefore, we do not exercise the contract because it allows us to buy at $85, which is worthless since the price is below $85, leaving us with a $200 loss from paying the premium to purchase the contract.

Now, let's say, at expiration, the price rises to $86. Because the option allows us to purchase 100 shares at $85, it is exercised. Those shares can immediately be sold for $86. We earn $100 from selling those shares but are still at a $100 loss when subtracting the premium.

Now, let's say, at expiration, the price rises to $90. The contract is exercised. We sell the shares we purchased for $85 for $90. It earns $500. Subtracting the premium, we profit $300.

As we can see from these different scenarios, we are only profitable if the price rises above the strike price by more than the premium. In this case, we need the price to hit $87 ($85 + $2).

Buying a call has the potential for unlimited gains as long as the price of the underlying rises above the strike price. The losses are capped at the amount the investor paid for the contract.

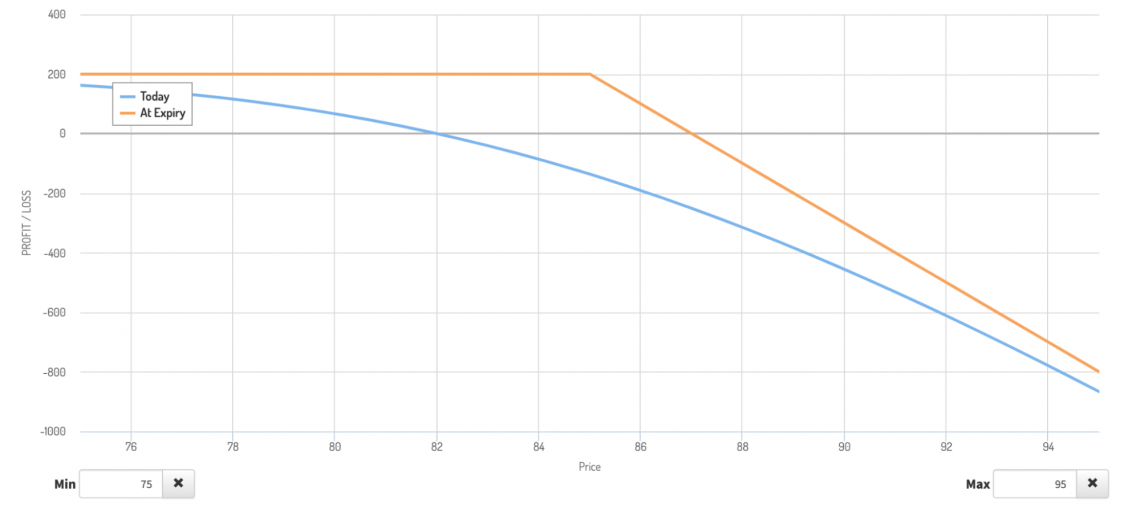

Selling a Call

Selling a call contract is the opposite side of the same trade. The seller assumes the risk of fulfilling the contract and is obligated to sell 100 shares at the strike price if the option is exercised. The seller, therefore, is expecting the share price not to reach the strike.

Using the same call option example, we see that the profit and loss chart is reflected over the x-axis.

Because, in the beginning, the contract is sold, and the premium is collected rather than spent. It is the max profit for the seller of the contract. If the price moves significantly, the seller can be left with a significant loss, as they fulfill the obligation to the buyer of the contract.

Once the buyer breaks even, the seller has zero profit. From any point onward, the buyer's profit equals the seller's loss.

naked call option vs. other Strategies

As briefly mentioned, a naked call option is a strategy for investors expecting the underlying security price to decrease. The primary difference between a naked call and other strategies that involve selling an option is the lack of collateral held by the seller.

We know that it is the seller's responsibility to fulfill the contract's obligations. An exercised call option means selling the shares at the strike price. Therefore, the collateral for a call option is the 100 shares that would be transferred to the buyer.

We will compare the naked call to the covered call and the long put. Because the covered call involves selling the same contract as a naked call and the long put has the same directional bet as selling a call without holding any collateral.

In a way, the long put is more comparable to selling a naked call than the covered call because the investor has the exact expectations when using a long put and selling a call.

Naked vs. Covered Call

For an investor looking to collect the premium of selling a call option without unprotected risk, a strategy such as the covered call could be used. In this case, 100 shares of the underlying would be held.

If the price rises, the investor’s profit increases up until the strike price, where it flatlines. It is because, above the strike, the option is exercised, and the seller of the contract must sell their shares.

If the price of the underlying decreases, then the option contract will not be exercised. However, because the contract seller owns the shares, they have an unrealized loss from the shares declining in value.

If we compare a covered call to a naked call, we see that the investor sentiment is quite different. Because of the value change in the shares held by the contract seller, this strategy would not be used when the investor is bearish on the underlying.

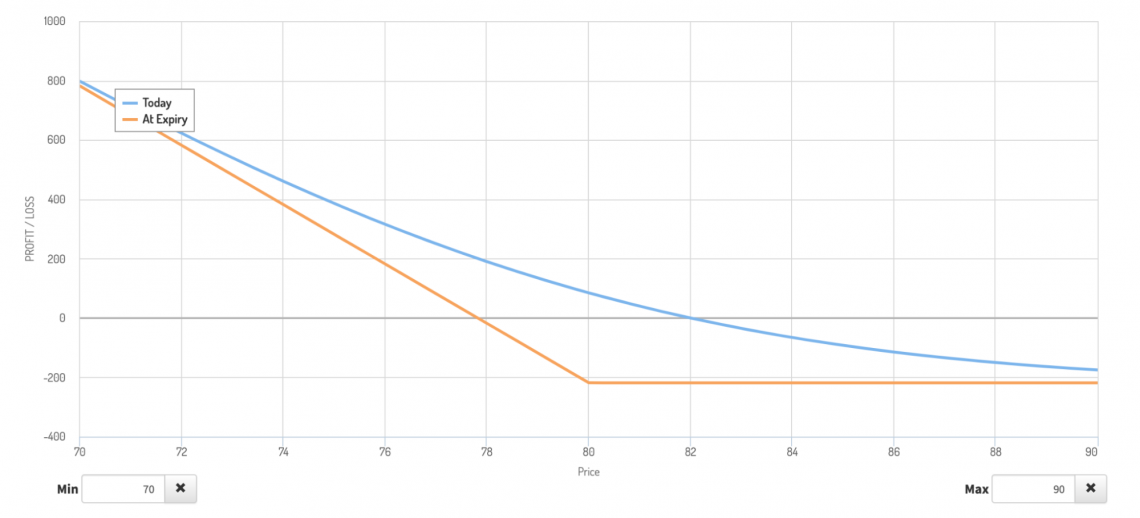

Naked Call vs. Long Put

Buying a put option is a better comparison to the naked call in terms of investor expectation. A put option allows the buyer to sell at a specific price. The expectation is that the share price at expiration is below the strike, which is also a bearish strategy.

Revisiting company XYZ, an investor can pay $218 for a put option that also expires in 30 days at the $80 strike.

There is an opportunity for significant profit as long as the price declines past $76.82 until it reaches zero.

Much like buying a call, for the purchaser of the put, the underlying must move beyond the strike price by the amount of the premium to break even.

In this example, the price must drop below $76 to make as much profit as simply selling the $85 call we described earlier, assuming it expires from the money.

Using Naked Calls

The utility of a naked call becomes evident in the scope of comparisons to the covered call and buying a put.

Unlike its less risky “covered” version, selling a call without collateral allows investors to collect a premium without locking up capital in 100 shares of the underlying stock (covered call example).

Furthermore, compared to its covered counterpart, an unprotected call allows the investor to make a bearish bet on the underlying. As we saw with the covered call profit and loss graph, changes in the underlying asset price affect the profit and loss of the entire trade.

As a result, using a covered call strategy to collect premiums and generate income is only plausible when the investor has a bullish outlook rather than a bearish one.

Compared to other bearish strategies, such as the long put, the investor can collect a premium immediately rather than pay a premium to make a bet on price movement.

When selling a naked call, the trade will be profitable if the underlying does not move far enough above the strike (by the premium, to be exact).

When buying a put, the investor needs the price to move by the amount of the premium past the strike price to break even.

When comparing the two, it is pretty clear that selling a call without coverage is much more likely to be profitable than buying a put.

Investors should also be warned! This difference in profitability around the strike price can be reconciled by the potential for massive gains in the case of buying a put and the potential for huge losses in the case of selling a naked call.

For this reason, a naked call is much riskier for an investor than buying a put if the investor is bearish on the underlying. Investors must decide if this increased risk is within their preferences for overall portfolio risk.

Researched and Authored by Jacob Rounds | LinkedIn

Free Resources

To continue learning and advancing your career, check out these additional helpful WSO resources:

or Want to Sign up with your social account?