K-Percent Rule

A guideline for monetary policy that mandates central banks to raise the money supply regardless of the state of the economy

What is the K-Percent Rule?

The K-percent rule is a guideline for monetary policy that mandates central banks to raise the money supply regardless of the state of the economy. Milton Friedman, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, proposed the rule.

Friedman suggested that, for long-term inflation management, central banks should increase the amount of money in circulation by a specific percentage (the "k" variable) each year.

According to the rule, the money supply should increase at a pace equal to real gross domestic product (GDP) growth. The average real GDP growth rate is between 1 and 4 percent.

In their book “A Monetary History of the United States,” Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz linked inflation to an excess money supply produced by a central bank.

They claimed that deflationary spirals resulted from a central bank's inability to maintain the money supply in the face of a liquidity crisis.

Under this rule, well-established macroeconomic and financial parameters would determine the money supply.

Friedman, in his book, asserted, "the stock of money [should be] increased at a fixed rate year-in and year-out without any variation in the rate of increase to meet cyclical needs.”

According to him, the central bank should adopt an acyclical monetary policy and increase the money supply at a constant pace equal to the real GDP growth rate.

He thought allowing governments any latitude in determining money growth would cause inflation.

Key Takeaways

-

According to the K-percent rule, central banks should raise the amount of money in the economy by a set amount, regardless of how the economy is doing.

-

The rule states that, for long-term inflation management, central banks should increase the amount of money in circulation by a specific amount ("k" variable).

-

Because the rule forbids central banks from interfering, it is modified by many policymakers and economists who use it as a starting point to create other rules that govern monetary policy.

-

A central bank's main goal is to maintain economic stability while keeping an eye on growth rates to ensure the economy isn't expanding too quickly or too slowly.

-

Central banks use the rule to shield the economy against deflation and inflation.

-

The rule gives Fed policymakers little leniency when deciding on monetary policy.

-

Furthermore, the rule is a no-feedback rule and is ineffective in the near term since it forbids any adjustments to monetary policies to reflect changing economic conditions.

How the K-Percent Rule Works

A central bank's main goal is to maintain economic stability while keeping an eye on growth rates to make sure the economy isn't expanding too quickly or too slowly.

Central banks use the K-percent rule to shield the economy against deflation and inflation.

By setting the growth rate of the money supply higher than what is necessary by the rule, the central bank suggests that the circulation of money in the economy is increasing more than the economy’s value.

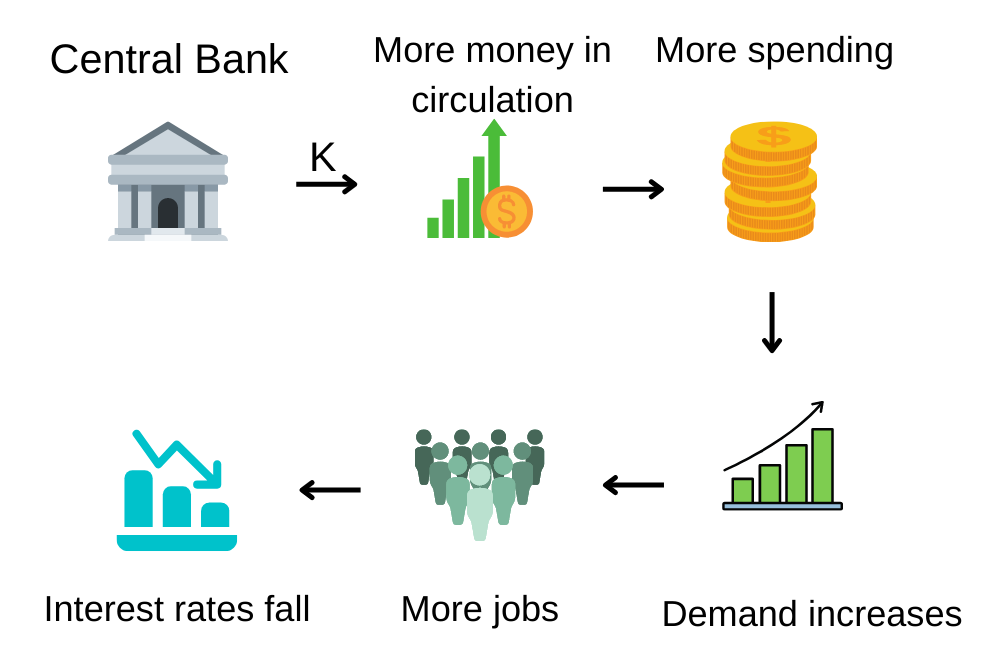

For example, central banks use different monetary policies, such as decreasing the interest rate. This leads to consumers borrowing more money, thereby increasing the money supply.

In contrast, central banks restrict the money supply growth in a booming economy since inflation, in particular, is a byproduct of rapid economic growth. The economy’s growth will slow as a result.

According to Freidman, the annual growth rate of the money supply should be between 3 percent and 5 percent. The rule gives Fed policymakers little leniency when deciding on monetary policy.

Given that discretionary policy could result in errors and exaggerated monetary reactions to economic situations, Friedman thought that monetary policy would be more successful under a rules-based framework.

Many policymakers and economists modify the rule and use it as a foundation to construct other principles used to shape monetary policies. This happens because the rule forbids central banks from interfering.

Furthermore, the K-percent rule is a no-feedback rule and is ineffective in the near term since it forbids any adjustments to monetary policies to reflect changing economic conditions.

For example, the rule has been modified by Joachim Scheide, Chairman of the Forecasting Center at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy in Germany, to make it more practical.

To create a more accurate model, he adds three new variables: "nominal domestic demand," "central bank money," and "error term with the standard features."

Discretionary Monetary Policy

Monetary policy is what controls the money supply and interest rates. It is a demand-side strategy that central banks have established and that governments in various nations use to encourage stability, growth, low unemployment, and stable pricing.

Central banks use tools like:

-

Bank rate policy

-

Credit control policy

Monetary policy can be of two types, expansionary or contractionary:

-

Expansionary monetary policy causes a fall in interest rates and an increase in the money supply.

-

Contractionary monetary policy results in a drop in the money supply and an increase in interest rates.

Milton Friedman won the Nobel Prize in economics and founded monetarism. Monetarism is a school of thought that identifies monetary growth and related policies as the primary source of future inflation.

The Fed implemented several initiatives to restore economic development during the 2007–2008 financial crisis, including lowering interest rates to almost zero and starting a program to purchase U.S. Treasuries and other securities.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, the rules vs. discretion debate dominated monetary policy discussions, and there is still no consensus on which is preferable. Some economists, such as John B. Taylor, are more likely to use rules than discretion.

However, Friedman's K-percent rule forbids central banks from interfering in the formulation of monetary policy. This is because Friedman thought such discretion would be counterproductive and may boost inflation levels.

The rule advocates for rigorous adherence to the suggested norm and does not permit any latitude in formulating monetary policies. Due to this, Friedman's K-percent rule has come under criticism from numerous economists.

In the paper “Model Uncertainty and Delegation: A Case for Friedman's k-Percent Money Growth Rule?”, the authors Juha Kilponen and Kai Leitemo write-

“Many central banks, with perhaps the prominent exception of the European Central Bank, have abandoned regimes of targeting variables such as money growth or the exchange rate.

Accordingly, inflation-targeting central banks put many resources into understanding the link between monetary policy instruments and inflation to establish what information is relevant and how to use this information most efficiently.”

Due to the unknown size and timing of the economy's response to policy stimulus, Friedman questions the value of state-contingent norms in monetary policy.

It is generally accepted that focusing on money growth will keep inflation at or near a constant level, assuming that steady-state output growth and steady-state velocity growth remain constant.

The rule will, however, often diverge from the best course of action determined by minimizing the effect of pricing inertia on economic welfare in a situation where the economy is fully understood.

In his book, Friedman argued that the Great Depression in the United States in the 1930s was mostly brought on by the Federal Reserve's weak monetary policy.

K-Percent Rule Criticism

Despite monetarism's rise to prominence in the 1970s, Keynesianism, the school of thought it aimed to replace, criticized it.

The great British economist John Maynard Keynes served as an inspiration to the Keynesians, who hold that demand for goods and services is the key to economic output.

They argue that because velocity is intrinsically unstable, monetarism falls short as a theory of the economy. They give little to no weight to the quantity theory of money and the need for rules made by monetarists.

They contend that making the Fed a slave to a set money target is risky because the economy is prone to significant swings and irregular instability. Instead, they argue that the Fed should have discretion or latitude in deciding how to implement policy.

Keynesians do not think that markets swiftly revert to a level of output consistent with full employment after adjusting to disturbances.

For the first quarter century following World War II, Keynesianism was dominant.

The 1970s, however, a decade marked by high and growing inflation and sluggish economic growth, saw a strengthening of the monetarist challenge to the conventional Keynesian theory.

Keynesian theory lacked suitable policy solutions, while Friedman and other monetarists made a compelling case that rapid growth in the money supply was to blame for the high inflation rates, taking control of the money supply the essence of sound policy.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?