Derivatives

Financial instruments that derive value from an underlying asset, asset group, or benchmark.

What Are Derivatives?

The word derivative simply means something is related to or based on another thing. In finance terms, derivatives are financial instruments that derive value from an underlying asset, asset group, or benchmark.

Because a derivative's value depends on the underlying asset, there is a very high degree of correlation between the price movement of a derivative and its underlying.

While many derivatives are leveraged, it is essential to note that not all derivatives operate with increased leverage.

Not only does this mean increased volatility, but risk assumption with increased leverage implies additional costs that influence the derivative's price changes, irrespective of the underlying price movement.

These can derive value from all sorts of assets. Common examples include the following:

- Equities and Equity Indices

- Bonds

- Currencies

- Commodities

- Interest Rates

Key Takeaways

- Derivatives are financial instruments that derive their value from an underlying asset, asset group, or benchmark. Common types include Options, Futures, Forwards, and Swaps.

- Derivatives can be linked to various assets like equities, bonds, currencies, commodities, and interest rates. Their value is highly correlated with the price movement of the underlying asset, introducing both volatility and risk.

- Options are derivative contracts allowing speculation on security prices. Call options provide the right to buy, while put options allow selling. Critical components include the strike price, expiration date, and premium.

- Futures involve exchanging underlying securities in the future. Key concepts include contract size, tick size, contract value, and delivery specifications.

- Forwards are private agreements, unlike futures, traded over the counter. They lack standardized specifications, making them riskier due to higher default possibilities.

- Swaps involve trading cash flows over a specified period. Common types include interest rate and currency swaps, facilitating risk hedging and comparative advantage.

Types of Derivatives

From these underlying assets, many types of derivative contracts can be created.

Of these, the most common are the following:

- Options

- Futures

- Forwards

- Swaps

Why would an investor purchase an asset that derives its value from an underlying asset rather than just the asset? As was briefly mentioned, derivatives are typically leveraged. This allows investors to both hedge risk and engage in speculation using derivatives.

Where are these traded? In the derivatives market, multiple parties participate, with one party assuming the risk while another seeks increased leverage by paying for the derivative contract. These contracts are traded over the counter (OTC) or on an exchange.

For OTC derivatives, there is a higher degree of counterparty risk. Counterparty risk is simply the risk that one of the parties involved in the contract defaults on their obligation.

Options

Options are a type of financial instrument used to speculate on the price of a security. As a derivative contract, its value is determined by changes in the underlying security price.

We see options, contracts, calls, and puts in the following window. The call options are highlighted on the left below:

An equity call option grants the owner the right to buy 100 shares of the underlying for a specified price, but it is not an obligation, and this right can be exercised before the contract's expiration date. Put options instead, giving the right to sell those 100 shares.

While there are many reasons that a stock option may change its value, only a few basic components are needed to understand options and their applications:

- Strike Price

- Expiration Date

- Premium

Example

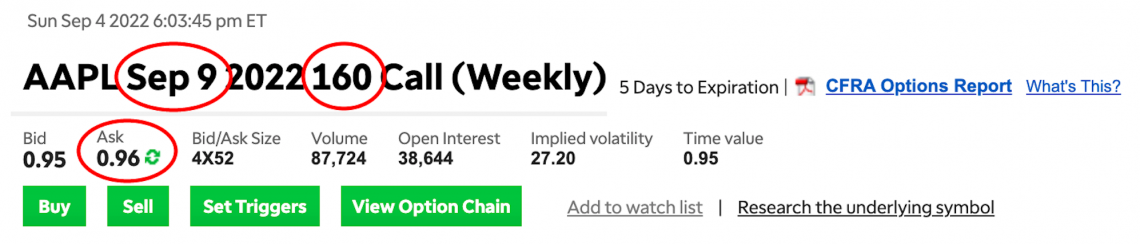

For this AAPL weekly call expiring September 9, 2022, buyers pay a premium of $0.96, also known as the ask.

An option contract strike determines what is known as "moneyness." An in-the-money contract is one where the underlying price is above the strike for call options. Conversely, a price below the strike would mean the option is out-of-the-money.

For put options, the moneyness and strike price relationship is the opposite. A price above the strike means the contract is out of the money, while a price below the strike means the contract is in the money.

For American options, the expiration date is the last date an option contract can be exercised, although they are sometimes exercised before. European options can only be exercised on their expiration date.

There is no benefit to exercising an out-of-the-money contract. For this reason, contracts are typically only exercised when in the money.

Even with American options, early exercising is not common. Instead, investors tend to exit their position by selling the option contract to another investor. In cases where the investor originally went short, they repurchase the option contract sold.

An option contract premium is the price of purchasing the options and what the seller collects. The premium is expressed as a price per share on the contract, and the total contract price is the premium multiplied by 100 shares:

Contract Price = Premium x 100 shares

Investors only need to pay the premium rather than the price of 100 shares. Because the contract represents 100 shares, the investor needs to remember that the underlying asset's movement influences its price, and it can change rapidly, particularly as the option approaches its expiration date.

Note

A simple way of understanding premium is considering the price an investor is willing to pay to have the temporary leverage an option contract offers.

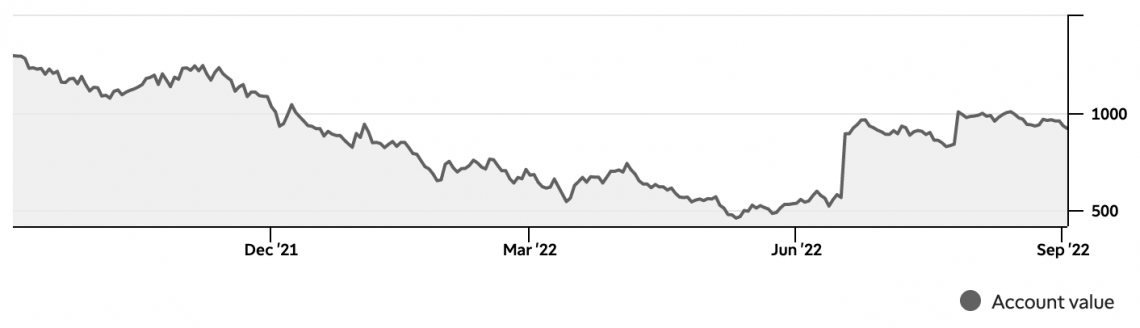

Therefore, if the investor's portfolio contains many options, it will likely be volatile.

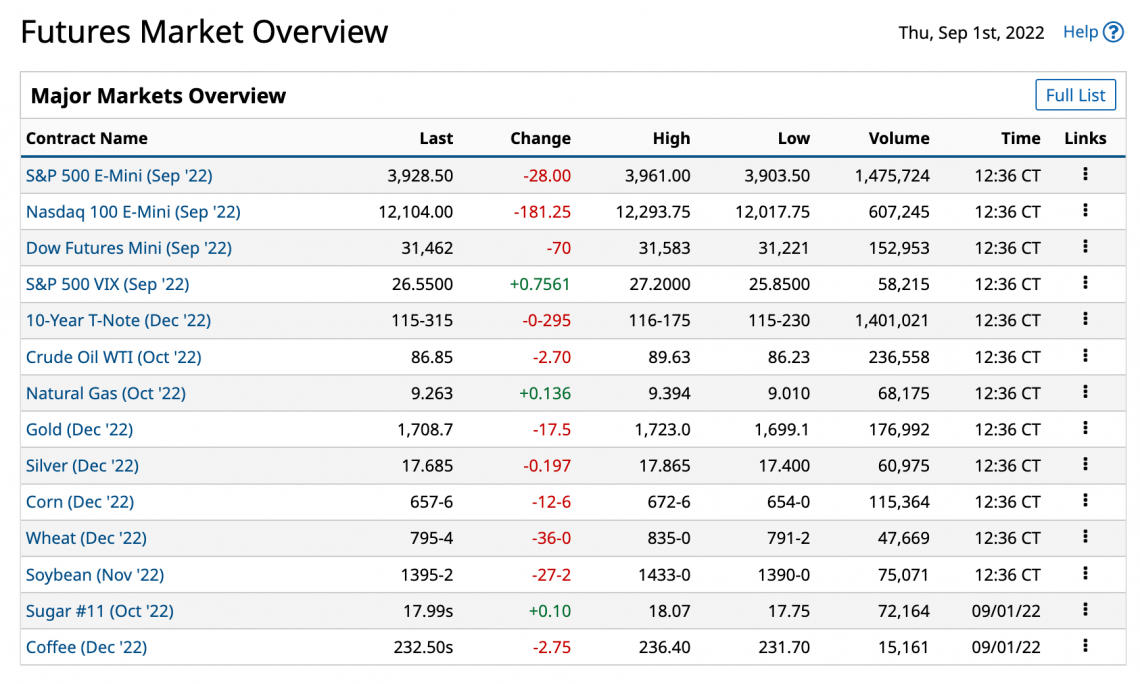

Futures

Like options, futures contracts focus on exchanging underlying security at some time in the future. However, unlike an options contract, which gives the buyer the right to exercise, futures contract buyers must purchase the underlying contract at the set date.

A futures contract includes several components:

- Trading hours

- Contract size

- Tick size

- Contract value, otherwise known as notional value

- Delivery specifications

Each futures contract has trading hours depending on the commodity or financial instrument.

Futures Trading Concepts

Futures trading has different concepts that we need to understand.

- Contract Size: Contract size represents how much of the underlying asset the futures contract controls. For example, oil futures are always standardized at 1,000 barrels.

- Tick Size: The tick size is the smallest change that can be recorded in contract value. For example, oil changes are quoted in cents, and one tick movement would be $10, determined by the minimum price fluctuation, regardless of the contract size.

- Contract Value: The contract value is how much the contract is worth and can be calculated by multiplying the contract size by the current market price.

- Delivery: Delivery specifies how the contract is settled, financially or physically. Both institutional and retail investors may opt for physical or financial settlement based on their goals and strategies. For contracts that are typically physically settled, investors must close the position to avoid product delivery.

Example

Like option contracts, futures can hedge risk or speculate on the direction of future price movements. Let's take a look at an example using wheat.

The wheat futures contract sellers would be the farmers, whereas the buyers are bread manufacturers who will continue to need wheat in the future.

To hedge risk, bread manufacturers lock in a price that would benefit if prices increase. Losses on the contract from decreasing prices are offset by cheaper commodity purchases at the spot price.

Farmers are also hedging risk in this situation. If prices rise, their losses on the contract are offset by other high-priced wheat sales. Decreasing wheat prices is less damaging, as they are locked into valuable agreements to sell wheat for higher prices via futures contracts.

Forwards

Forwards contracts work differently from futures contracts. While futures contracts trade in exchanges, forwarded contracts are typically private agreements between buyers and sellers and rarely trade.

In terms of structure, forward contracts work quite similarly to futures contracts. The key difference lies in the negotiated specifications between parties, such as the absence of a specified contract size.

As a result, forward contracts are said to be over-the-counter (OTC) instruments. The lack of exchange makes the default risk of these contracts much higher than that of futures contracts.

Example

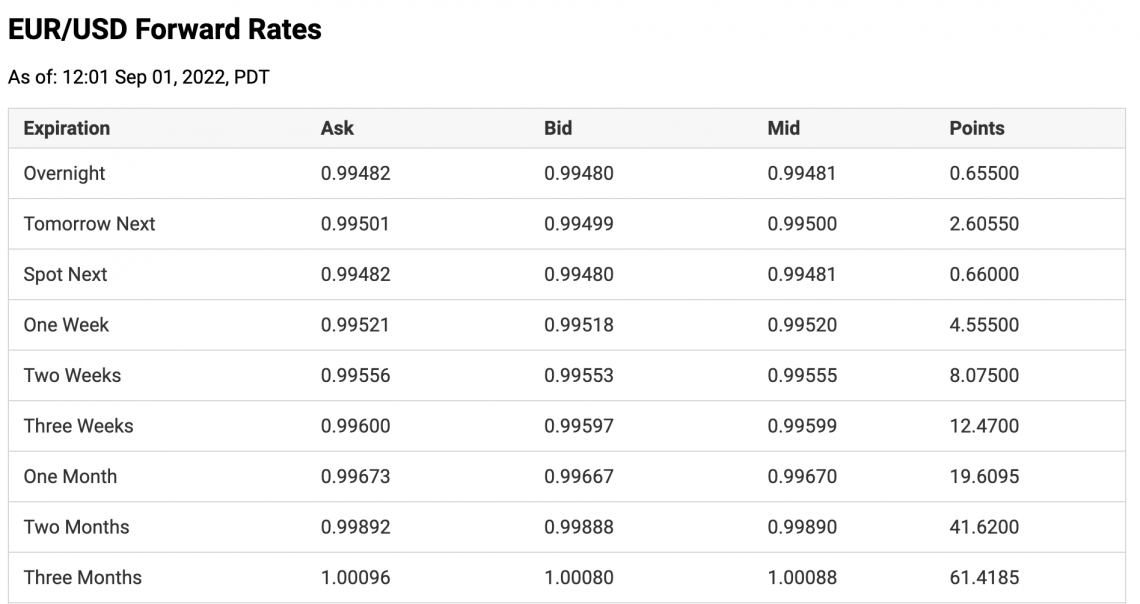

A relatively easy-to-follow example of a futures contract is an exchange rate quote. This can be used by manufacturers who buy parts from foreign factories. To purchase these components, they must first purchase the foreign currency.

Note

In this example, the forward contract is being used to hedge risk.

If the foreign currency strengthened relative to the domestic currency, purchasing foreign goods would be more expensive.

Because the manufacturer would rather not assume the risk of increased prices, they enter into a forward contract. However, the manufacturer is foregoing the opportunity to benefit from an exchange rate shift by doing so.

In addition to being used as a risk-hedging tool, forwards can also be used to speculate. If the purchase of a forex forward contract locks in an exchange rate, they could profit from the price difference in exchange rates if the rates shift in a beneficial direction.

For example, an investor is quoted the forward rate at which currency A can be traded for 2 units of currency B. After one year, when the transaction is settled, currencies A and B are at parity, meaning that 1 unit of currency A can be exchanged for 1 unit of currency B.

Using the forward exchange rate agreed upon previously, the investor can double their domestic currency, in this example A. Then, they exchange the agreed-upon amount for currency B and immediately repurchase currency A at the spot exchange rate.

Swaps

Swaps are agreements between two parties where cash flows are traded for a specified period. As such, they are also considered OTC derivatives. The most common examples of swaps track interest rates and currencies.

Typically, swaps involve one fixed interest payment and one variable payment. The corresponding sequence of cash flows is exchanged between the two parties for the agreed-upon period. During this period, the two parties exchange cash flows at agreed-upon settlement dates.

Example

A hypothetical example of what is known as a plain vanilla interest rate swap would be the following:

- Company A agrees to pay 3% interest to Company B on a notional amount of 10 million

- Company B agrees to pay the current Federal Funds Rate (FFR) +1% to Company A in a notional amount of 10 million

If, at the end of the year, the FFR is 2.25%, company B will be liable for $325,000 to company A. With the $300,000 payment that Company A agreed to pay Company B, Company A nets $25,000.

Swaps like this serve two main purposes: commercial needs and comparative advantage.

The above example would match up well with the commercial needs side. For instance, if company A were a bank, the floating interest payments would be beneficial. This is because bank account deposit liabilities are variable rates, whereas their extended loans are fixed.

By entering a swap, the bank can have some variable rate income that matches up more closely with their outstanding liabilities; hence, it satisfies their commercial needs.

Note

On the comparative advantage side, currency-based swaps would be more relevant. For example, a favorable swap could be agreed upon if one American company was looking to expand into Europe and a European company was looking to expand into the United States.

Both companies need foreign currency but would likely find better financing terms domestically. By creating a swap, both companies can discover more advantageous rates for foreign currency.

Advantages Of Derivatives

Now, let us look at some of the different advantages of derivatives below:

- Price Stabilization: One of the primary advantages of derivatives lies in their ability to lock in prices. This feature enables businesses and investors to secure a predetermined price for an asset or commodity, providing a degree of stability in uncertain market conditions.

- Risk Mitigation: Derivatives offer a valuable tool for hedging against unfavorable market movements. Investors can use them strategically to offset potential losses and safeguard their portfolios from unforeseen risks, fostering a sense of financial security.

- Leverage Opportunities: The capability to purchase derivatives on margin adds an extra layer of appeal. By utilizing borrowed funds, traders can amplify their market exposure. While this can enhance potential returns, it's essential to acknowledge that leverage also amplifies the risk, making losses more pronounced.

- Portfolio Diversification: Incorporating derivatives into investment strategies allows diversification, spreading risk across different assets. This diversification can be a key element in managing overall portfolio risk and enhancing long-term financial stability.

Disadvantages Of Derivatives

On the other hand, the cons are:

- Valuation Challenges: The inherent difficulty in valuing derivatives stems from their dependence on the price of an underlying asset. This complexity makes it challenging to precisely determine the true value of a derivative, leading to uncertainties in assessing investment positions.

- Counterparty Risks: Over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives introduce a layer of risk related to counterparty default. Predicting or quantifying these risks can be elusive, posing potential threats to investors involved in such transactions.

- Complexity: Derivatives, by nature, are intricate financial instruments. Understanding their mechanisms and evaluating the associated risks demand a level of financial acumen that may be beyond the grasp of some investors. This complexity adds a layer of challenge to the widespread comprehension and usage of derivatives.

- Vulnerability to Market Sentiment: Derivatives lack intrinsic value; their worth is solely derived from the underlying asset. This makes them susceptible to fluctuations driven by market sentiment and demand factors. Consequently, the price and liquidity of derivatives can be influenced independently of the underlying asset's market dynamics.

Conclusion

Many financial instruments derive value from other things. In the world of finance, these securities are known as derivatives.

Common examples of derivatives include options, futures, forwards, and swaps. These contracts can track equities and equity indices, bonds and other fixed-income instruments, currencies, commodities, and even interest rates.

These advantages enable investors to hedge risk and speculate on the underlying with smaller amounts of capital than what would be required to control the same amount.

Due to the higher leverage, these contracts exhibit increased volatility. While volatility is a risk, derivatives also have counterparty risk, further adding to the unpredictability of returns.

For these reasons, it is recommended that investors looking to incorporate derivatives into their investment strategy have a strong understanding of the contracts themselves and anything that could affect the underlying asset.

For equity-based contracts, such as options, fundamental stock analysis is required to develop a more sophisticated strategy than relying on chance.

Other types of derivative contracts should be approached with care. For instance, understanding macroeconomics is recommended for interest rate-based contracts and fixed-income valuation for bond-based derivatives.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?