Economies of Scope

Occurs when a firm expands the variety of its production, achieving savings due to the production of preexisting products/services.

What are Economies of Scope?

“Economies of scope” is an economic concept that occurs when a firm expands the variety of its production, achieving savings due to the production of preexisting products/services.

In other words, it occurs when it's cheaper for a single firm to produce two different products than it is for two firms to each produce one.

Economies of scope are not about producing the same goods at a lower average cost (economies of scale) but using a firm's size and resources to produce similar or related goods. When a firm diversifies its product lines, it achieves many goals:

- Meets consumer preferences and wants

- Increase profits due to decreasing total cost (a direct result of diversifying its product lines)

- Achieves efficiency by producing a wider range of products at a lower cost and, as a result, the firm's total revenue will increase (revenues will outweigh the cost, so the profits will increase)

Example of Economies of Scope

Suppose there’s a bakery that produces bread. The manager decided to exploit its product line by producing a wide range of products like donuts, cakes, cookies, etc.

We can conclude that the firm exploited economies of scope by increasing the variety of products it produce, and, as a direct result, the bakery’s total costs will decrease.

With this increase in the breadth of goods the bakery produces, it can now also meet the needs of more consumers.

Some other examples: Tesco, the British chain store: Tesco's capability in warehousing and distribution gives it a cost advantage across many geographic markets.

Many successful businesses around the world exploited these factors:

- A great example is Starbucks. Starbucks is famous for producing coffee to meet consumer needs, but Starbucks diversified its line by producing a wider range of products like donuts, cookies, cakes, and salads. This diversification realized millions of dollars in profit for Starbucks.

- Another example is Apple. Initially, Apple produced only the iPod, which later extended to phones (iPhone). It also produced tablet computers (iPad) and, later, smartwatches (Apple Watch) and Laptops (Macbook).

This exploited economies of scope as, for example, the iPhone and iPad need the same type of screen.

Learning economies refer to reductions in unit costs due to accumulating experience over time. Its experience in producing iPhones let Apple expand the variety of products it produces.

Formula for Economies of Scope

Let total cost (TC) denote the cost for a firm to produce good X and good Y. Assuming this, a production process exhibits scope economies if:

TC(Qx, Qy) < TC(Qx, 0) + TC(0, Qy)

- This formula captures the idea that it is cheaper for a single firm to produce both goods X and Y than for one firm to produce X and another Y.

- Note that a firm’s total costs are zero if it produces none of either product, so TC(0, 0) = 0.

Application

Suppose a firm produces shirts and pants; let’s denote shirts by X and pants by Y.

The firm will exploit economies of scope if:

TC(Qx, Qy) < TC(Qx, 0) + TC(0, Qy)

In other words, the total cost of producing both shirts and pants is less than the total cost of producing shirts and pants alone.

So, the firm is producing more, increasing sales, meeting consumer needs, and realizing economic profits. Moreover, we can measure the degree of economies of scope using the formula below:

DSC = [TC(q1) + TC(q2) - TC(q1,q2)]/ TC(q1,q2)]

- If DSC is greater than zero, there are economies of scope

- If DSC is equal to zero, economies of scale and economies of scope are absent

- If DSC is less than zero, the firms face diseconomies of scope

Economies of Scope vs. Economies of Scale

Economies of Scale and Scope are two distinct concepts, even though they seem similar.

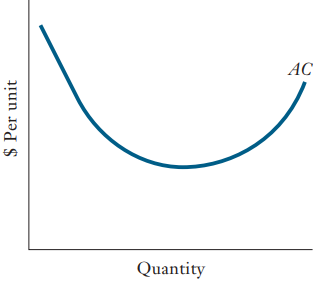

The production process for a specific good or service exhibits economies of scale over a range of output when the average cost (i.e., cost per unit of output) declines over that range.

If the average cost (AC) declines as output increases, the marginal cost of the last unit produced (MC) must be less than the average cost.

A firm’s average costs may initially decline as it spreads fixed costs over increasing output. Fixed costs are insensitive to volume; they must be expended regardless of the total output.

The two economies allow firms to reduce costs. However, economies of scale occur because the firm increases the production of one good or service the firm offers, while economies of scope occur due to increasing the variety of goods and services the firm offers.

Usually, firms exploit economies of scale and scope, as well as learning economies, to produce more at a cheaper rate.

Suppose a firm is producing 1000 pieces of steel; it decided to increase production to 1500, and, as a result, total cost decreased, meaning the firm exploited economies of scale.

Economies of scale can be reflected in a graph. It is represented by a decreasing average cost curve (U-shaped average cost chart).

There are many sources of the economies of scope, including economies of density, purchasing, advertising, physical properties of products, and inventories.

It is important to note that there are also multiple types of scope savings:

- External

- Internal

- Purchasing

- Technical

- Financial

Diseconomies of scale are the opposite. This is when the average cost of production increases the more units are produced. This occurs because the marginal cost is above the average total cost.

Diseconomies of scale worsen the situation of the firm as the firm increases production and marginal cost increases.

The graph above shows how, initially, average cost decreases as we increase Q (quantity produced). This demonstrates economies of scale.

However, further along, we see that average costs rise with the quantity produced. This is the effect of diseconomies of scale.

Different Ways to Achieve Economies of Scope

The sources of expanding the production are:

1. Advertising Reach and Umbrella Branding

Suppose there are two firms in a market. Which firm will have more power or advantage? The larger one will have an advantage over the other (i.e., one has many more stores across the country than the other).

Suppose the two decided to advertise their new products. The products are different from each other, but they’re being advertised on the same channel for the number of viewers.

Despite these similarities, the cost per effective message is much lower for the larger firm than the smaller one because, the larger firm has many more, meaning more customers.

To calculate the advertising cost per consumer of a product, we use the formula below:

Cost of sending a message ÷ Number of actual consumers as a result of the message

From the formula above, we can conclude that larger firms enjoy lower advertising costs than smaller ones. Firms can also exploit umbrella branding, especially if they introduce a product under a single brand name.

For example, Apple, when it introduced Apple Watches, loyal Apple consumers bought them because they knew that everything Apple produces is widely accepted and provided a certain status.

However, exploitation of a brand name is not risk-free. If the new product is unsatisfactory, customer dissatisfaction may harm the image of existing and future products.

2. Research and Development (R&D)

Research and development expenditure exceeds 10% of revenues at many companies. The nature of engineering and scientific research indicates that there is a minimum feasible size for an R&D project, as well as a department.

For example, drug companies spend an enormous amount of money on developing, testing, and getting approval for a single drug.

A firm can reduce the impact of these costs by increasing production/sales. Ideas from one project can help another project, ultimately achieving savings due to scope.

Economies of Scope Advantages

Firms can take advantage of economies of scope to react to any changes in consumer tastes and preferences. This is especially important today, where everything changes at an exponential speed due to advancing technology.

For example, in the digital era, mechanical cameras became useless. They became outdated, and firms that continued to produce mechanical cameras only experienced huge losses due to a large decrease in sales.

However, firms that shifted to producing, for example, digital cameras, saw a huge rise in sales. So, these firms only recovered losses after diversifying their production to include digital cameras, meeting consumer needs and want.

Artificial Intelligence and automation can do nearly anything that humans can at a cheaper, faster rate, and, unlike us humans, their capabilities are growing at an exponential rate.

Digitization fosters economies of scope with robots and advanced machines because firms can easily expand their production line with no need to hire more workers. This leads to more production, more sales, and fewer costs.

Diversification reduces risks firms could face.

For example, there is a company producing one type of fossil-fuel vehicle. Suppose, suddenly, there’s an oil crisis and the prices of fuel soar, causing people to switch to other types of cars like hybrid, solar, and electric cars that use no or less fuel.

The production process of a particular good or service represents economies of scale at a particular production volume when the average cost (the cost per unit of production) decreases as production increases (or increases as production decreases).

If the average cost (AC) decreases as output increases, the marginal cost of the last produced unit (MC) must be lower than the average cost.

A company’s costs may initially fall as it distributes fixed costs among its units. Fixed costs do not depend on quantity. They are consumed regardless of overall performance.

Economies of Scope Disadvantages

Firms may have little or no knowledge of how to produce, market, sell, etc., new products. Suppose a bakery that produces bread now decides to produce donuts.

The firm will produce donuts, but not at the same level as a firm that specializes in donuts. Moreover, the sale of new products may come at the expense of the original product that the firm usually sells, bread.

Firms may also face diseconomies of scale. This is more common when increasing the size of production firms, but why?

An average cost curve captures the relationship between average costs and output. Economists often depict average cost curves as U-shaped.

The production process of a particular good or service displays economies of scale at a particular production volume when the average cost (that is, the cost per unit of production) decreases as production increases and/or vice versa.

If the average cost (AC) decreases as output increases, the marginal cost of the last produced unit (MC) must be lower than the average cost.

The average costs of a company may initially fall as it distributes fixed costs over its produced units. Fixed costs do not depend on quantity. They are consumed regardless of overall performance.

Examples of such quantity-independent costs include manufacturing overhead costs such as insurance, maintenance, and property taxes.

Finally, in the event of capacity bottlenecks, adjustments, or other agency issues, companies can experience an increase in average cost.

We can conclude from the above that if the firm produces too much output, AC will re-increase after decreasing as a result of increasing production.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?