Molodovsky Effect

It states that the P/E ratio rises due to earnings decreasing faster than price.

What is the Molodovsky Effect?

The Molodovsky Effect states that, at low points in the business cycle, the P/E ratio rises due to earnings decreasing faster than price. Conversely, at high points in the business cycle, the P/E ratio lowers due to earnings increasing faster than price.

In 1953 Nicholas Molodovsky published an article titled “A Theory of Price Earnings Ratio” in the Financial Analyst Journal. In this article, he outlined a phenomenon seen in some businesses that go contrary to intuition.

The P/E ratio or price-to-earnings ratio divides the market cap of a company by its earnings or the price per share by earnings per share:

- An increase in the value of a company increases the P/E ratio and vice versa.

- An increase in a company’s earnings decreases the P/E ratio and vice versa.

When considering the P/E ratio and the business cycle, one would assume that rising earnings would lead to an increased price. The assumption is that a price increase would occur due to higher expectations of future cash flows.

Molodovsky argues that price rises slower and sometimes ignores seasonal changes entirely. He states that the P/E ratio lowers since, as mentioned previously, earnings rise.

Now let’s look at the opposite case. Your gut instinct might tell you that decreasing earnings caused by seasonal cycles would lead to a decrease in price. The thinking here is that a decrease in forecasted cash flows would occur, leading to a decrease in the value of the stock.

However, the Molodovsky Effect contradicts this, stating that price decreases slower than earnings, causing a rise in the P/E ratio.

The largest takeaway of the theory is that a low or high P/E ratio on its own is unhelpful because it ignores factors external to a company affecting P/E.

The Molodovsky Effect and P/E Ratios

The P/E ratio is one of the many financial metrics used in a comparable company analysis to evaluate a company.

The numerator of the formula is the market cap, and the denominator is earnings. An alternative form of P/E that renders the same result is the price per share as the numerator and earnings per share as the denominator.

There are two main forms of the P/E ratio, each with its purpose:

- Trailing P/E: Uses earnings from the past 12 months as the denominator

- Forward P/E: Uses earnings forecasts for the next 12 months as the denominator

On the one hand, Trailing P/E is seen as a more dependable ratio as it depends on events that have already occurred. On the other hand, this makes it more effective for a well-established company with fewer growth prospects.

It doesn’t work as well for an early-stage tech company, for example, since these kinds of companies have a large potential for earnings growth.

On the other hand, Future P/E is used when investors believe forecasted results are more important for company pricing than past earnings.

One of the main issues with trailing P/E is a common warning: past performance doesn’t indicate future results.

Future P/E’s issue is its exposure to the risk of biases and errors in forecasting.

The Molodovsky Effect, in theory, works for both types of the P/E ratio. The only time you can’t see its effects is with measurements of past earnings that adjust for the effects of the economy and its cycles.

These ratios should not be used as the Molodovsky Effect focuses on the business cycle results, which these long-term ratios ignore.

When does the Molodovsky Effect apply?

While Molodovsky made no exceptions to his theory, there are still some special cases.

Companies unaffected by the business cycle fluctuations don’t follow the thesis. One example is P&G, a producer of consumer staples like toilet paper and laundry detergent.

In the case of P&G, for example, a recession will affect earnings significantly less than in other sectors. This would lead to reduced or non-existent evidence of the Molodovsky Effect.

Companies affected by economic fluctuations are better candidates for seeing the Molodovsky Effect.

As a recession worsens, consumers cut out frivolous spending, and the retail industry suffers. The retail industry includes companies producing luxury clothing, beauty supply companies, etc.

This leads to decreased earnings and, according to Molodovsky, an increasing P/E ratio. In the case of an upturn, the same changes occur but in the opposite direction.

In practice, analysts rarely cite the Molodovsky Effect as part of an investment strategy. This is due to its non-universal application, making it unreliable.

Further, many advancements in securities trading have been developed since 1953, the release year of the paper.

These advancements have led to larger market participation and better technology. A far more developed market has emerged as a result of these factors. Our current market can predict and account for seasonal changes with greater speed and accuracy.

The Molodovsky Effect, due to these elements, has become a less impactful investment theory.

The Molodovsky Effect in Practice

The COVID-19 pandemic has been the catalyst for a collapse in earnings for some industries.

Hospitality has been seeing these particular effects. This downturn in revenue is common in the hospitality industry during recessions.

This is due to hospitality services, like hotels, restaurants, etc., relying on consumers’ discretionary income, something that reduces during economic downturns.

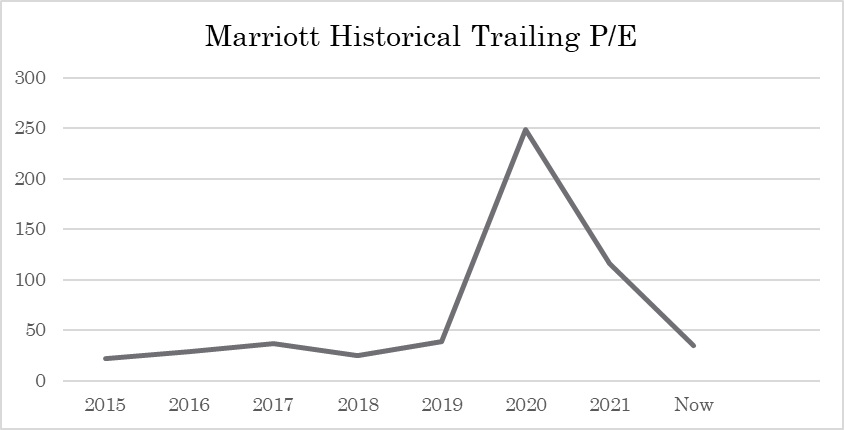

Looking at Mariott International Inc., an international hotel, residential, and timeshare property company, we can see the Molodovsky Effect. Before the pandemic, Marriott had a 5-year P/E average of around 30.

During the pandemic, when Marriott’s earnings suffered, P/E reached almost 250.

In normal circumstances, one might assume that this huge increase in P/E would be due to some new strategy increasing Marriott’s future earnings potential far beyond the present state.

Now, with the Molodovsky Effect, we understand that this sharp spike in P/E is, in reality, due to Marriott’s decrease in earnings.

Price didn’t drop proportionally as investors expected that COVID-19 would only have a temporary effect.

COVID-19 restrictions have continued to reduce, and Marriott’s earnings have risen. So Molodovsky’s thinking held, with Marriott’s current P/E standing at 35, near pre-pandemic levels.

These P/E trends can be seen in the chart above.

For an investor, it may seem that, since there were no particular positive business changes, this high P/E was unjustifiable, making Marriott a nonviable investment.

However, during this same period of astronomical P/E, Marriott stock tripled in value.

During the pandemic, the Molodovsky Effect would’ve been a reasonable way to refute the claim that Marriott stock was an unwise investment due to its astronomical P/E.

Researched and authored by James Fazeli-Sinaki | LinkedIn

Free Resources

To continue learning and advancing your career, check out these additional helpful WSO resources:

or Want to Sign up with your social account?