Discount Bond

Bond that is initially sold for less than its face value or par value.

What Is a Discount Bond?

A discount bond is a bond that is initially sold for less than its face value or par value. The face value of a bond is what the borrower repays at the end of the bond’s maturity. It usually equals $1,000, or a tenth multiple of that number.

A bond is also considered a discount if it is bought and sold in the secondary market at a price below its face value. If a bond is notably sold below its par value, then this bond is known to be a deep-discount bond.

At its issuing, a bond may be sold:

- At its par value, the bond's price is precisely equal to its face value, which is repaid at the end of its maturity.

- At a discount, meaning that the price of the bond is less than its face value, as mentioned.

- At a premium, meaning that the price of the bond is more significant than its par value.

Therefore, a bond premium is the opposite of a bond discount. The former has an initial value higher than par, while the latter has an initial value lower than par. That being said, most bonds that don’t have a long time to maturity are sold at a discount.

For example, a bond with a face value of $1,000 that is sold at $940 is a discount bond. Specifically, the discount is worth $40. Meanwhile, a bond with a face value of $1,000 sold for $1,050 is a premium bond. The premium, in this case, is worth $50.

Note that a bond being a discount bond is only dependent on the price and the face value of the bonds being bought and sold. Bonds sold at a discount or a premium are independent of the yield to maturity, the coupons to be paid, and the time taken for maturity.

When a bond is sold at a discount, the current price or the present value of that bond is lower than the amount of repayment at maturity. This means that the value of the bond will experience appreciation throughout its life. This is known as capital gains yield.

Understanding The Discount Bonds

As mentioned, discount bonds are sold at a price below their par value (usually $1,000). For example, a bond with a face value of $1,000 and is sold for $900 is considered a discount bond with a discount of $100.

Why would a bond be sold at less than its par value? As long as the bondholder earns coupons (interest payments) throughout the bond's life, why would the person pay less than $1,000 to purchase that bond?

The answer is simply that the coupons sometimes aren’t enough to compensate for the idea of lending $1,000 to a bond issuer. Hence, in addition to the coupon payments, the value of the bond itself should appreciate justifying the intention of lending that money in the first place.

Explaining further, suppose the market interest rate is 12%. In other words, the yield to maturity of a $1,000 face value bond is 12%. If the coupon rate is 10%, someone who buys that bond at par value, i.e., at a price of $1,000, is not compensated enough for lending money.

Hence the investor would only be willing to pay the price less than the face value of $1,000 to still have the incentive of lending that money. Without such a discount, no one would have the motivation to buy a bond.

In contrast, if the coupon rate were, for some reason, higher than the current market interest rate for similar bonds, bond issuers would not be incentivized to sell the bonds unless they sell them at a price higher than par, hence establishing a premium bond.

Overview on bonds

The most common way for corporations and governments to borrow money from the public over the long term is by issuing bonds. Bonds are debt securities sold by these companies to the general public in exchange for cash.

Bonds are usually a type of interest-only loan. This means that the principal, the amount borrowed initially, will not be repaid by the issuer until the bond's maturity. The issuer will only make periodic interest payments.

For example, suppose a tech company borrows $1,000 from you in the form of a bond for 25 years. The interest paid on such securities from tech companies is roughly 11 percent annually. This means that the company will pay you $110 annually as interest.

Only at the end of the 15 years, when the bond matures, do you get paid back the $1,000. This is the typical arrangement of most bonds. However, there is a multitude of terms that we should be familiar with surrounding bonds.

Factors related to Bonds

There is a particular set of vocabulary one must know to be able to understand bonds. These terms describe the essential characteristics of bonds, like the amount to be paid back, when the bond matures, etc. The previous example is going to be used to introduce these terms.

1. Maturity

The time to maturity of a bond is the number of years until the par value of the bond is paid. When a corporate bond is initially issued, its maturity is usually 30 years. As time passes after the bond has been issued, fewer years remain until it matures.

In our previous example, the bond's term to maturity was 25 years. This means you will be paid interest every year for 25 years. At the end of the 25 years, you will get paid back the initial amount you lent, which was $1,000.

2. Face value (par value)

A bond’s face value - also referred to as par value - is the sum of money that the lender gets repaid when the bond matures. In our example, the bond had a face value of $1,000. That is because, at the end of the 25 years, the amount to be repaid equals $1,000.

Corporate bonds, like in our example, usually have a face value of $1,000. If such a bond is sold for $1,000, it is known as a par value bond. However, other bonds, like government bonds, typically have large par values.

3. Coupons and the coupon rate:

In finance, coupons are the annual or semiannual interest payments made to the lender. In the previous example, $110 paid to you every year is the coupon payment that the bond provides you with. Bonds that have equal periodic coupon payments are known as level coupon bonds.

Bonds that offer no coupon are known as zero-coupon bonds. The most prominent zero-coupon bonds are US savings bonds and US treasury bills. Bonds are sometimes called bills when the maturity of those bonds is less than one year.

The coupon rate is the size of coupons received annually divided by the face value of the bond. In the example, the annual coupon received is equal to $110. Therefore, the coupon rate equals $110 / $1,000 = 11% = 0.11.

4. Yield to maturity

The yield to maturity is crucial in calculating a bond’s price or present value. Yield to maturity is the interest rate that other bonds with similar natures and identical structures earn

In our example, the YTM was mentioned to be 11%. In this case, the yield to maturity is equal to the coupon rate, but this is not always the case. YTM will only be similar to the coupon rate if the bond is sold at par value. YTM will be greater than the coupon rate if it is a discount bond.

Types Of Returns under Bonds

Now that we know why discount bonds exist, let us see how an investor gains a return on the investment of such bonds. Discount bonds typically have two types of recovery:

1. Interest payments (coupons)

The periodic coupon payments are one source of return for such bonds. Coupon payments can be made annually, semiannually, quarterly, and monthly. This type of return is called current yield, and it is always less than the yield to maturity in such bonds.

Calculating the current yield is simple. It is equal to the annual coupon, the payment that the bond earns divided by the face value of the bond. It is important to remember not to divide the annual coupon by its current price but only by its face value.

2. Appreciation of the bond

Since the bond is purchased for less than its face value, the asset will appreciate until its maturity. This is the second source of return for an investor investing in a discount bond.

This type of return is called capital gains yield. As its name states, it measures the percentage increase in the value of an asset over time. It is calculated by dividing the increase in the price of the bond by the initial cost of the bond at which it was purchased.

Calculating the price of a discount bond

The current price (or current value) of a bond depends on several factors:

- Its face value

- The yield to maturity

- The coupon

- Time to maturity

Finding the price of a bond is a straightforward exercise of discounting. To calculate the current value of a bond, we need to find the present value of both its face value and the stream of coupon payments. Finally, we must add both current values to find the bond's price.

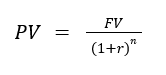

To find the present value of the $1,000 face value, we use the formula of the current value of a lump sum. This formula requires us to know the time to maturity, the face value, and the yield to maturity, which will be used as a discount rate. The formula is:

- FV is the future value, and in other words, the face value of the bond

- n is the number of periods until the bond matures

- r is the yield to maturity of the bond

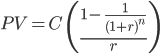

To find the present value of the coupon payments, we have to use the formula of the current value of an annuity. An annuity is characterized by periodic payments of equal sizes between two points in time. Coupon payments are an annuity. The formula is:

- C represents the periodic coupon payments

- n is the number of periods until the bond matures

- r is the yield to maturity of the bond

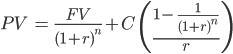

Therefore, the current price of the bond is simply the addition of the two previous formulas:

Let us take an example. Suppose corporate bonds are being issued with 15 years to maturity with a face value of $1,000. The market interest rate for similar bonds is equal to 10%. The coupon rate for these bonds is 8%, paid semiannually.

We have all the information required to find the price of the bond. As mentioned, the steps to calculate this value are as follows:

- Find the present value of the face value (lump sum)

- Find the present value of the coupon payments (annuity)

- Add the two current values to find the bond price.

Note:

Since coupons are being paid semiannually, the YTM must be divided by two and the number of years multiplied by two to denominate them in “half-years.”

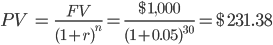

The present value of the $1,000 face value is:

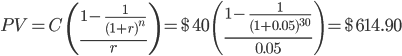

Now we have to calculate the present value of the coupon payments. The coupon rate is 8%. Therefore, annual coupon payments are $80. Since coupons are paid semiannually, then semiannual coupons are $40. The present value of the coupon payments is:

Therefore, the bond has a current price of $231.38 + $614.90 = $846.28. Therefore, this bond is a discount with a discount of approximately $154. This is coherent with the fact that the coupon rate is less than the YTM, which means the price of the bond must be less than its face value.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?