Greater Fool Theory

This theory suggests that investors can sometimes profit off purchasing an expensive asset by selling it at a higher price to a greater fool.

What Is the Greater Fool Theory?

The Greater Fool Theory suggests that investors can sometimes profit off purchasing an expensive asset by selling it at a higher price to a greater fool. After all, value is in the eye of the beholder.

Generally speaking, this theory aims to justify the actions of individuals who purchase excessively overpriced securities. As a result, this theory often leads to asset bubbles where the deposit price has diverged significantly from its intrinsic value.

There have been many cases where the greater fool theory has been prevalent, from the tulip mania to the modern-day NFT craze. Yet, no matter how irrational this theory might be, some explanations exist for these puzzling phenomena.

In neoclassical finance, investors are often assumed to be perfectly rational and armed with the necessary knowledge while accessing freely available information.

However, the truth is that financial markets are so easily accessible that many market participants do not possess the same level of understanding as your average CFA charter holder.

Instead, some investors are subjected to behavioral biases. They develop heuristics when analyzing stocks and can get emotionally attached or biased towards certain assets. Concepts such as conservatism or anchoring are highly noticeable in many retail investors.

One of the main reasons behind the greater fool theory is the fear of missing out. So when other investors saw Jared make $84,000 in a single NFT sale, they didn’t want to miss out on that opportunity as well - they thought that if they did the same thing, they’d profit too.

However, these investors sometimes forget that markets can be fickle and sentiment-driven. The market may have viewed NFTs as a valuable investment, but will that valuation last forever if it doesn’t have intrinsic value?

If the music stops before Jared can sell his NFTs, then he risks losing a significant amount of money if the value of the NFT tanks. After all, value is in the eye of the beholder.

Understanding Greater Fool Theory

Imagine this: you’ve been a hard worker your whole life: straight A’s in school, 1550 SATs. Not only were you the president of the finance society in your high school, but you were also an active volunteer for a charity you don’t care about (you just needed to seem like you did).

You managed to get into Stanford, but you know that the hustle doesn’t stop there. So you start applying for spring internships and cold emailing bankers who are alumni of Stanford. After all, the standard route is spring internship to summer internship to full-time employment.

Your peers have started rushing Kappa Alpha, but the only Alpha you know is the percentage of returns that your investment portfolio has outperformed the S&P 500.

As a result, you’ve decided that a position in your student-run investment fund is more critical than fraternities.

Fast forward to the future, and you’ve finally made it: you’re a full-time analyst in JP Morgan’s sales & trading division. But, despite being an analyst, you consider yourself to be quite an expert in capital markets. After all, you helped your student-run investment fund return 69% annually.

During the Christmas break, you meet your extended family. Ironically, your non-target sub-2.5 GPA cousin Jared tells you that he’s been investing as well. You ask him about his investment strategy and his portfolio’s Sharpe ratio - he tells you he doesn’t bother about that stuff.

Instead, he tells you that he made over 420% returns just six months after investing in a rock NFT. He bought the rock image for $20,000 and sold it for $104,000. He now thinks he’s better than you and says he’d be happy to give you some investment advice. Ironic.

He tells you that he’s reinvested all his capital into some other NFTs. While his abnormal returns upset you, you think he is a fool lying in wait for a more fabulous sport to buy his NFTs. One day he will be left holding the bag as the greater fool if he keeps this up.

Greater fool theory and intrinsic value

Although this article uses NFTs as an example of the greater fool theory, it is difficult to say whether NFTs are currently overpriced. Many people are divided regarding the NFT space (or even crypto).

The simplest explanation regarding NFTs is that they are essentially digital art. Although these JPEGs can be widely distributed and shared among anyone online, NFTs utilize blockchain technology to ensure that the ownership of that image very clearly belongs to a singular individual.

NFTs rely on one of the five characteristics that money has: scarcity. Similar to the Mona Lisa, diamonds, or even baseball cards, there are only so many Bored Ape NFTs worldwide.

Yes, there could be screenshots of those same NFTs, but there are also replica Mona Lisas, fake diamonds, and baseball cards that cost only a fraction of the real thing. Therefore, thanks to blockchain technology, Jared will always know that he owns the actual rock JPEG.

Even though NFTs are scarce, does that justify a price tag of millions of dollars? There was one JPEG that even sold for $91.8 million. So there could still be a bubble, an outcome of the greater fool theory.

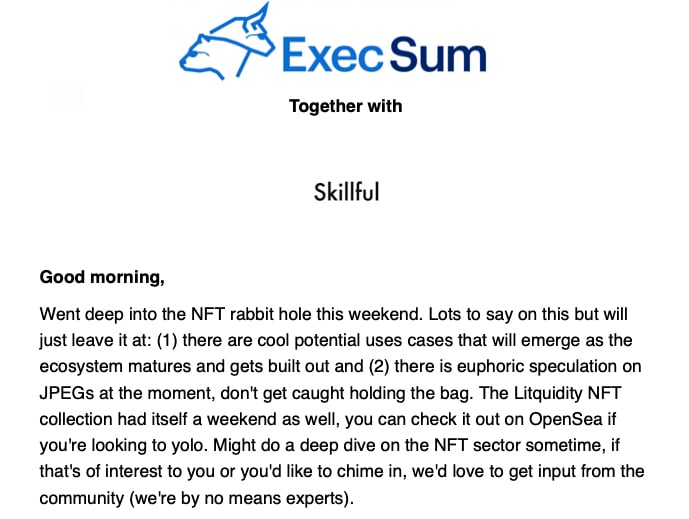

Below you will be able to see the opinion of a popular Instagram page (Liquidity), which now does venture capital investing. They were initially against the concept of NFTs but changed their mind later. These images were taken from their newsletter - Exec Sum.

12th August 2021

30th August 2021

It seems that even Liquidity (whose founder is an ex-investment banker and private equity investor who graduated from an ivy league) joined the hype. However, their stance is seemingly clear: do NOT get caught holding the bag.

An object’s value might not necessarily be considered as a result of the labor and cost of material that went into its production. Instead, it could be viewed as a result of how badly other individuals want it.

The truth is that many companies have included NFTs as a part of their operations. For example, Visa spent over $150,000 purchasing a “CryptoPunk” NFT, and many multinational corporations (Gucci, Coca-Cola, etc.) have even minted their NFT collection.

Therefore, perhaps there is no bubble in the NFT space, and that rock JPEG is seriously worth that $84,000 price tag. Only time will tell. If you want to learn more about NFTs, here is a video of Ben Shapiro discussing this specific topic:

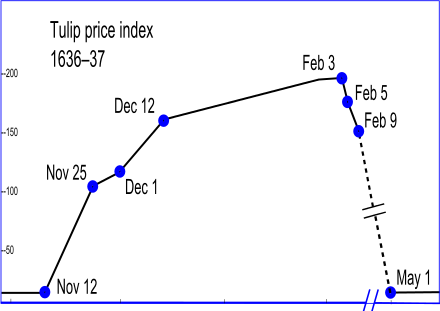

Tulip mania

This case study is 100% real and happened sometime in the 17th century. It happened in Holland and was believed to be one of the earliest recorded market crashes. The price of tulips during the bubble went as high as 20 times its regular price.

During the 1630s, Holland was a famous international port due to its spice trade. At that time, wealthy individuals also had a particular affinity for tulips as they looked pretty. Because of this, tulips became very popular (and expensive).

The tulip flower was expensive because it took a significantly long time (over seven years) before the tulip seed even formed a bulb. Furthermore, the tulip plant didn’t originate from the Netherlands; it came from Central Asia.

The strange part was that most merchants trading tulips didn’t even see the flower

blossom. Instead, they were buying and selling its bulbs, with each merchant hoping to sell the bulb at a higher price than what they got it for (sounds familiar).

This was because tulip bulbs were sturdier than the blossomed flower. Therefore, bulbs could be more easily traded without damaging the commodity than the flower itself. Unfortunately, at this time, many merchants were overvaluing these tulips and seriously overpaying for the plant.

At the height of the bubble, individuals even traded their houses for these tulips. Unfortunately, speculation and greater fools pushed prices past their intrinsic value (it’s just a flower).

One interesting aspect was that because of this, the Dutch people created a system that enabled merchants to purchase tulips at later dates with guaranteed prices, likely to be the world’s first recorded futures market.

However, what comes up must eventually go down. Soon enough, people realized that a simple flower was not worth the same value as a house. As a result, no one wanted to buy it anymore, future contracts were not honored, and the market finally crashed.

Although it is difficult to find accurate data, Earl Thompson estimates the price index of tulips to look something like this:

The music had finally stopped, and there were no greater fools in the market to sustain the sky-high valuations of the tulip plant. The bubble finally popped, and the individuals left with the bag were forced to sustain heavy losses.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?