Naked Put

A specific strategy used by investors who are bullish on the underlying security.

What is a Put Option?

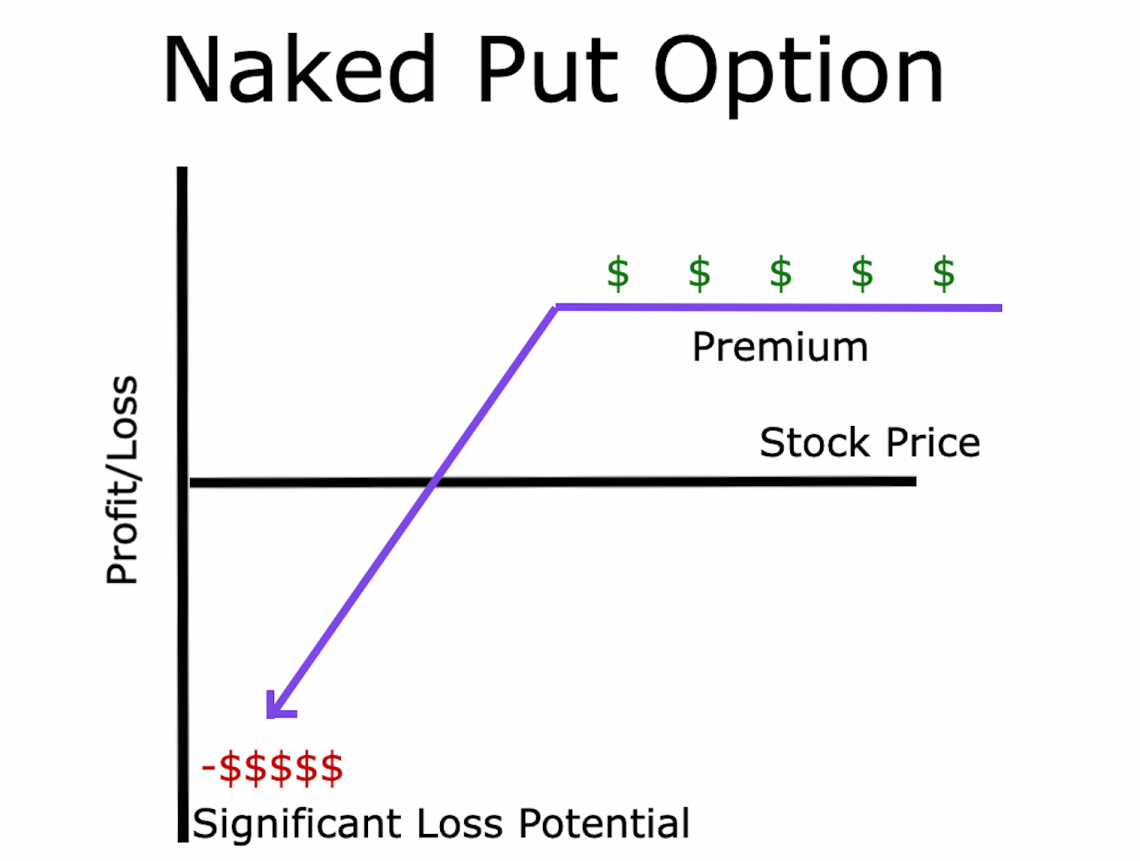

A naked put is a specific strategy used by investors who are bullish on the underlying security. This type of options trade involves selling an option contract of a security that the investor does not have the cash to secure.

In simple terms, an investor using this strategy is essentially betting that the price at expiration will be above the option's strike price (more on this later). Any price at expiration below the strike would mean fewer profits or even a loss on the trade.

Because this strategy is based on selling a contract, the primary goal is to collect the contract premium. Other comparable strategies, such as the cash-secured put, also aim to collect premiums but differ in terms of collateral used if the option were exercised.

With a cash-secured-put, cash is held in reserve to ensure it can fulfill buying obligations to the contract owner. A naked put also involves selling a put option, but the investor does not hold cash as collateral. For this reason, they are considered to be naked.

This is because the investor could be left with a devastating loss when the stock price drops sharply. They have no downside protection (in the form of cash) to ensure they can buy shares after the price shift.

In summary, these are the most important things to take note of when using the naked put strategy:

- The profit is capped at the premium earned immediately after selling the contract.

- The losses can be quite large (it is a risky strategy).

- The investor is betting on an upward price movement. They are bullish.

Put Option Basics

A put option is a type of financial instrument used to speculate on the price of a security. Like other option contracts, its value is determined by changes in the underlying security price.

A put option gives the right to sell 100 shares of the underlying security for a set price up until the expiration of the contract.

A litany of specificities determines how an option contract is priced and its value changes.

There are only a few must-know components for investors interested in options trading to understand how the contract works. These include:

- Strike Price

- Expiration Date

- Premium

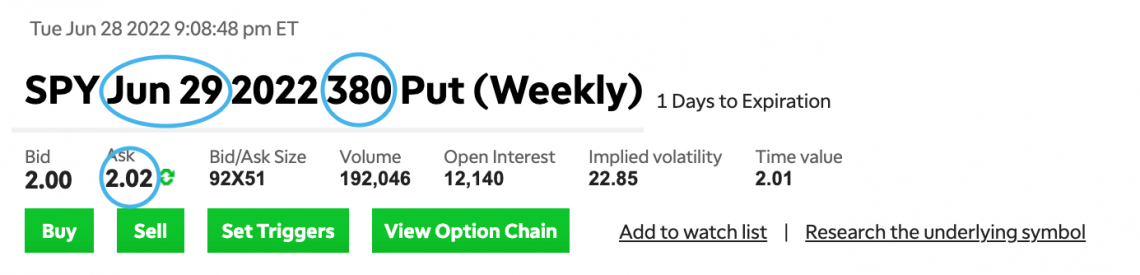

In the example of this SPY put option, the strike price is $380, the expiration date is June 29, 2022, and the premium for buyers is $2.02. The premium for buyers is also known as the ask.

The strike price is the price that determines the contract's money. In the case of a put option, a market price of the underlying below the strike price indicates the contract is in the money. A market price above the strike would mean it is out-of-the-money.

The expiration date is when the value of an option contract is finalized. It can no longer be exercised after that date. Contracts are typically only exercised when in the money, as there is no benefit to exercising an out-of-the-money contract. One will lose money exercising an out-of-the-money contract.

It is also worth noting that specific options can be exercised before expiration, which is unusual. Investors typically close their positions by selling their options contracts to another investor. In the case of a short position, investors close by purchasing back the sold contract.

The premium is the price of purchasing the option. It is expressed as a price per share. For the example SPY option above, the premium is $2.02. This $2.02 premium translates to a purchase cost of $202, $2.02 for each of the 100 shares in the contract.

Contract Price = Premium x 100 shares

A simple way of conceptualizing premium is by considering it the price an investor is willing to pay to have the leverage of 100 shares temporarily. Instead of needing capital to purchase 100 shares, an investor must pay the premium for the option.

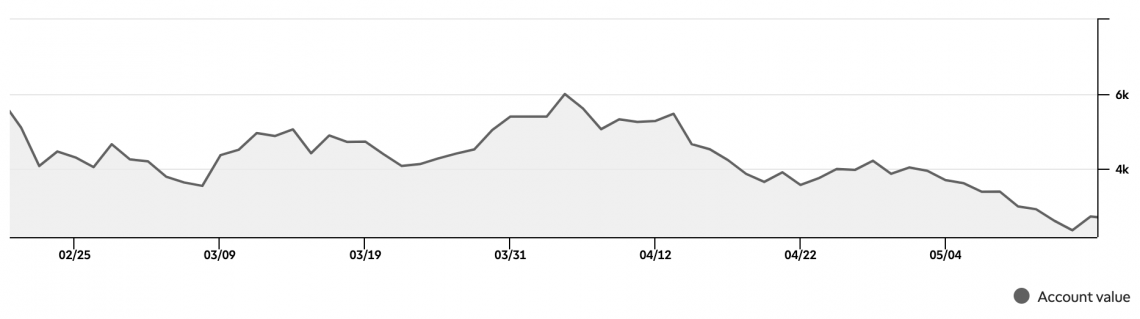

Because the contract represents 100 shares, its value can change rapidly, especially as the option nears expiration. As a whole, this can lead to portfolio volatility if the contract has a high portfolio weight. One may observe sharp changes in portfolio value from option contracts:

Buying A Put

As mentioned earlier, a put option gives the owner the right to sell 100 shares of a company at a certain price by a certain time. Someone buying a put option is both hoping for and expecting a price decrease.

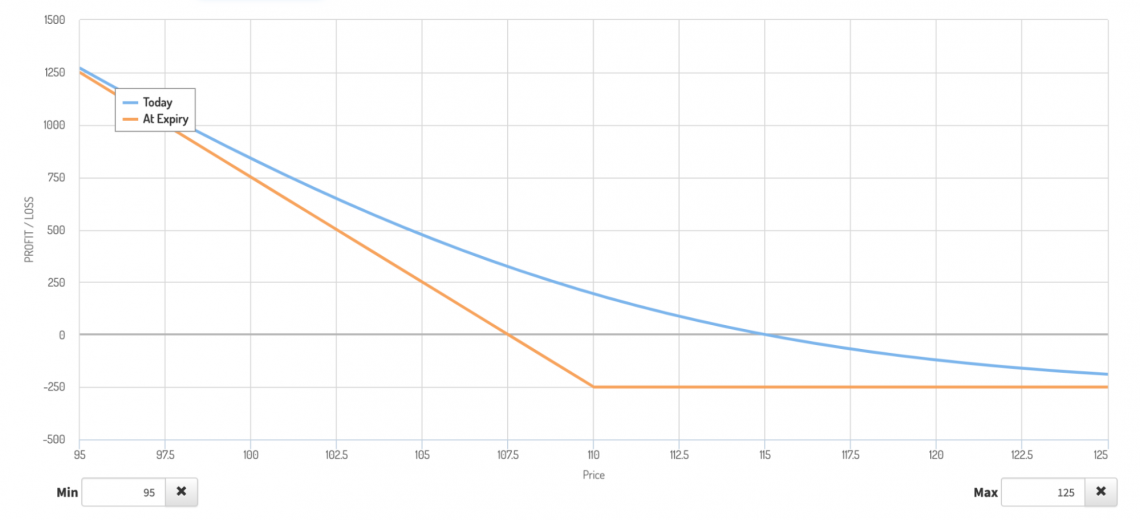

Let's look at an example of a put option on company XYZ that expires in 30 days. The current market share price of company XYZ is $115. The strike price is $110. The premium is $2.50.

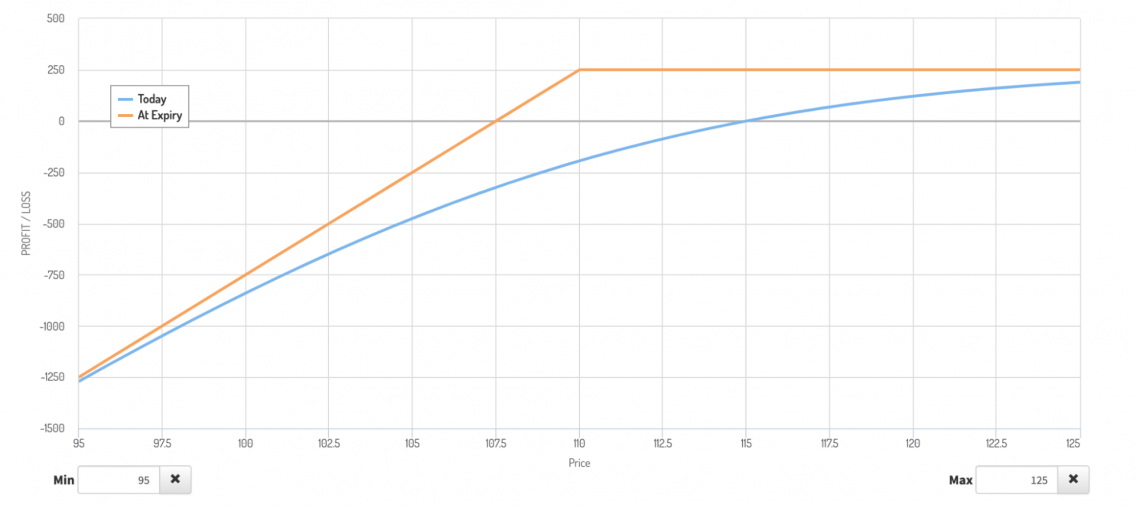

Looking at the profit and loss chart, we can see how the contract value changes depending on the market share price at expiration.

There is a difference between the value of the option contract today and at expiration, as the time until expiration gives the contract value. This time is valuable because the price can still move, affecting the contract's moneyness at expiration.

Let us say, at expiration, the price is unchanged and remains at $115. The contract is not exercised, as it allows us to sell at $110. This option is worthless to us since the price of $115 is above $110.

Because the option is worthless, the purchaser is left with a $250 loss from paying the premium to purchase the contract.

Let's say, at expiration, the price dropped to $109. It makes sense to exercise the option, as it allows the purchaser to sell 100 shares for $110. The investor purchases 100 shares at $109 and immediately sells them for $110 to the seller of the contract.

This $110 value from price differences is why the investor chooses to exercise the contract. However, the premium paid for the contract was $250. The investor still has a loss of $150 on the trade.

Let's say, at expiration, the price drops to $100. The contract is exercised. The shares purchased at $100 sell for $110. This earns the investor $1000. Subtracting the premium, the investor’s profit is $750.

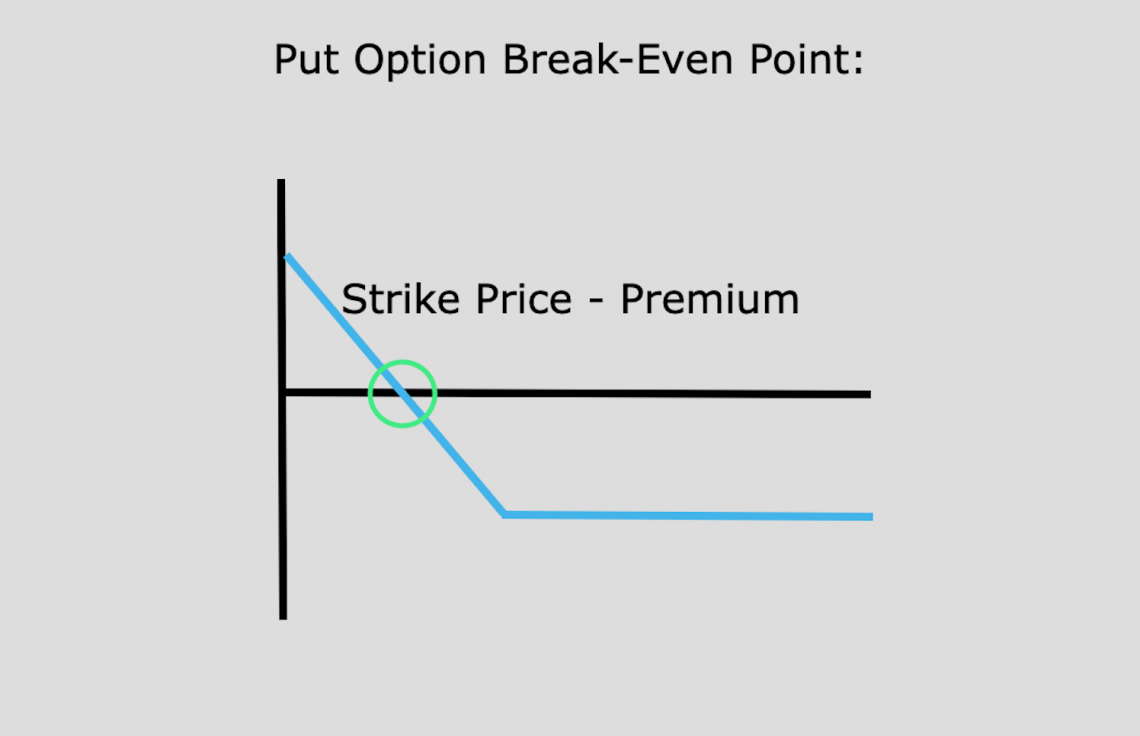

As we can see from these different scenarios, the buyer is only profitable if the price drops below the strike price. The premium initially paid in the contract is the amount the market share price must fall below the strike. In this example, the break-even security price is $107.50.

Buying a put has the potential for huge gains if the underlying price continues to decrease. The losses are always capped at the original price the investor paid to obtain the contract.

Selling A Put

Selling a put option is the opposite end of the same trade. The seller collects the premium for assuming the risk of fulfilling the contract. They are obligated to sell 100 shares of the underlying at the strike price if the option is exercised.

It follows that the seller does not expect the share price to reach the strike.

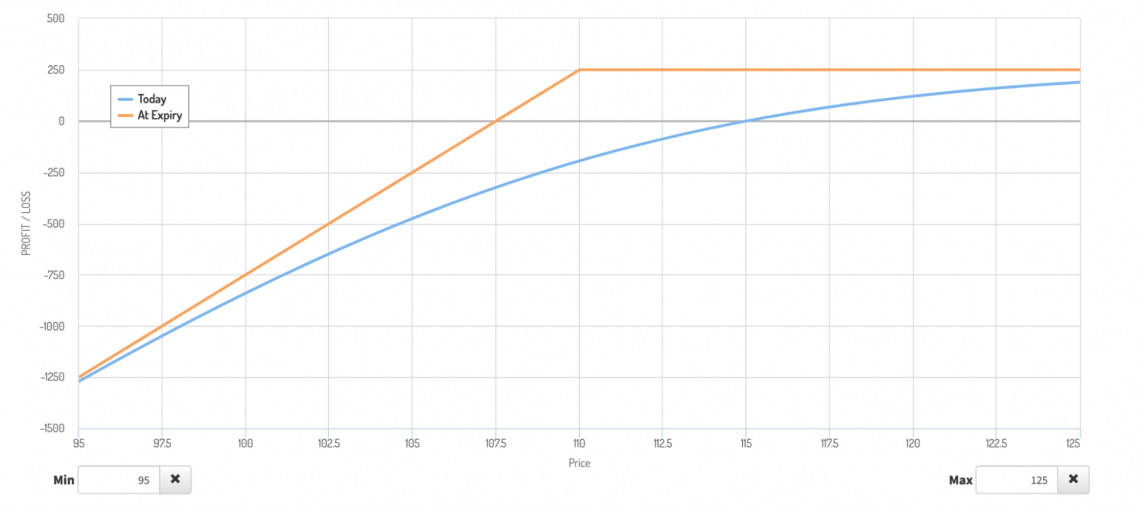

Using the same put option contract example, we can see that the profit and loss chart is simply reflected over the x-axis.

We can see from the graph that the seller's max profit is constant until the price reaches the strike. This max profit amount is the premium. Once the share price moves below the strike, the seller’s profit decreases and becomes a loss at the break-even point.

If the price moves significantly below the break-even point, the seller can be left with a large loss from having to purchase shares at the strike price, far above the market price.

Looking closer at the graph, we can see that the seller’s profit of $250 corresponds with every share price that the buyer has a $250 loss. Once the seller has a loss, the buyer begins to profit. The seller’s loss remains equal to the buyer’s profit.

Naked Put Strategy

As briefly stated, the strategy is for investors to expect the underlying security price to decrease. The primary difference between a naked put and other strategies that include selling a put option is the lack of collateral held by the seller.

Because the seller must fulfill the contract if exercised, the collateral for a right-to-sell (put) contract is the cash needed to cover the maximum loss. This would be the cash needed to purchase 100 shares at the strike price for an exercised put option.

Naked Vs. Cash-Secured Put

For an investor looking to collect the premium of selling a put option without liquidity risk, a strategy known as the cash-secured put could be used. To execute this strategy, the investor would sell one put option while setting aside cash to purchase 100 shares at the strike.

Cash Reserve = Strike Price x 100

Revisiting the same example as before, we can see that the profit and loss graph is identical between a cash-secured and naked put. So why is the risk any different?

If an investor used either strategy, the maximum profit would be $250, and the maximum loss would be $11,000. If an investor had $11,000 in cash set aside, the risk would be lower because there is no chance of liquidating other positions in their portfolio.

Assuming a share price drops to zero in the worst-case scenario, the seller of the option would be forced to buy shares at $110. If they had $11,000 on hand, they could purchase those shares and realize the loss.

If they did not have $11,000 on hand, they would be forced to close other positions to rebalance their portfolio with more cash. That cash would be immediately lost, as it would be used to purchase shares.

In cases where the portfolio balance was less than $11,000, the entire portfolio would be liquidated! As we can see, a naked put is much riskier than its covered alternative.

Naked Put Vs. Long Call

Another viable comparison to the naked put strategy is the long call. The purchase of a call option allows the buyer to buy shares at a specific price.

Like selling a put contract, purchasing a call is also a bullish strategy. The investor expects the share price will be above the strike price at expiration.

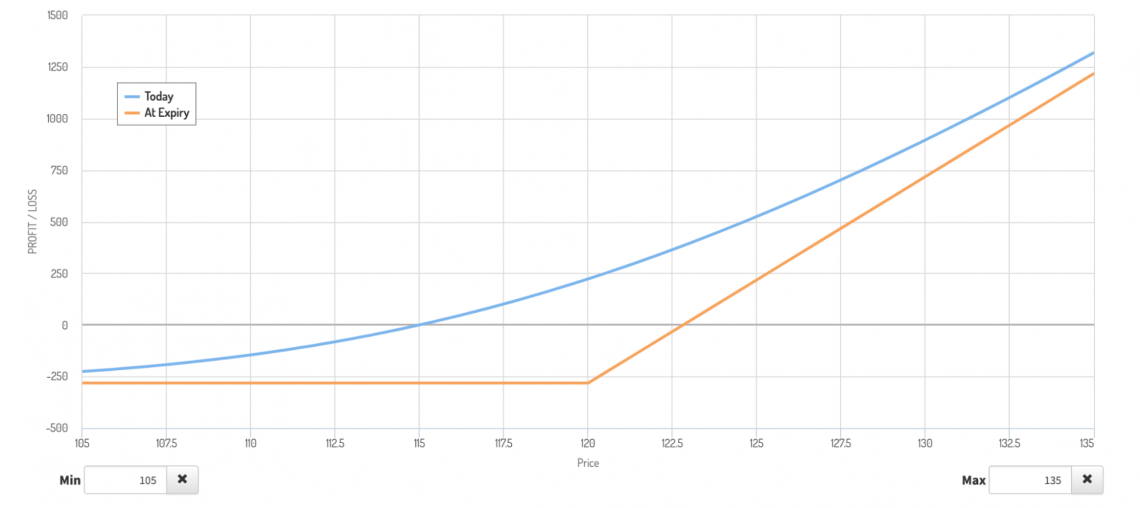

Revisiting company XYZ, an investor notices a call option expiring in 30 days at the $120 strike. The option premium is $2.81.

Looking at the long call profit and loss graph, it is clear that there is an opportunity for unlimited profit as long as the price of the underlying increases.

Like buying a put, purchasers of call options break even when the underlying share price moves beyond the strike price by the premium amount. In this case, that break-even point is $122.81.

Interestingly, for the purchase of this call option to have the same profit as selling the put, the same distance out of the money, the price would have to rise to $125.31. On the other hand, the sold put would simply have to remain above the strike.

Back to the Naked Put

Compared to the cash-secured put and long call strategies, the unique utility of a naked put is evident.

Unlike the less risky cash-secured put, selling a put without collateral allows investors to collect a premium without having to reserve cash to purchase 100 shares of the underlying stock at the strike if the option is exercised.

Seeing as it is unlikely for a given stock to tumble to zero, this cash that would be sitting idle can be used to chase more returns. This is attractive to investors, especially those with higher risk tolerance.

If an investor wishes to make a bullish bet without the opportunity cost associated with a cash-secured put, they may opt for a strategy such as the long call. This is because the long call only requires the investor to pay a premium rather than hold a large cash reserve.

However, as shown in the example, investors using a long call strategy need much more to happen to realize any profit. Investors who instead opt to use the naked put strategy can immediately collect premiums and enter a trade with a higher likelihood of profit.

Recall that the price simply must not drop too much for a seller of a put to stay profitable, whereas a long call demands a price increase to break even.

While the naked put has its advantages, investors must also be wary. The difference in profitability around the strike price can be reconciled by the potential for massive gains when buying a call option and the potential for huge losses in the case of selling a naked put.

For this reason, a naked put is much riskier for an investor than buying a call if the investor is bullish on the underlying. Ultimately, investment strategy choices come down to personal preferences over how much overall portfolio risk the investor is willing to take on.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?