Cross Elasticity Demand (XED)

An economic term that quantifies how responsive the quantity demanded of one commodity is when the price of another good varies, ceteris paribus.

What Is Cross Elasticity of Demand?

The cross elasticity of demand (Xed) is an economic term that quantifies how responsive the quantity demanded of one commodity is when the price of another good varies, ceteris paribus.

It deals with how sensitive demand for a product responds to shifts in the price of another good.

In practice, the prices of other "related" commodities impact the quantity wanted of good in addition to its price (price elasticity of demand). For instance, an increase in the price of Coca-Cola affects the demand for Pepsi.

Various products commonly relate to one another on the market. This may imply that a product's price alteration may impact the demand for the product, either favorably or unfavorably.

An increase in the price of a substitute good increases the demand for the given product and vice versa.

Similarly, an increase in the price of a complementary good decreases the demand for the given product and vice versa.

This measurement often referred to as cross-price elasticity of demand, is obtained by dividing the percentage change in the quantity demanded of one good by the percentage change in the price of the related good.

Businesses and organizations calculate this ratio using the cross-price elasticity formula to grasp better the market they serve.

The nature of the commodities in relation to their uses is the primary determinant of Xed. It is high when the two commodities satisfy the same need equally well. There are three product relationships to look at when describing cross-price elasticity.

XED And Its Relationship with Different Types Of Goods

We will examine some of the different goods types and their relationship with Cross Elasticity Demand.

First, some products are closely linked to one another and are occasionally referred to as substitutes. These goods compete in the market for the same consumers.

- The XED for substitute goods is always positive since the demand for the good increases as the price of the substitute increases.

- A price increase in a substitute product will result in increased demand or positive cross-price elasticity.

Second, some products are used in combination with one another. As a result, the consumption of related products is directly impacted by the demand for one product. These goods are referred to as complementary goods.

- XED for complementary goods is negative because as the price of the commodity under observation increases, the consumption/ demand of the item closely related to it drops, given that the cost of the good has fallen.

- A price increase in a product that is a complementary product will result in decreased demand or negative cross-price elasticity.

Products in the last category are completely unrelated to one another. Therefore, the consumption of these goods is unaffected by one another.

- XED for these goods is zero because the price changes of one good will cause no changes in the amount of consumption of the good taken into consideration.

- Such products are said to have zero cross-price elasticity.

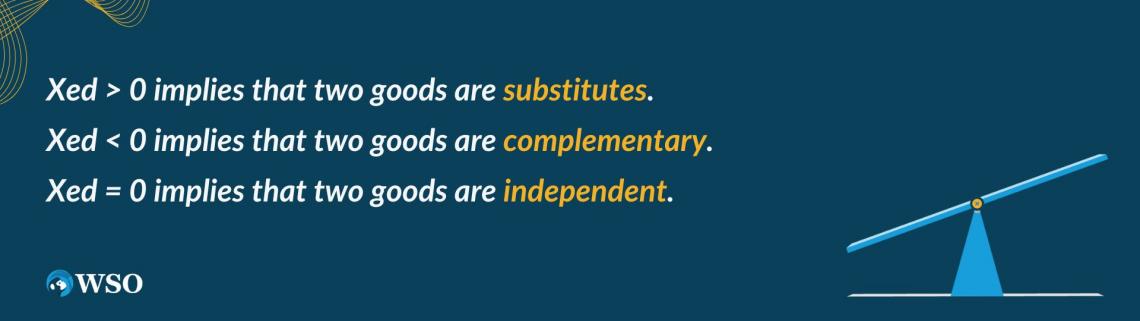

So, in summary:

- Positive Xed for substitute goods,

- Negative Xed for complementary goods,

- Zero Xed for unrelated goods.

Reflections of Authors on Elasticity Of Demand

Alfred Marshall's "price elasticity of demand" theory foresaw how prices and quantities would fluctuate in relation to one another.

According to him, “the elasticity (or responsiveness) of demand in a market is great or small according to the amount demanded increases much or little for a given fall in price and diminishes much or little for a given rise in price.”

Professor Stocking first considered that the movement of two prices in the same direction explicitly demonstrates a high cross-price elasticity in the Cellophane instance because he believed that a change in the price of one product would drive a price change of its rivals in the same direction.

However, from 1924 to 1940, du Pont cellophane prices fluctuated independently of its alleged rivals (waxed paper, vegetable parchment, etc.); these independent price changes indicate non-competitive pricing between cellophane and its competing goods.

Therefore, Professor Stocking's concentration on the same movement of prices was too rigid, as the cost of cellophane fluctuated as a result of three factors:

- A shift in demand brought on by the pricing of competing goods

- The cellophane's production function

- The slope and position of the cost curves for competing goods.

In other words, since price change results from cost and demand considerations, the competitive connection (cross-price elasticity) between two items cannot be merely determined by the price change.

Note

The cross-elasticity of demand should be either positive or negative to show whether there is a complementary or substitutive relationship between two items, as opposed to a high positive or low positive elasticity determined by monitoring respective price changes.

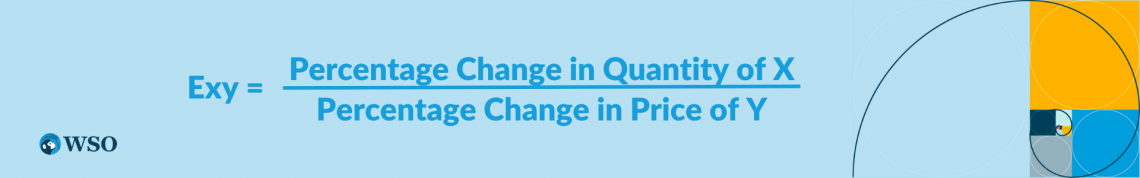

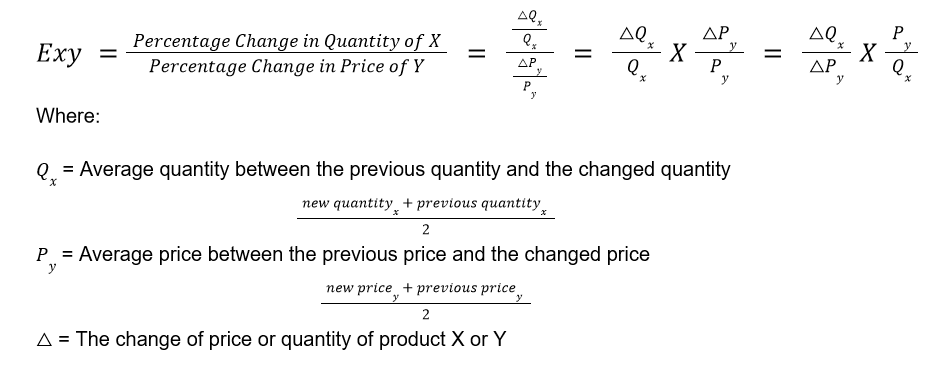

Cross Elasticity of Demand Formula

If the formula of XED is put into simple words, it's the ratio of the percentage change in the quantity of product x and the percentage change in the price of product y.

Here is the formula for XED:

Contrary to income elasticity, the Qx and Py in cross-price elasticity are determined by averaging the changes in either the price or quantity demanded.

Xed > 0 implies that two goods are substitutes. When the price of A rises, shoppers buy more of B.

As an illustration, butter's Xed concerning margarine is 0.81; a 1% rise in the price of margarine will increase by 0.81% in demand for butter.

Xed < 0 suggests that the two items are complementary. When the price of A rises, consumers buy less of B.

As an illustration, the demand for entertainment is cross-elastic concerning food at 0.72, meaning that a 1% increase in food prices will result in a 0.72 percent fall in demand.

Xed = 0 means that two goods are independent (a change in the price of item A has no bearing on a change in the demand for good B) and that price adjustments for product A have no impact on the need for product B. For instance, food and clothes.

Two items are more substitutable and thus more competitive when the positive cross elasticity of demand is high.

Similarly, the more complementary the two commodities are, the lower the negative cross-elasticity of demand. In general, monopolies typically have a low-positive cross-elasticity of demand.

For example, if the price of coffee rises from $100 per kg to $125 per kg, and consequently, the demand for tea increases from 10 kg to 15 kg, the Xed between tea and coffee will be -

Exy = ΔQx/ ΔPy * Py/ Qx

=5/ 25 * 100/ 10 = 2

So, if there is a 1% rise in coffee's price, the tea demand will increase by 2%.

Types of Cross-Price Elasticity

Depending on whether the cross elasticity of a product is positive, negative, or zero, there are three different types of cross-price elasticity.

1. Substitute Goods

Since demand for one commodity rises as the price of its substitute rises, the cross elasticity of demand for substitute goods is always positive.

Example 1: A and B, two rival airlines, are the ideal substitute product for illustration. Customers will probably notice the difference if Airline A decides to raise the round-trip ticket price of their flights even just a little bit.

Because Airline B is less expensive, more customers will choose it.

This mainly happens because consumers always seek to maximize utility. Therefore, the fewer people spend on something, the more satisfied they are.

Example 2:If consumers switch to a less expensive yet equally acceptable substitute, the quantity demanded tea (a substitute beverage) increases if coffee prices rise.

The cross elasticity of the demand formula reflects this, with positive increases in both the numerator (% change in the demand for tea) and denominator (the price of a coffee).

Note

For perfect substitutes, the Xed between them is plus infinity.

Example 3: Soap is an example of a substitute good; when the price of one brand of soap rises, so makes the demand for its rival's brand.

The cross elasticity of substitute demand is also known as positive cross-price elasticity.

Products that are substitutes fall into two categories: close and weak.

A) Close or Strong Substitutes

When a small price increase results in a significant rise in demand for the substitute good, this is known as a close substitute.

Strong substitutes for a given good have a higher cross-elasticity of demand.

Consider different tea brands; a price increase in one company's green tea has a more significant effect on the demand for green tea for a different company.

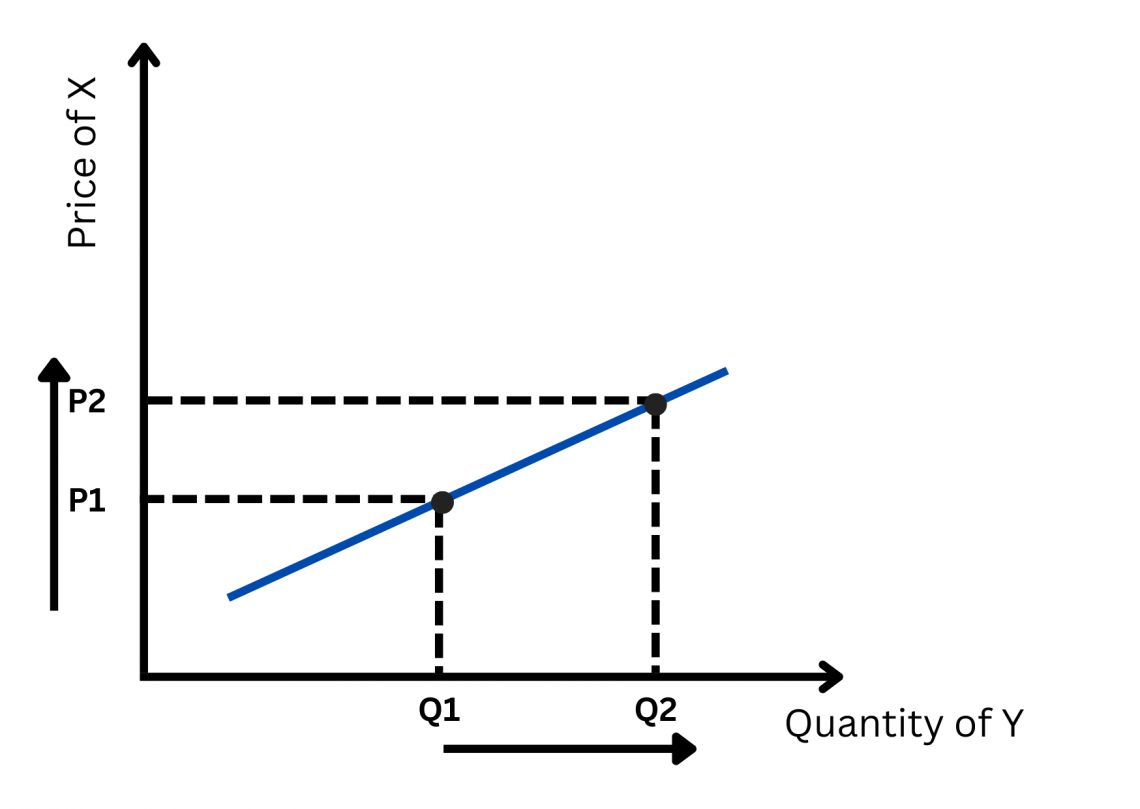

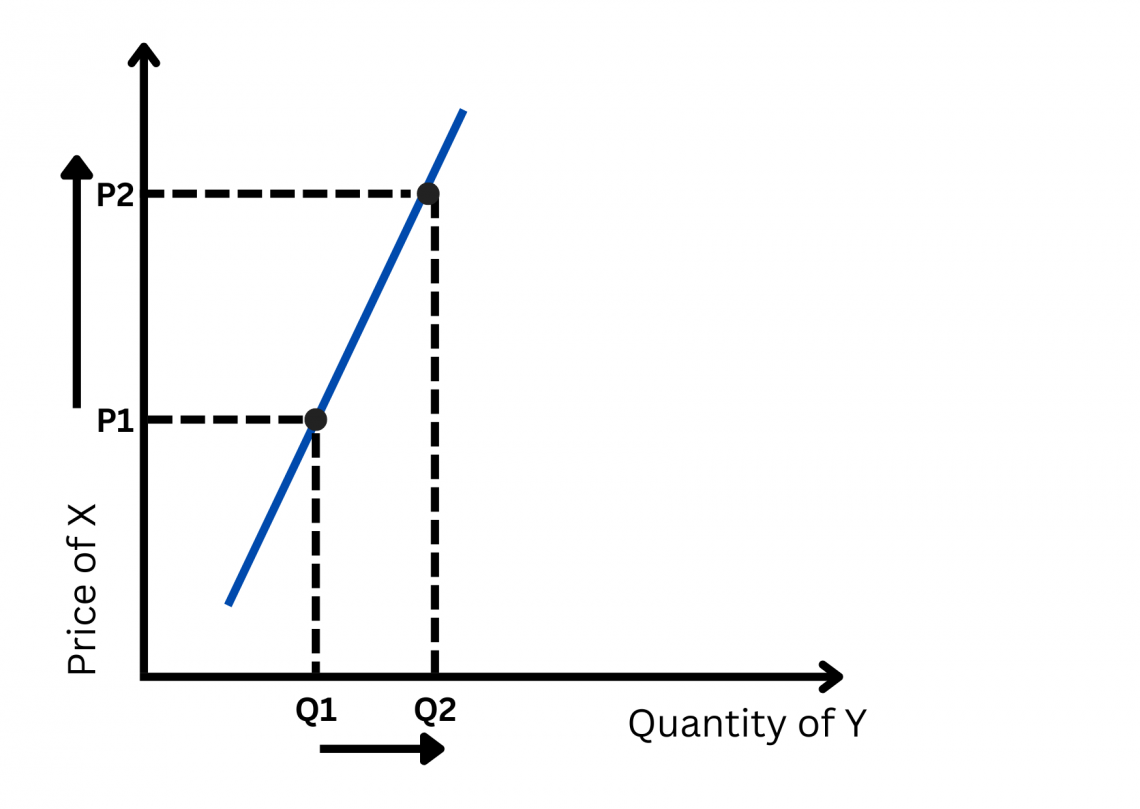

In this graph, the price of good X increases from P1 to P2, which results in a corresponding increase in the quantity of Y, a substitute good, from Q1 to Q2.

It is clear from the graph that the proportionate increase in price is less than the increase in quantity which makes the two goods close substitutes.

B) Weak Substitutes

For a weak substitute, a significant price rise for product X will only have a marginally positive impact on demand for product Y.

This is because the demand elasticity for the two products is positive but low. This frequently applies to alternatives for other products, such as tea and coffee.

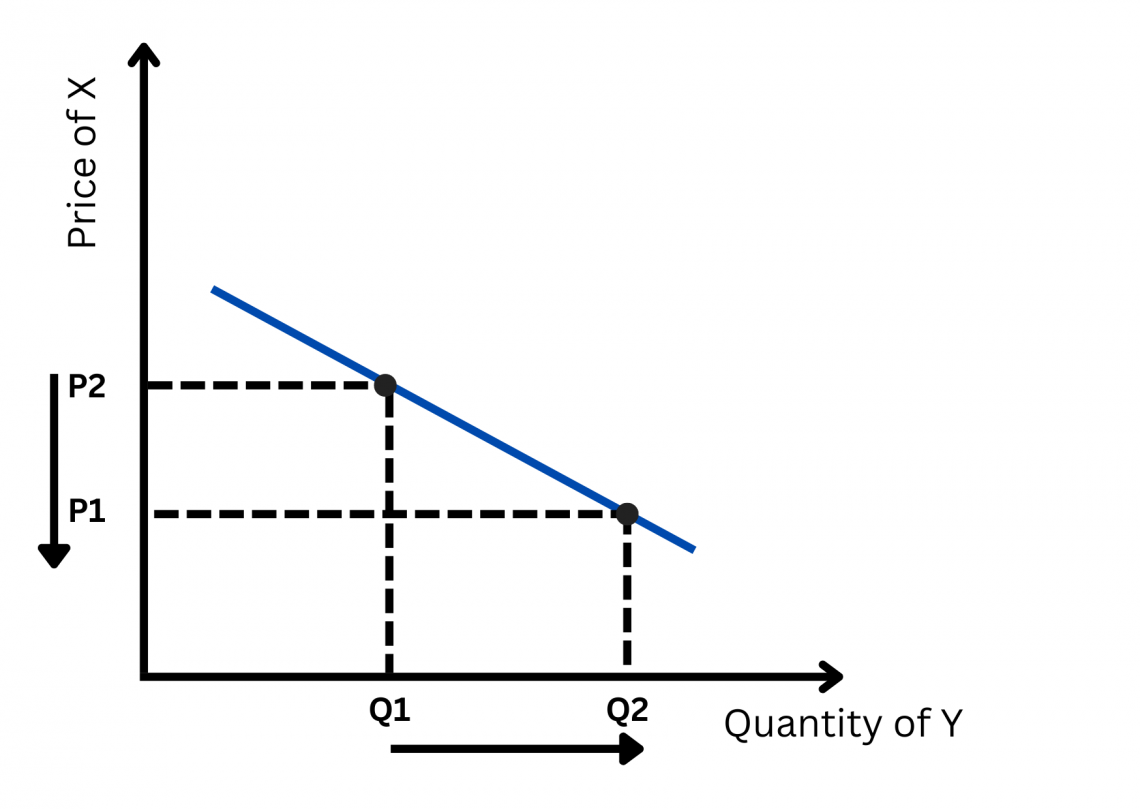

In this graph, the price of good X increases from P1 to P2, which results in a corresponding increase in the quantity of Y, a substitute good, from Q1 to Q2.

It is clear from the graph that the proportionate increase in price is more than the increase in quantity which makes the two goods weak substitutes.

2. Unrelated Goods

Items that have a coefficient of 0 are unrelated and independent from one another.

Products that are unrelated to one another have no impact on one another. This indicates that the cross-effect elasticity is zero, and a vertical line would be used to depict the graph.

The two products cannot be compared because they are unrelated.

Example

We can contrast two unrelated items, milk and laptops. There would be no difference in the number of laptops sold even if milk's price rose by 30%.

Similarly, if sugar prices rise by 15%, then it will not affect the price of petrol. The prices of such goods have a spurious correlation.

3. Complementary Goods

Demand for complementary goods has a negative cross-elasticity. Because there is less demand for the primary product when the price for the primary good rises, the demand for an item closely related to it and required for its consumption falls.

Example

If the price of tennis rackets rises, fewer people will need to buy tennis balls since fewer people will play tennis.

The denominator (the price of a tennis racket) is positive, while the numerator (the number of tennis balls demanded) is negative in the formula. Negative cross elasticity is the outcome. Customers will be forced to buy less due to the increasing joint cost.

In extreme cases, when the two goods are perfect complements, the Xed between them is minus infinity.

An eBook reader is an example of a complementary product. The purchase of eBooks and audiobooks will rise if eBook readers become more affordable to more people, who will then use them more frequently.

Complementary goods might either be strong or weak complements.

A. Close or Strong Complements

When a product has a strong complement, even a small price cut significantly increases demand for the complementary product.

Two products that are frequently utilized together are considered strong complementary goods. iPhones and iPhone cases, for instance. The number of iPhone cases sold will decrease as buyers purchase fewer iPhones.

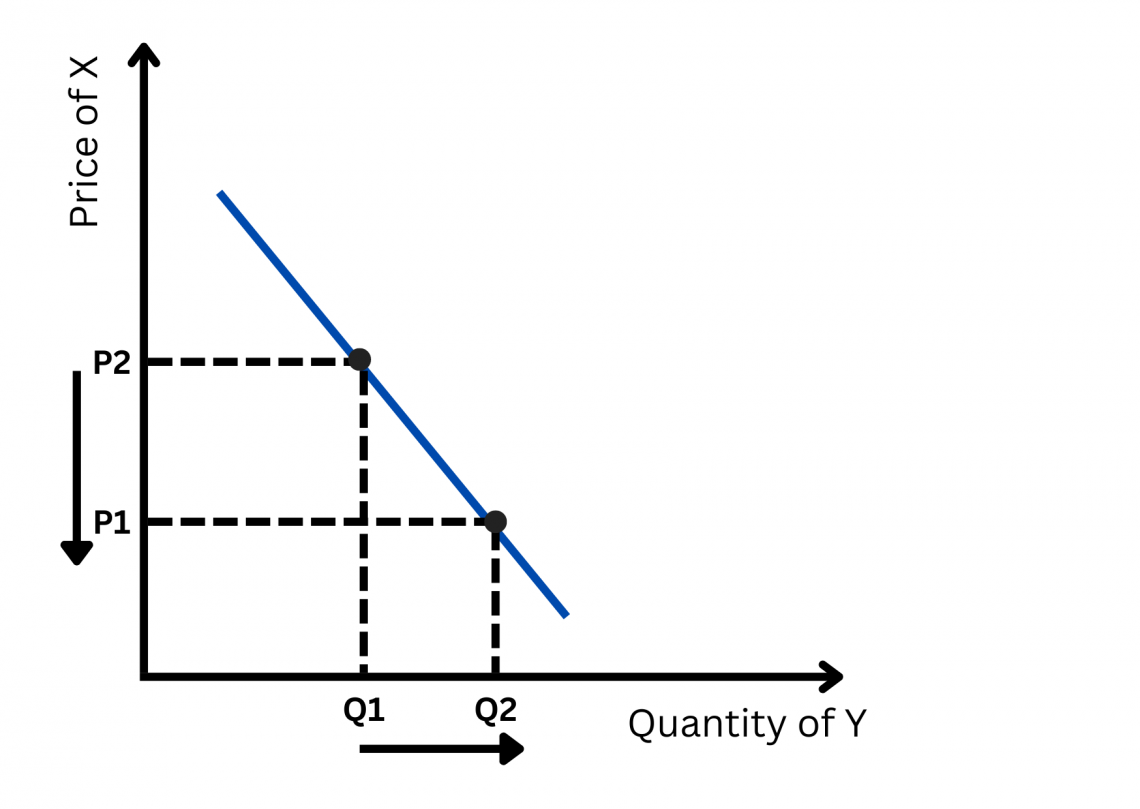

In this graph, the price of good X decreases from P2 to P1, increasing the quantity of Y, a complementary good, from Q1 to Q2.

It is clear from the graph that the proportionate decrease in price is less than the increase in quantity which makes the two goods close or strong complements.

B. Weak Complements

A significant price cut for weak complementary products results in a small rise in demand for complementary goods.

Therefore, weak complementary products are two goods utilized together but not frequently.

Pancakes and maple syrup, for instance. The association isn't as strong because different sauces and toppings are used in their place.

In this graph, the price of good X decreases from P2 to P1, increasing the quantity of Y, a complementary good, from Q1 to Q2.

It is clear from the graph that the proportionate decrease in price is more than the increase in quantity which makes the two goods weak complements.

Application and Implication of Cross Elasticity of Demand

There are various instances where the knowledge of cross elasticity of demand is required.

The governments make price-based policies after analyzing all the factors, one of which is Xed. Business firms also do market scanning to understand their position and the effect of other goods on their products; knowledge of cross elasticity of demand is essential.

Some of them are discussed below:

1. Contribution to Policy Improvement

To decrease alcohol use and mitigate the associated damages among their population, the governments of the UK and Scotland sought to utilize price-based policy interventions, such as establishing minimum unit pricing and raising taxes.

As it estimates the percentage change in demand for one type of alcohol owing to a 1% rise in the price of another type of beverage, the estimation of cross-price elasticities of alcohol in relation to other related beverages aids in setting price-based policy interventions.

2. Contribution to the Sustainable Supply Chain and Firm Reactions

The knowledge of cross-elasticity is important for business firms operating in markets with different brands competing with each other.

Businesses aware of the effects of high-positive cross elasticity of demand can lower operating risk by avoiding overstock and ensuring a sustainable supply chain.

They can use this information to determine how changing the price of one brand affects the other brands offered by competitors.

If two competing products, "A" and "B," have a Xed of 3, the manufacturer of product "A" can anticipate a 15% increase in demand for its product with every 5% increase in the price of product "B."

To prevent possible loss from "rivals'" strategies, cross elasticities are crucial when making decisions about price, output, and product in oligopoly and monopolistic competition.

Additionally, businesses can demonstrate that there are close alternatives and that customers have a good selection by demonstrating the high cross elasticities between their product and those similar to it. This will shield it from antitrust laws.

Product B's sales likely influence product A's sales if the coefficient of negative cross-price elasticity is high. There must be a decrease in the profit of A if the demand of A considerably depends on the demand of B.

The Xed, in this situation, warns businesses to carefully choose products with high dependence on complements.

When two items, A and B, are complementary, the demand for A declines when the price of B rises because A is utilized in conjunction with B.

The demand curve for product A shifts to the right in response to a decrease in the price of product B, suggesting an increase in the demand for A.

This results in a negative value for the XED. If A and B are substitute goods, a rise in the price of B will spur demand for A because consumers will be more likely to choose A over B, like McDonald's and Domino's.

Cross Elasticity of Demand FAQs

Cross elasticity of demand states the relative changes in demand for one good due to changes in the prices of its complements and substitutes.

A positive XED indicates that as the price of good “A” increases, there is a subsequent increase in the demand for good “B,” revealing that the two goods are substitutes. For instance, if Lipton's price goes up, the demand for Twinings increases.

A negative XED indicates that as the price of good “A” increases, there is a subsequent decrease in the demand for good “B,” revealing that the two goods are complements of each other, i.e., they are consumed together.

For instance, if car prices increase, then the petrol demand decreases.

The degree to which the elasticity of demand explains changes in the factors affecting demand impacts the quantity demanded.

The ratio of change in quantity demanded due to changes in the demand-affecting invariants is known as the elasticity of demand. The cross elasticity of demand measures how sensitive demand for one good is to changes in the price of a substitute or complementary good.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?