Negative Externalities

An indirect cost that a third party suffers when goods and/or services are consumed or produced

What are Negative Externalities?

Negative externality is a microeconomic concept. It is an indirect cost that a third party suffers when goods and/or services are consumed or produced.

Negative externalities commonly affect public resources, such as environmental pollution, where it is difficult to hold parties accountable. Moreover, since these are difficult to track, producers and consumers can create them without fear of being responsible.

This type of market failure contradicts the welfare theorem's assumptions, which say there should be no externalities under a free-market model.

A market failure occurs when the outcome of an economic transaction is not completely efficient, meaning that neither the consumer nor the producer fully realizes all costs and benefits associated with the transaction.

People will frequently purchase goods with an environmental component to compensate for their inability to buy them directly.

Individuals could capture this lakeside cabin's environmental and economic advantages in a perfect market. Thus, the demand for cabins would reflect the actual value of the property and the environmental benefits it delivers, making the cabin market efficient.

However, this is not the case in an imperfect market, where negative externalities, information asymmetry, and barriers to entry and exit are often present. One core issue is that an imperfect market produces an outcome that does not optimize efficiency.

Negative externalities occur when the social costs of an economic transaction exceed the private costs, leading to inefficiencies in resource allocation. For example, putting a monetary value on fresh air or a good ambiance is impossible because environmental goods are typically exposed to externalities.

Key Takeaways

- Negative externalities are indirect costs imposed on third parties when goods or services are consumed or produced. They often result in market failures where neither the consumer nor the producer fully bears the costs associated with the transaction.

- Negative externalities can be categorized as technical externalities, which affect consumption and production opportunities, or pecuniary externalities, which impact financial gains without directly affecting production or consumption.

- Negative production externalities include air and water pollution from industrial activities, while negative consumption externalities involve harm caused to third parties by consuming certain goods, such as secondhand smoke from smoking.

- Market-based remedies like taxes, pollution permits, command and control approaches, and subsidies can be implemented to mitigate negative externalities. These aim to internalize the external costs and encourage more socially optimal outcomes in consumption and production.

- Each remedy has advantages and drawbacks, and the effectiveness of these measures depends on factors such as market conditions, government intervention, and stakeholders' ability to adapt to changes.

Mitigating negative externality

Externalities harm both those who produce them and those who consume them. Most production choices are based on financial data related to costs and revenues, with externalities often overlooked in cost assessments.

Unfortunately, social expenditures are frequently left out of cost assessments. As a result, the product may cause more harm than good to individuals around the production area.

Similarly, customers may fail to perceive the negative consequences of their actions, putting themselves and the people around them at risk.

Individual, household, and corporate consumption, production, and investment decisions may have indirect consequences, which, when aggregated, contribute to significant societal issues due to externalities.

Externalities arise when property rights over assets or resources are not efficiently allocated. For example, the overuse of resources, such as deforestation, overfishing, and transportation congestion, is also linked to a lack of property rights.

Note

Because so much of the environment cannot be protected by creating property rights, it is a finite resource that can be squandered at will. Recognizing the byproducts of negative externalities might help address issues affecting third parties and help policymakers develop practical solutions.

categories of negative externalities

Most negative externalities fall into the category of technical externalities. This is when the indirect impacts are on the consumption and production opportunities of others, but the price does not reflect the externalities that occur.

An example of a technological externality is the pollution that falls upon grapes in a winery. The winemaker can now produce less wine because the winery uses the same inputs (grapes) that were destroyed due to contamination.

Pecuniary externalities refer to actions taken by trading members that affect a third party's financial gains without directly impacting their ability to produce or consume.

Burger King, for example, will eat into McDonald's profits if it opens in a town where McDonald's also has a store. As a result, McDonald's suffers from a pecuniary externality.

Another example is if a technological innovation impacts workers' wages in a particular industry, such as the widespread adoption of self-checkout machines in supermarkets, which reduces the demand for (and thus wages of) cashiers.

In this case, there is a third-party effect, which also affects the valuation of a group's profit (labor wages), not its ability to produce. When we think of negative externalities, we usually think of technical ones. They are typically classified as either negative production or consumption externality.

Negative Production Externality

Negative production externality refers to the cost imposed on third parties by a firm or individual's production activity, for which they are not compensated.

An example might be when a steel firm generates air and water pollution during its manufacturing process, harming adjacent towns by contaminating their water or emitting large volumes of emissions into the atmosphere. Other examples could include the following:

1. Air pollution

Factory releases of harmful gases and toxins, such as carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, into the atmosphere can cause air pollution. These gases can harm various objects, including crops, buildings, and human health.

Air pollution also increases the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, accelerating the rate of global warming. All these effects adversely impact the current and future generations.

Note

Increasing air pollution contributes to rising sea levels, severe weather, reduced precipitation, and deteriorating air quality.

2. Water pollution

Harmful pollutants from industrial waste directly affect humans, animals, and crops that depend on public waterways to survive.

Toxins such as perfluorinated compounds (PCF) pose an extreme threat to crops and aquatic animals in a specific region, threatening the planet's biodiversity and disrupting the food chain.

This can directly influence the livelihoods of fishermen and farmers whose income depends on these species.

3. Farm animal production

Farm animal raising can impact adjacent third parties who live near the farm. Misuse of an antibiotic, for example, may result in a pool of animals with antibiotic-resistant bacteria that travels outside the farm, affecting the natural genetics of other animals.

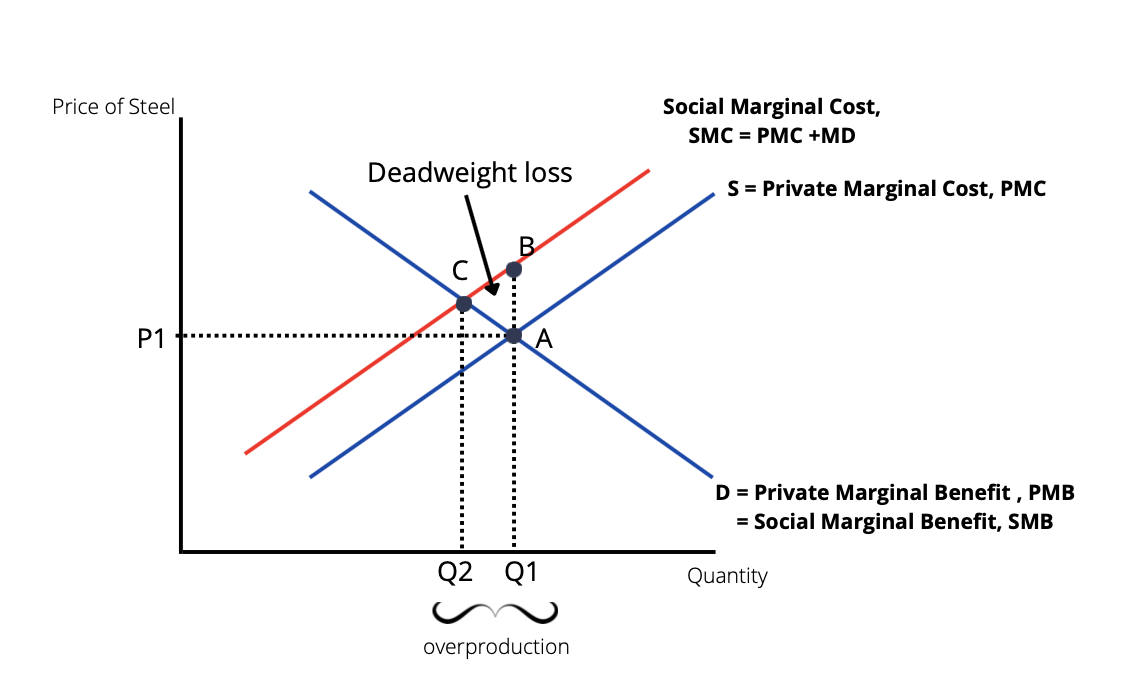

Methane emissions from animals such as cows contribute to global warming, which can indirectly impact human health and the environment. This is represented in graphical terms as shown below with the following notations:

- Private marginal cost (PMC): The direct cost to producers for producing an additional unit of good

- Marginal damage (MD): Any additional costs associated with the production of the good that is imposed on others but that producers do not pay

- Social marginal cost (SMC = PMC + MD): The private marginal cost to producers plus marginal damage

- Deadweight loss: The shaded area between A, B, and C shows a mismatch in market demand and supply

Assumptions are as follows:

- In a free market, the output is where the S(PMC) line intersects the D(PMB) line at point A, which Q1 denotes

- A free market assumes that individuals ignore external costs

For example, if you drive a car, you will only consider the cost of gasoline, not the consequences of traffic and pollution on others.

This diagram demonstrates that externalities outweigh private costs. As a result of these assumptions, we have overproduction. Instead, a socially efficient output level would be when SMC = SMB occurs in Q2. At this point, the overproduction would be reduced.

Negative consumption externalities

A negative consumption externality is when consuming goods harms a third party. For example:

- Smoking: Generates secondhand smoke and passive smoking to nearby individuals, affecting children's development if they are exposed for an extended period.

- Excessive alcohol consumption: This may result in greater drunkenness, increasing the risk of accidents or social disturbance.

- Noise pollution: Examples include loud music, which could disturb neighbors, leading to more complaints and disturbance.

- Traffic congestion: Causes significant delays as too many drivers are on the road. This can lead to disruption in traffic for all motorists during commuting time.

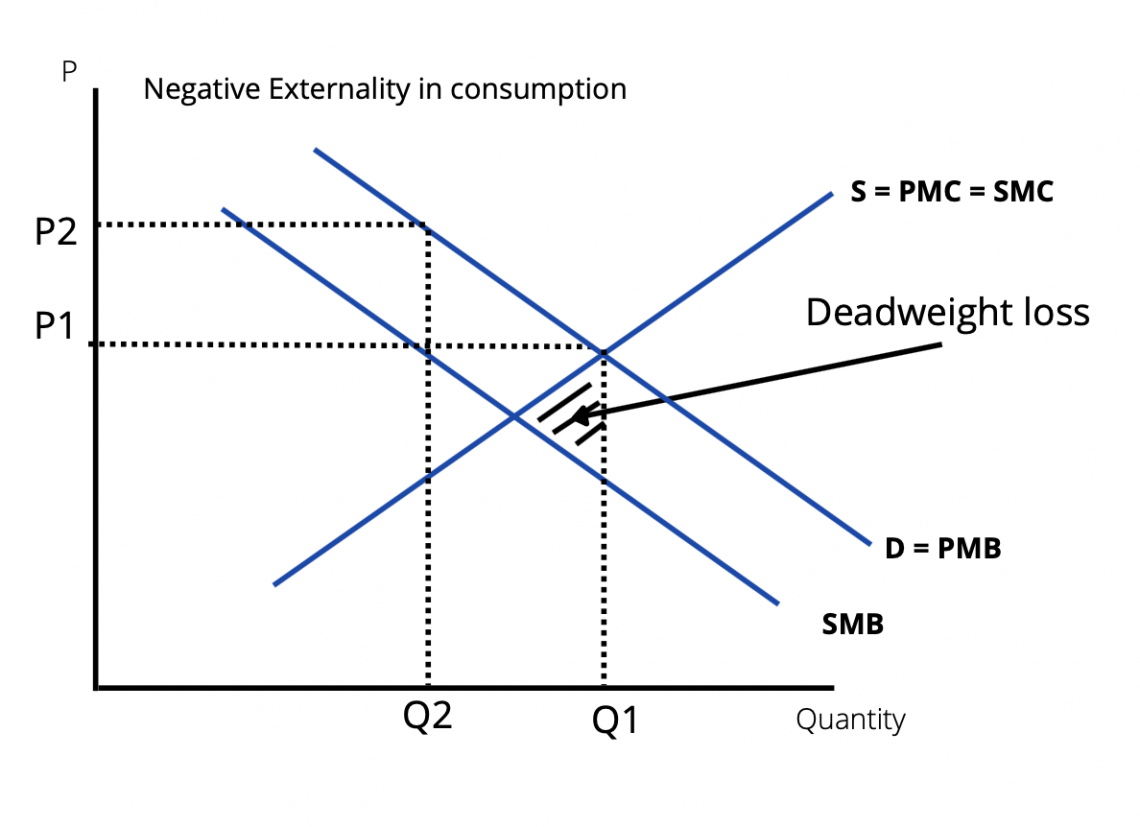

A negative consumption externality is shown in the graph below when SMC exceeds SMB with the following assumptions:

- In a free market, we get output at Q1, which is when SMC > than SMB

- The red triangle denotes the deadweight welfare loss

- The output will shift from Q1 to Q2, achieving a socially efficient output where SMB = SMC to correct this

deadweight welfare loss

Both diagrams illustrate the deadweight welfare loss as a shaded triangle. When output is at Q1, society experiences deadweight welfare loss due to market inefficiency.

Under free-market assumptions, the point at Q1 represents an unregulated market in which enterprises and individuals may produce and consume at inefficient and not socially optimal levels.

For example, a baker makes 100 loaves of bread but only sells 80. This results in more than 20 loaves. The remaining bread will get stale and moldy and must be discarded.

The deadweight loss disrupts the market's natural equilibrium, with customers losing out on potential demand or firms losing out on their potential revenue due to supply and demand allocation inefficiencies.

This is because deadweight welfare loss occurs when consumers and sellers do not bear inefficiency costs. Externalities may also contribute to deadweight welfare loss, but they are not the sole cause.

This indicates a mismatch between supply and demand. Various methods, such as taxes and subsidies, can address deadweight welfare loss.

Remedies for Negative Externalities

Market-based remedies such as environmental taxes and tradable permits can be imposed to pressure enterprises and individuals to adjust their behavior. This will lessen the deadweight welfare loss from overproduction and overconsumption.

Market-based solutions offer flexibility in finding solutions that improve resource allocation. These processes also cultivate innovation by promoting the notion that sustainability will become increasingly cheap over time.

This is achieved through subsidies and grants for R&D and innovation efforts.

Similarly, with society's increasing pressure to adopt stricter CSR initiatives alongside government incentives, firms will be more incentivized to upgrade their operations and differentiate themselves from their competition.

Note

It is also critical to consider how such measures affect the lower-income group to guarantee they do not suffer due to price increases.

When market solutions are implemented effectively, these approaches will reduce pollution at the lowest cost to society. Government agencies must monitor their policies.

This is done to guarantee that the costs and benefits of a policy are distributed fairly across groups and people. These remedies mainly involve government intervention, such as placing taxes, quotas, pollution permits, and subsidies. These will be discussed in the following sections:

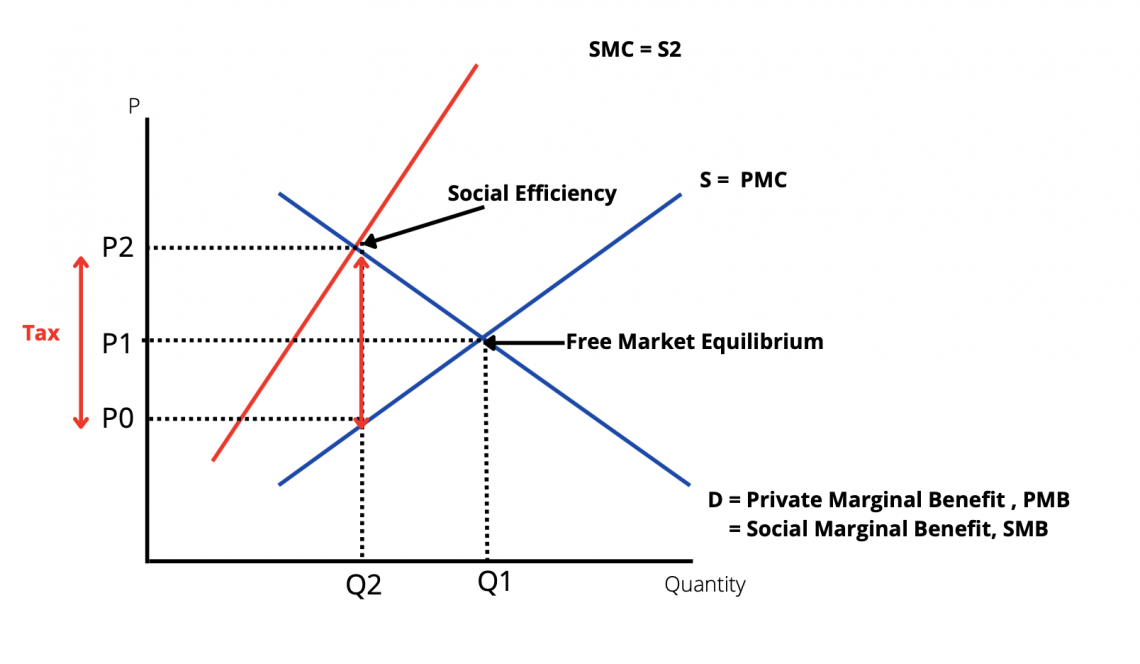

Taxes

Taxes have the potential to reduce consumption and the development of externalities. An effective tax rate equals the cost of the externality, requiring persons who want to consume or produce the product to pay the full social cost of the good.

Taxation effectively raises the cost of production and consumption by attempting to represent the actual cost of production, also known as spillover costs.

For example, alcohol taxes have been introduced to reduce the consumption of alcoholic products.

Other taxes include:

As stated previously, without taxes, there will be overconsumption in Q1. Now, with taxes, there are incentives to reduce negative externalities. The tax reduces output to Q2 on the diagram by pushing the price from P1 to P2.

Now, the market can achieve social efficiency where SMC and D intersect at Q2, P2.

The following evaluation points should be considered to determine the effectiveness of taxes:

- What is the effectiveness of a tax if the price elasticity of demand (PED) is inelastic?

- Will this tax affect lower-income groups? For example, if an energy tax is adopted, will the rise in energy prices significantly impact the lower-income group?

- What are the opportunity costs of collection for tax evasion?

These considerations raise the question of whether there are alternative ways to impose a tax.

Note

Taxes are also useful in assisting the government in raising revenue, which may subsequently be invested in other merit goods that benefit society, such as public transportation networks and healthcare.

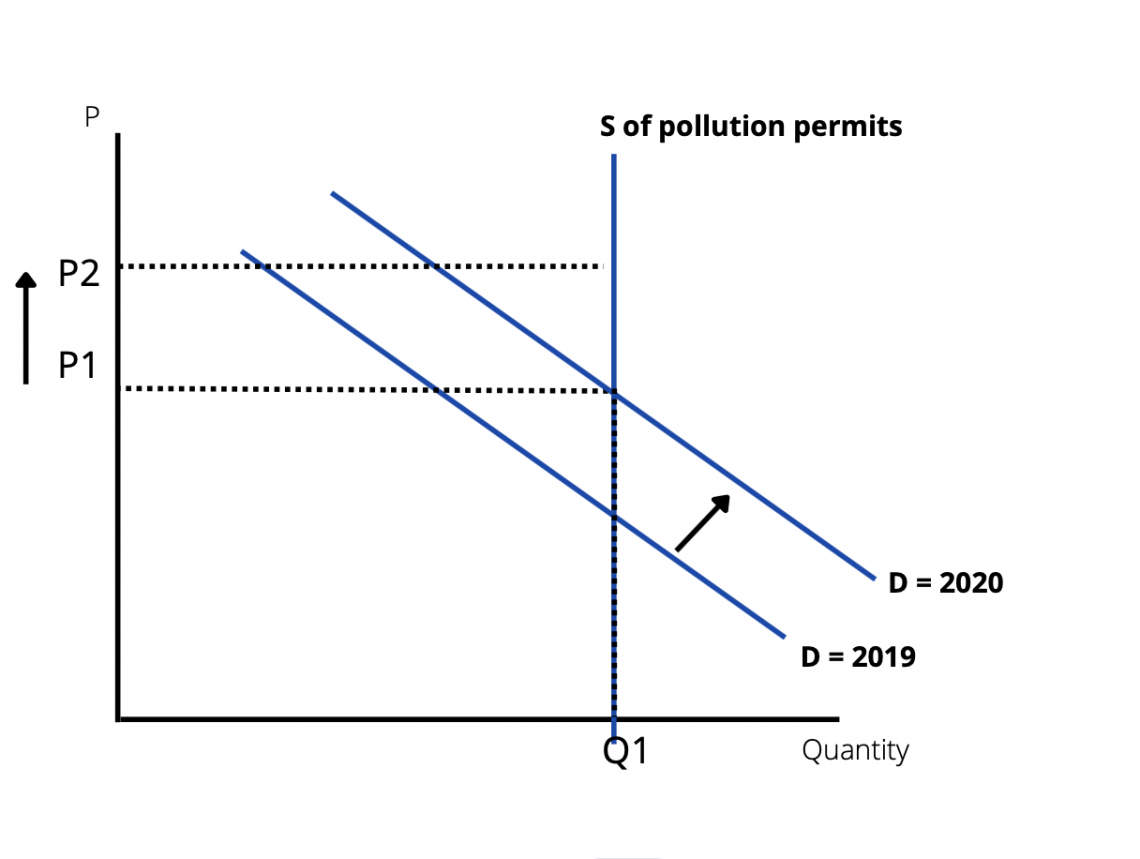

Pollution permits

Pollution permits, often known as carbon trading, give businesses the legal authority to produce specific amounts of carbon dioxide.

For example, if a pollution permit enables a company to emit 200 units of carbon dioxide per year, it can use the entire quota or a portion of it.

If the company pollutes less than the permit allows, it may decide to sell its permits to other businesses and vice versa. This eventually leads to a market for firms to buy and sell pollution permits.

As seen in the diagram, a fixed supply of pollution permits raises the cost of pollution. This will be effective if there is a sudden spike in pollution levels. This helps to minimize pollution by lowering incentives through price mechanisms.

Governments can reduce the supply of pollution permits, making them scarcer, to raise the price of pollution permits. These efforts make it more expensive for firms to emit carbon, which may stimulate a longer-term focus on alternative low-carbon technology.

Note

One critical point of contention regarding pollution permits is their efficiency in lowering harmful emissions. Monitoring pollution levels can be challenging, and there is a power imbalance between richer and poorer countries. More prosperous countries with greater polluting demands can purchase pollution permits, dumping emissions onto developing countries.

Command and control approaches

Command and control approaches are regulations the government imposes to reduce the production of negative externalities. These were especially prevalent in the US during the late 1960s and 1970s, when it started to pass environmental laws.

In effect, these policies increase the costs for firms by regulating the type of technology used, such as installing anti-pollution equipment, so that firms can consider the total social cost.

For example:

- The Health and Safety at Work Act applies to all businesses

- Renewable energy obligation certificates are being issued to stimulate the provision of renewable energy

- Introducing regulations governing how harmful commodities, such as automobile batteries, should be disposed of

- Vehicle manufacturers must follow strict rules to ensure that their systems meet carbon emission standards

- Quotas on fishing to protect wildlife from overfishing

- Setting a minimum age for the consumption of demerit goods

However, there are a few drawbacks to using the command and control approach:

- There is no incentive for firms to go beyond the standards set. Once these policies are satisfied, producers will not take the extra steps to improve

- Policies are often inflexible as the same standard needs to be applied to everyone. This means that command and control policies do not consider the ability to pay between a small or a large firm

- Since legislators and the Environmental Protection Agency write these policies, lobbying and the political process, affect specific policies

Subsidies

Subsidies are a common way for governments to promote research and development, encouraging businesses to employ safer technologies to produce goods and services.

The use of subsidies may be more beneficial than taxes as it is not a policy instrument intended to tax the poorer income group to address negative externalities. Instead, subsidies help to keep energy prices low for consumers while reducing the cost for producers.

Using subsidies helps alter incentives so individuals' decisions align with socially optimal allocations.

Subsidies also give consumers and producers more flexibility than traditional command and control approaches, as different amounts can be allocated to other business structures and needs.

Note

In agriculture, subsidies are provided to redevelop brownfield sites, erosion control, and loans to farmers.

Green farming technology, for example, can be implemented in the agriculture sector to produce organic products without pesticides or toxic chemicals that could leach into adjacent water systems or cause mutations in other plants.

Free Resources

To continue learning and advancing your career, check out these additional helpful WSO resources:

or Want to Sign up with your social account?