Dividend vs Share Buyback/Repurchase

Dividends and share buybacks are both ways for companies to return cash to their shareholders.

What is Dividend Vs Share Buyback Repurchase?

Dividend and share buyback (also known as share repurchase) are two common methods through which a publicly traded company can distribute its profits or return value to shareholders.

Investing money in a company makes you an investor and shareholder. Undoubtedly, one of your objectives is to generate high returns on your investment. How can companies pay you back and let you recuperate your return and money?

This is what we call a payout policy. It is a fancy word describing when a company returns money to investors. Payout policy can take two forms: dividends or share repurchases.

Considering dividends and share repurchases, they share something in common: companies are not obligated to pay out cash to investors. It is merely a choice.

Companies can pay dividends and buy back shares, or companies can do neither. For instance, Amazon has never paid dividends in its history. Coca-Cola has one of the most extended dividend histories. The choice depends on multiple factors and differences between the policies.

Historically, the share of buybacks in the payout policy has always been higher than that of dividends. Additionally, the proportion of companies paying dividends has decreased over time (1980-2018). In contrast, more companies shifted their gaze to buybacks.

Buybacks and dividends are a source of many polemics, and finance high flyers have various arguments in favor of one or another concept. For example, Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger are some of the most known supporters of stock repurchases.

Key Takeaways

- A portion of a company's profits distributed to shareholders is called dividends. The dividend payout ratio indicates the percentage of earnings distributed as dividends.

- Dividends can be viewed as a positive signal of a company's confidence in future earnings, but a dividend decrease can be seen negatively.

- Stock repurchases mean a company buys back its shares. The timing and number of shares repurchased depend on various factors.

- Share repurchases can be a sign of undervaluation and are often used to offset dilution from equity-based compensation plans.

- Repurchasing shares can also increase earnings per share and be used for earnings management.

The Dividend vs Share Buyback Debate

Even if paying dividends and buying back shares are the same principles regarding returning money to investors, these policies are wildly divergent. Their mechanics and consequences should be mastered to understand how companies are impacted by preferring one to another.

The same policy can be beneficial for one company but detrimental to another. Everything should be analyzed within a company's context to evaluate the possible fallout of a chosen approach.

Payout policies should concern you as a retail investor because they can influence your wealth. Here are three crucial considerations to keep in mind:

- The effect of taxes on your cash-in,

- The potential increase or decrease in the value of your investments

- Your investor's profile expectations and preferences

In closing, both policies merit to exist as they offer advantages most adapted to specific situations for companies and investors. Let’s take a look at payout policies in more detail now.

Exploring The Mechanics Of Dividends

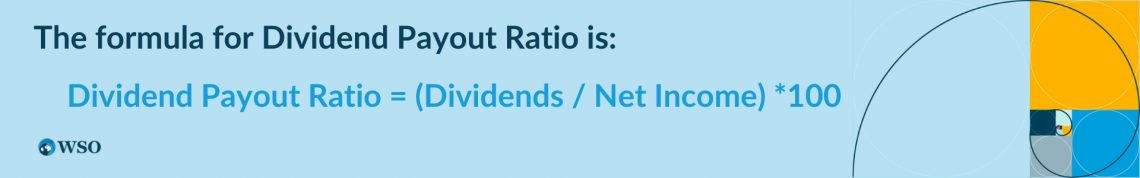

A dividend is a portion of a company's profits to its shareholders. Dividend payout is measured as:

The dividend payout ratio indicates how much earnings a company gives out in dividends to its shareholders. Let’s take an example. If a company’s net income is $1M and it pays out $0.5M in dividends, its dividend payout ratio would be 50%:

Dividend Payout Ratio = ($0.5M / $1M) * 100 = 50%

In reality, companies can even choose to pay more dividends than their total earnings in a single year. A dividend yield is another measure of determining how attractive an investment could be. It is computed as:

Dividend Yield = (Dividend Per Share/ Share Price) * 100

The higher the dividend yield, the higher investors’ remuneration is. Rarely do dividend yields exceed the 5% mark.

Dividends can be considered something good or bad depending on a view. Some investors prefer dividends because they are certain, unlike capital gains on stocks.

When companies start to pay dividends, investors expect them to be sticky. This move is often perceived as a company’s confidence regarding its future earnings.

It means that subsequent dividends should grow or remain at least at the same level. If a company engages in paying dividends, it should be persistent. Failure to do so will undermine investors’ trust.

When a company increases its dividends, it sends a positive signal to the market. On the contrary, a decrease in dividends is a bad signal. In November 2017, General Electric announced a dividend cut of $4 billion, consequently resulting in a significant share price drop.

Note

A cut in dividends is not always viewed as negative. Companies may channel saved money to more business-oriented strategies to create better long-term value and bolster their core lines.

Capital gains or share price appreciation is not something every stock can experience. Sometimes, their price goes up, and sometimes it goes down. Therefore, risk-averse investors prefer dividends since they are inherently not subject to losses.

However, this argument has a drawback. In practice, the share price drops after paying out dividends approximately by their amount. Thus, existing shareholders have a capital loss.

Capital loss implies that your asset’s price has decreased. Consequently, if you immediately sell the stock, you will incur a loss equal to the amount of the share price decrease.

Note

Your total wealth remains unchanged since you receive a dividend in cash, offsetting your capital loss. So why does the share price decline?

A new investor wishing to enter this investment would not be willing to pay the total price (ex-ante dividend distribution) because this asset has just distributed some money.

The perceived immediate value of purchasing the asset at its current price might be diminished for new investors, as they would not receive the full benefit of the recent distribution.

To attract new buyers, a discount is necessary, acknowledging that the asset has already generated income and may be less appealing at its current price.

Example Of Dividends

Dividends are paid out to all shareholders whether they want it or not. Being a shareholder, you can’t renounce receiving a dividend except by selling your shares.

An investor should conduct a thorough analysis to gauge the interest in receiving or not dividends.

Consider this:

- Price paid for a share = $20

- Price before a share goes down due to dividends distribution = $22

- Price after dividend announcement = 19$

- Dividend = $3

Let’s take for our first scenario a tax rate of 30% for capital gains and 40% for dividends.

We need to compare the total gains of an investor when he:

- Sells his share before dividend distribution

- Sells his share after dividend distribution

Note

Dividends don’t affect the number of shares, unlike buybacks. It is intuitive because the goal is to attribute some money to each existing share.

Selling before dividend distribution entitles him to a capital gain of $2:

$22 - $20 = $2

These $2 are taxed at 30%, yielding a net gain of $1.4. Now, selling a share after dividend distribution pays a dividend of $3, taxed at 40%, and a net gain of $1.8. There is also a capital loss of $1 due to the sale of the share at $19 vs. $20 purchase price.

Therefore, the total net gain is

$1.8 - $1 = $0.8

In this scenario, selling a share before a dividend distribution is preferable to seek higher benefits.

What if we change tax rates? Let’s now assume a tax rate of 70% on capital gains. This will give a net profit of $0.6 due to the price appreciation if you sell your share before the dividend distribution.

In such a case, holding this share will generate more money for an investor as dividend taxation is less harmful to your wealth than capital gains taxation.

Stock Repurchases

A stock or share repurchase is when a company buys back its shares from its shareholders, paying a current trading price to sellers. This process is meant to create value in the company’s shares because it reduces the total number of shares outstanding.

A reduction in the number of shares means that the share price will rise, ultimately stimulating an increase in the company’s shares of stock.

Note

This increase in the stock price after a share repurchase is usually not an accurate representation of the company’s value since it is an artificial influence on the share price.

Share repurchase may be a sign of undervaluation in the company. Managers might expect shares to go up in the future, so buying them at a lower price today is a good deal.

However, evidence shows that stock buybacks are usually used to offset dilution or when shareholders own a lower percentage of the company due to an increased number of shares outstanding.

In fact, it is frequent to observe share repurchases when share prices are high and not low. Now, the company can do two things with the purchased shares:

1. Keep them for a later re-issuance of shares

In this case, the shares can be put back on the market or given to employees in a compensation package.

Companies frequently provide stock options or grants to compensate their employees as a component of their overall remuneration plans.

Note

The company can counterbalance the potential dilution resulting from these equity-based compensation initiatives by repurchasing shares.

2. Retire the shares

When retiring shares, the company must buy the shares and cancel them. This means that the shares would no longer have any financial value or ownership over them.

A company could retire shares to preserve share prices, make its ratios more attractive, and prevent external factors from influencing the public company’s success.

Unlike dividends, share buybacks don’t need to be sticky. A company can initiate this policy whenever it is deemed necessary.

The timing and number of shares repurchased depend on various factors like

- Price

- General business

- Market conditions

- Alternative investment opportunities

As you may know, stock repurchases reduce the share count and increase leverage. Since stocks constitute equity, their diminishing will attribute more weight to the debt in the capital structure. This move can be particularly effective if a company is underleveraged.

One of the interesting principal advantages of this repurchase policy is that investors have freedom of choice. They can sell their shares to the company, or they can also opt to hold them.

Another use of repurchases is linked to earnings management if a CEO’s compensation is tightened to EPS (earnings per share). Repurchasing shares mechanically increases EPS (Earnings / Shares outstanding).

Nevertheless, this is a controversial practice, and manipulating executive compensation targets or misleading investors can result in legal and ethical issues.

As mentioned previously, increases in important financial ratios could spark investors' interest, making a company more attractive due to a repurchase plan.

Thus, if a top company’s manager can’t achieve the target EPS to cash in his bonus, he can manipulate this buyback to “get it done.”

or Want to Sign up with your social account?