Market Cycle

Patterns or trends that develop in different markets or economic contexts

What is a market cycle?

The market cycle, often known as the stock market cycle, is a general term that refers to patterns or trends that develop in different markets or economic contexts.

Because their business models are compatible with growth conditions, some securities or asset classes do better than others during a cycle.

The distance between two successive highs or lows of a standard benchmark is what this measure means, which demonstrates how well a fund performs in up and down markets.

Proponents of the theory contend that the stock market exhibits hypothetical patterns known as stock cycles.

Many other cycles have been proposed, such as connecting market volatility to political leadership or commodity price fluctuations.

Some trends in the stock market are generally acknowledged (e.g., rotations between the dominance of value investing or growth stocks).

On the other hand, many academics and experienced investors are dubious of any theory that claims to be able to detect or anticipate the stock cycle accurately.

External variables such as the United States monetary policy, the economy, inflation, currency rates, and social circumstances all influence stock returns (e.g., the 2020-2021 covid virus pandemic).

The present earnings of a company's shares are affected by intellectual capital. The return growth of a stock is aided by intellectual capital.

Except for substantial supply shocks, economist Milton Friedman thought that company losses are mostly a monetary phenomenon. Despite the term cycle's common use, corporate economic activity changes do not follow a consistent or predictable pattern.

According to traditional theory, a fall in price will result in less supply and greater demand, whereas a price rise will have the opposite effect.

This works well for most assets, but it frequently works in the other direction for stocks since many investors buy high in euphoria and sell low in fear or panic due to the herding impulse.

If a price rise creates an increase in demand or a price fall causes an increase in supply, the predicted negative feedback loop is broken, and prices become unstable. This might be observed in the form of a bubble or a crash.

Key Takeaways

- The market cycle, or stock market cycle, refers to recurring patterns or trends observed in various markets or economic environments.

- Different securities or asset classes perform differently throughout a cycle, depending on how well their business models align with prevailing growth conditions.

- Performance during market cycles can be measured by the distance between successive highs or lows of a benchmark, indicating how well a fund performs in both up and down markets.

understanding the Market Cycle

It refers to the economic trends in many different business contexts.

During an upcycle, a company's revenue and profitability may see a rapid increase and stagnation or downtrend in the top and bottom lines during a downcycle. Temporal patterns can be seen in companies working within a particular industry. These patterns are cyclical.

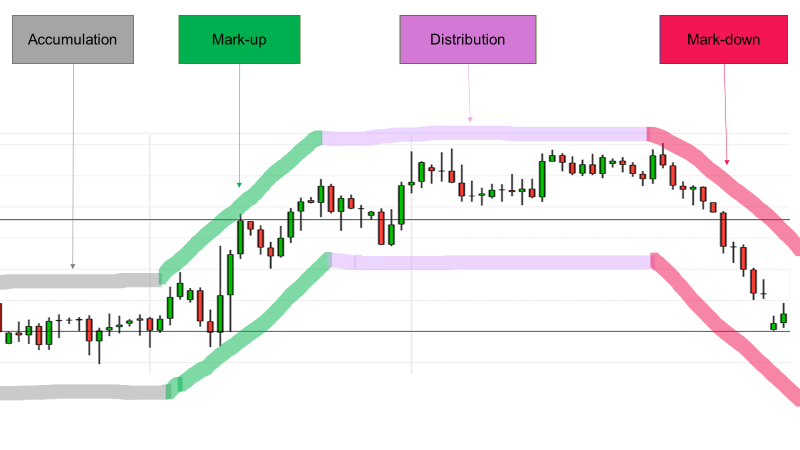

The four stages of a stock cycle are:

- Accumulation

- Markup

- Distribution

- Markdown

A new cycle is born when a new technology breakthrough or a change in market rules upsets existing market patterns and produces new ones.

Hence, with the introduction of new goods or a new regulatory regime, the shift is industry-specific, which means that it may or may not affect the market as a whole.

It considers fundamental indicators, such as interest rates, asset prices, and industrial output, among other things.

New cycles emerge when real innovation, new goods, or the regulatory environment create disruptions within a single sector.

Revenue and net profits may show similar growth patterns among numerous firms within a particular industry throughout these upcycle periods.

It's sometimes difficult to determine until after the fact. They seldom have a different starting or end point, leading to misunderstanding or debate when evaluating policies and initiatives.

On the other hand, most market veterans think they exist, and many investors follow strategies aimed at profiting from them by trading securities ahead of cyclical directional shifts.

Anomalies in the stock market can't be explained, but they happen yearly.

It can last anywhere from a few minutes to several years, depending on the market and the studied time horizon.

Different occupations will examine various components of the spectrum. For example, a real estate investor would be interested in a cycle of up to 25 years, but an intra-day trader might be interested in ten-minute bars.

Market Cycles Types

Market cycles can be categorized into different types based on their duration.

The divisions can vary depending on the source and context, but there are standard ways based on which the market cycles are divided:

1) Secular or Long-Term Cycles (10-20+ years)

These are the most extended market cycles that typically span decades. They encompass multiple economic and market cycles and are often influenced by structural economic shifts, demographics, and technological advancements.

Secular bull markets are characterized by extended periods of rising prices, while secular bear markets involve prolonged periods of declining or stagnant prices.

2) Business or Economic Cycles (2-10 years)

Business cycles are medium-term and usually span several years. They are characterized by alternating periods of economic expansion (growth) and contraction (recession).

These cycles are driven by factors such as changes in interest rates, consumer spending, business investment, and government policies.

3) Kitchin or Inventory Cycles (3-5 years)

Named after economist Joseph Kitchin, these cycles typically last around three to five years and are associated with fluctuations in business inventories.

When inventories are high, businesses may reduce production and investment, leading to a contraction. When inventories are low, companies ramp up production, leading to expansion.

4) Juglar or Fixed Investment Cycles (7-11 years)

Named after Clement Juglar, these cycles occur roughly every seven to eleven years. They are tied to fixed investment fluctuations, including business capital expenditures on equipment and infrastructure.

Changes can influence these cycles in interest rates and credit availability.

5) Seasonal Cycles (1 year or less)

Seasonal cycles repeat within a calendar year and are often related to natural events, holidays, and other seasonal factors. For example, the holiday shopping season can impact retail stocks, and agricultural commodities often experience price fluctuations based on planting and harvesting seasons.

6) Short-Term Cycles (weeks to a few months)

These cycles can be driven by market sentiment, short-term economic indicators, and trading patterns.

Technical analysis and short-term trends often play a more significant role in these cycles, and news events and macroeconomic data releases can highly influence them.

While these cycle categories can provide a framework for understanding market movements, they can overlap or vary in duration due to changing economic conditions, external events, and other factors.

Traders and investors often use a combination of fundamental analysis, technical analysis, and market research to identify and respond to various market cycles.

Different Phases of a Market Cycle

These cycles are said to be divided into four main periods. Different securities will react to market dynamics differently at other points of a whole market cycle.

For example, luxury products excel during a market upswing because individuals feel more comfortable buying powerboats and Harley Davidson motorcycles.

During a market downturn, on the other hand, the consumer durables business tends to succeed, as individuals don't usually cut back on their toothpaste and toilet paper usage.

The four stages are the accumulation, uptrend or markup, distribution, and downturn or markdown phases.

In general, there are four stages. At each step, securities will react to market conditions in a particular way. Companies are selling luxury goods, for example, increasing rapidly during an upswing or a boom time.

The fast-moving consumer goods industry (FMCG) is projected to excel during a downturn or recession. This is because demand for basic needs and consumer durables such as food and hygiene goods remains stable.

The following are the four stages:

Phase 1: Accumulation

The accumulation begins as soon as the market reaches its lowest point. Value investors, money managers, and experienced traders begin buying shares after they believe the worst is gone, and values become critically important.

This is known as accumulation, when investors and corporations re-enter the market and increase their exposure.

The market attitude shifts from negative to neutral over this time frame. The market, though, remains negative.

After the market has bottomed, innovators and early adopters continue to buy, believing that the worst is behind them.

Phase 2: The markup stage

During the markup stage, investors begin to pour in big amounts of money, resulting in a significant increase in market volume. However, while stock prices rise above historical norms, unemployment and layoffs continue to grow.

At the markup stage, market attitude shifts from neutral to positive and, in some circumstances, exuberant. Finally, a selling climax is witnessed due to the participation of fence-sitters and reluctant or risk-averse investors, which is a last parabolic price surge.

Mark-up Phase is when the market has remained steady for a time and then begins to rise in price.

Phase 3: Distribution

The third cycle is the distribution phase, during which traders begin selling securities.

The market's mood shifts from optimistic to neutral. It is when the market shifts direction at the end of a term.

On the other hand, distribution is a time when investors begin to reduce their exposure to their investments.

The change is gradual and may take a long time to complete. Over several months, prices tend to remain relatively stable. However, a sudden unfavorable geopolitical upheaval or terrible economic news, such as pandemic lockdowns, may hasten the process.

In the distribution phase, sellers begin to dominate as the stock reaches its top.

Phase 4: The markdown stage

The final part of a cycle is the markdown phase, which is disastrous for investors who still retain equities. Security values had plummeted much below what investors paid when they bought them.

As this is the last period, it also signals the start of the next accumulation phase, in which new investors will buy discounted assets.

It uses securities prices and other measures to gauge cyclical activity, considering both fundamental and technical indications.

The business cycle, semiconductor or operating system cycles in technology, and the movement of interest-rate-sensitive financial equities are just a few examples.

Market Cycle FAQs

It endures between 6 to 12 months on average. On the other hand, fiscal policy in the United States or global markets may have a broad impact on the length of a market cycle.

The average is 6 to 12, but if the Federal Reserve, for example, were to significantly lower interest rates, a market heading higher might be extended for years.

When an economy is robust but growth is slowing or moderating, it is called a market mid-cycle. Corporate earnings are on track, and interest rates remain low. This is the stage of the market cycle that lasts the longest.

Since there is no discernible beginning or conclusion to a stock cycle, predicting a cycle is nearly impossible.

On the other hand, it is possible to estimate at what stage of the cycle a particular sector or industry is looking at the fundamental indicators like output, demand, interest rates, margins, etc.

It has no predetermined duration, meaning it can run for any time - from a few days to a decade. As a result, it can potentially obstruct economic and monetary policy formation.

One's point of view usually determines the length. For example, options traders may be interested in price swings over 5-minute bars, but oil investors may be interested in a longer cycle of roughly 20 years.

Many major institutional investors and individual investors seek to predict the future as a transition ahead of time.

They may be able to profit from the cycles and take good bets as a result of it. It is the fundamental premise of financial speculation.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?