Theta

It represents how much an option's premium may decay daily, with all other factors remaining the same.

What Is Theta?

Theoretically, theta (Θ) represents how much an option's premium may decay each day, with all other factors remaining the same.

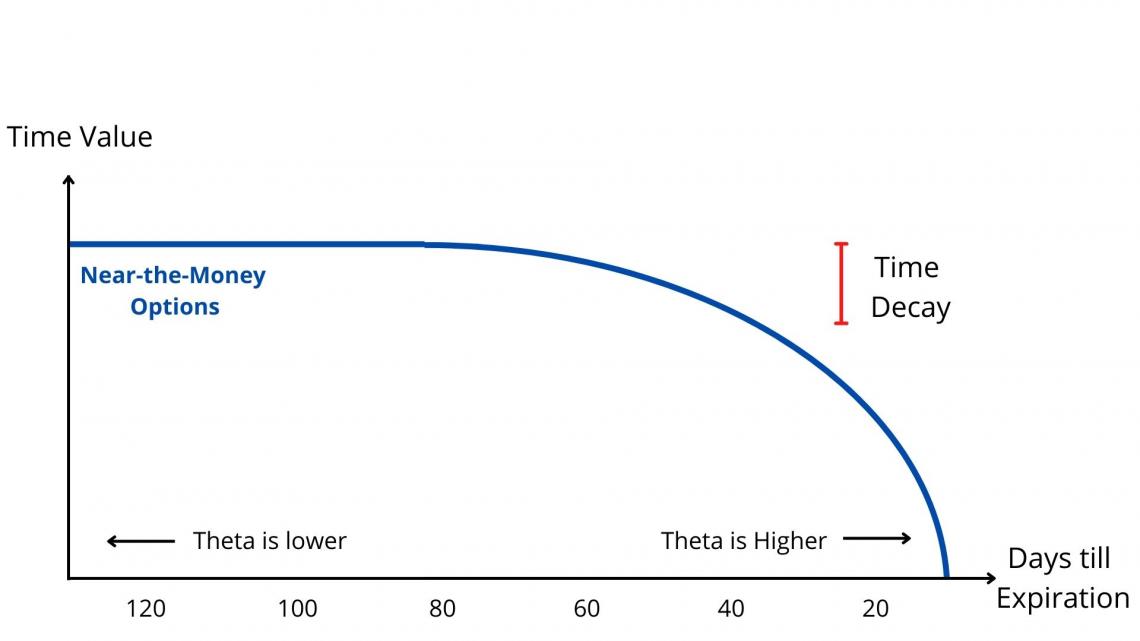

Options lose value over time. The moment the contract is created, the time value begins to deplete. As the expiration date approaches, the loss in the time value of near-the-money options accelerates. Below is a representation of its nonlinear nature.

A higher theta indicates that the option's value will decay more rapidly over time. Especially near-the-money (approximately breakeven), it is typically higher for short-dated options, as there is more urgency for the underlying to move in the money before expiration.

It is a positive value for short (sold) positions and a negative value for long (purchased) positions – regardless of whether the contract is a put or a call.

As it is always negative for long options, the time value will always be zero when the option expires. This is why it is a good thing for sellers but not buyers, as the value decreases from the buyer's side as time goes by but increases for the seller.

That is why selling an option is also known as a positive theta trade—as it accelerates, the seller's earnings on their options increase.

Long Options and Theta

A long option holder’s position has a negative Theta, which equates to buying time. Since time is constantly depleting, a long option holder’s likelihood of experiencing a positive price movement is also constantly depleting. Therefore, the positive price movements must be greater than the effects of Theta.

Essentially, holding an option to expiration is only profitable if the underlying moves are more significant than the Theta purchased. Otherwise, It can be captured by closing the option before expiration.

For example, if XYZ is trading at $100 and an XYZ $100 call is purchased at $3, the premium is primarily time value, as executing the contract is not more favorable than the market.

If XYZ remains at $100 at expiration, the call will expire worthlessly. The XYZ $100 call buyer will lose all the premium spent since the time is up.

If XYZ were at $105 on expiration, the XYZ $100 call would now most likely be worth $500, as an options contract usually represents 100 shares. This profit would be reaped by buying at the strike, $100, and selling at the market price, $105, 100 times.

The loss in this scenario is limited to the premium paid and has unlimited reward potential.

Negative Theta typically means time is not in your favor. However, the risk is limited to an unlimited potential profit.

Note

Buyer Beware:

Since options are decaying in value, time favors the seller. The buyer needs price movement to tip the scales.

Short Options and Theta

A short option seller’s position has a positive theta, which equates to selling time. The cheaper the option will become as time depletes, working in the seller's favor.

The option seller can capture profit if the underlying is neutral, bearish (short call), or bullish (short put).

For example, if XYZ is trading at $100 and an XYZ $100 call is sold at $3, the premium is primarily time value. This is because executing the contract is not more favorable than the market.

If XYZ remains at $100 at expiration, the call will expire worthlessly.

The XYZ $100 call seller will keep the premium since the time is up. If XYZ was at $105 at expiration, however, the XYZ $100 call would now be worth at least $500, as the contract is more favorable than the market (buy at the strike, $100, and sell at the market, $105, 100 times).

The loss in this scenario has unlimited potential, and the reward is limited to the premium sold.

Positive value typically means time is in your favor; however, the reward is limited with infinite risk potential.

What are other factors to consider?

Some of the other factors are:

1. Decay Rate

Out-of-the-money options decay faster than in-the-money options.

This is because the deeper an option moves in the money, the more it moves toward a delta of -1 or +1, and the less meaningful the time value is for the option's value.

Delta measures an option’s value correlation to the underlying; the larger the number, the more correlated an option’s price is to the underlying asset(s).

In other words, in-the-money options will generally have a lower value.

Out-of-the-money options' prices will decay faster as they are composed mostly of time value. Therefore, a higher value depicts a higher decay rate.

2. Theta Absolute Value

All theta is not the same. It increases with at-the-money options and decreases with in-the-money options and out-of-the-money as expiration nears.

At-the-money options are likely to be barely above or below the strike as they are closer to the underlying price.

In-the-money options begin pricing mostly intrinsic value at expiration, and deep-in-the-money contracts lose their time value.

Out-of-the-money options are less likely to be above or below the strike as they have less time value closer to expiration.

3. Premium

An option's premium comprises extrinsic and intrinsic value. Time value and implied volatility are attributed to an option's extrinsic value.

How is Theta Calculated?

When the value of a long position on an option falls, it is closer to maturity, which shows an inverse relationship. Generally, on an option, for long positions, it is negative, and for short positions, it is positive.

It can be calculated using the following formula:

Θ=∂V/∂t =−∂V/ ∂t

Where:

- ∂ – the first derivative

- V – the option’s price (theoretical/extrinsic value)

- τ – the option’s time to maturity.

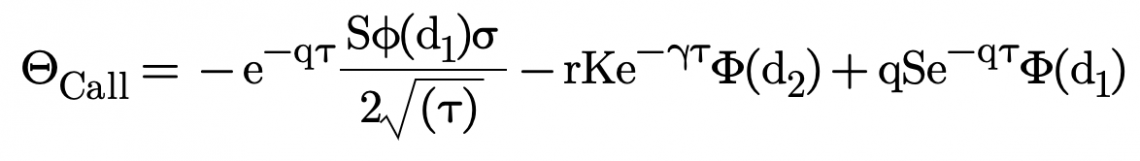

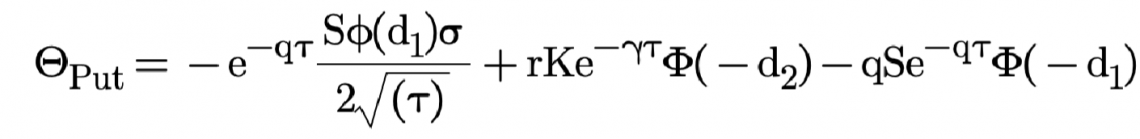

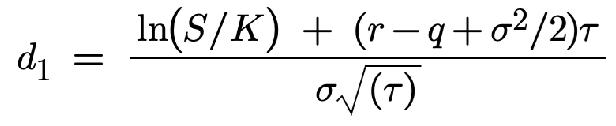

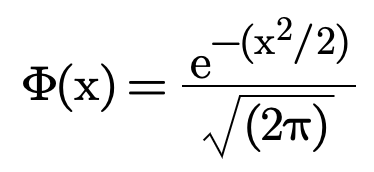

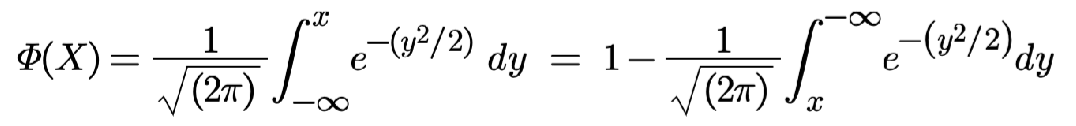

Under the Black-Scholes model, the calculation is given by:

Where,

Here,

- C = price of a call option

- P = price of a put option

- S = price of the underlying asset

- X = strike price of the option

- q = the annual dividend yield

- r = rate of interest

- τ = time to expiration

- K = the strike price

- σ = volatility of the underlying

N represents a standard normal distribution with mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1

It is expressed as a yearly value. However, to arrive at a daily rate, the figure is often divided by the number of days in a year. The daily rate refers to the amount the value will drop by per day.

A theta of -0.10 means that the price of an option would fall by $0.10 per day. However, it doesn’t mean that, in two days, the option price would have fallen by $0.20. This is because it changes daily.

It is important to note that it is not constant over the option's lifetime. As an option moves closer to its expiration date, it increases, and the value lost to time decay picks up.

Researched and authored by Rohan Kumar Singh | LinkedIn

Free Resources

To continue learning and advancing your career, check out these additional helpful WSO resources:

or Want to Sign up with your social account?