Securitized Debt Instruments

Individual loans (debt) are put in a pool of loan and then securitized to form financial securities known as securitized debt instruments.

What are Securitized Debt Instruments?

Debt Securitization is the process in which certain kinds of financial assets are grouped into pools to be repackaged into interest-bearing securities.

This process is a diversified and alternative source of financing based on the transfer of credit risk from issuers to investors.

These 'securities' are convertible, interchangeable, and negotiable financial instruments with monetary value.

The security can represent company ownership in the form of a stock or relationship with a government body or corporation through ownership of the entity's bond.

The interest and principal payments that come as a result of buying these assets are then passed through to the purchaser of the securities.

Key Takeaways

- Debt is issued to increase a company's capital. The debt must be repaid, often with interest added to the initial investment amount.

- The way debt has been issued over time has grown increasingly complicated as individual debt obligations have become pooled together and sold as interest-bearing securities. It started with the US Government's housing agenda.

- Pros of securitizing include lowering borrowing costs, minimizing liabilities, and offloading the risk of owning debt obligations.

- Cons of securitizing include the dilution of a quality portfolio of assets, the scale required to execute this investment type successfully, and the costs & fees involved.

- After the 2008 crisis, the industry was forced to greatly increase regulations and laws and strengthen governing bodies.

What are Debt Instruments?

Debt instruments are assets that require a fixed payment to the asset holder, typically requiring interest payment. These assets are sold to raise capital or generate investment income. Debt instruments include government bonds, corporate bonds, mortgages, and loans.

A debt instrument acts as an IOU between the debt issuer and the buyer. The buyer essentially lends money to the issuer by providing a lump sum. In exchange, the issuer guarantees a full repayment plus interest for the investment.

Bonds are the most common debt instrument. However, issuing bonds creates an obligation for the bond issuer, creating contractual interest payments that must be paid back to the purchaser.

Bondholders do not gain ownership in the business nor have any claims on the company's future profits. The bond issuer's only responsibility is to repay the loan through interest payments.

If the Government or corporation encounters financial troubles, the bondholder has senior, or first, priority in receiving payment, even over operational expenses.

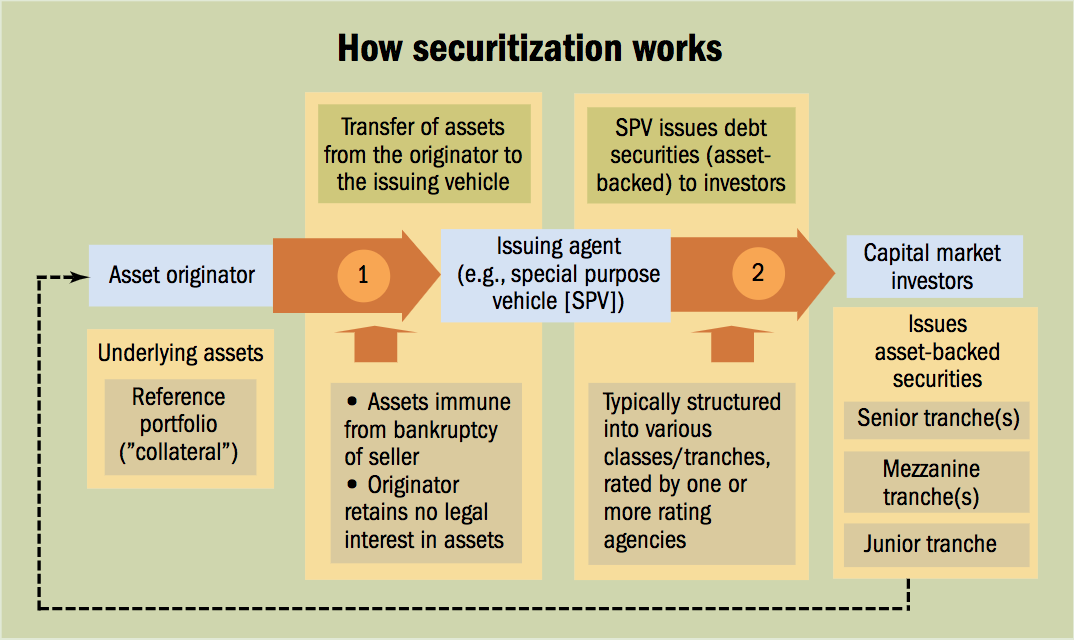

The Securitization Process

This process of turning these singular assets into a pool of securities is called the securitization process. To simplify the process, there are two steps:

Step 1

A company that owns loans or other assets that generate income, called the originator, identifies the assets it wants to remove from its balance sheet, pooling them together into a 'reference portfolio.'

The company then sells this pool of assets to an issuer, such as a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). In addition, a financial institution often creates this entity to buy the asset pool and recognize its off-balance sheet treatment.

Step 2

The issuer finances the acquisition of these pooled assets by issuing tradeable and interest-bearing securities sold to capital market investors.

The investor receives fixed or floating rate payments from a trustee account, funded by the cash flows produced by the portfolio of assets.

Generally, the originator services the loans in the portfolio, collects payments from the original borrowers, and passes them through directly to the SPV or trustee, often charging a servicing fee.

Note

Around the era of the 2008 financial crisis, the reference portfolio of pooled assets was divided up further into tranches, or subgroups, each having a different risk profile and sold separately.

Each tranche has a different level of seniority regarding its investment return and potential losses.

For example, the least risky tranche, called 'Tranche A,' is very stable, prioritizing the income generated by the asset pool.

The riskiest tranche, let's call 'Tranche D,' has the last claim on the asset's income and, therefore, is the more risky investment.

A typical structure has three tiers of tranches – senior, Mezzanine, and junior, in descending order of priority.

- The senior position expects to own a stable investment and has the lowest returns out of the three.

- The Mezzanine is in the middle of the road, not the most stable nor the least stable. These holders expect average returns accompanied by average risk.

- The junior position holds the first loss position in the portfolio. It is the smallest and riskiest tranche, bears the most credit exposure, and receives the highest return if all goes smoothly.

Common Instruments Used in Securitized Debt Instruments

Several instruments are used to create Securitized Debt Instruments and phrases and statements commonly abbreviated and used in conversation. With so many abbreviations out there, below are some of them broken down and explained:

1. Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS)

Securities in which these transactions are backed by mortgage loans, which can be residential or commercial:

- Residential MBS (RMBS)

- Commercial MBS (CMBS)

2. Asset-Backed Securities (ABS)

Assets that produce stable cash flows and can be structured into reference portfolios, supporting securitized debt.

Note

Mortgages, corporate loans, consumer credit, project finance, and individualized lending agreements can back these securities.

3. Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO)

It assumes the same structuring technology as the ABS but includes a wider and more diverse range of assets.

- Collateralized Bond Obligation (CBO)

- Collateralized Loan Obligation (CLO)

- Collateralized Mortgage Obligations (CMO)

4. Credit Default Swaps (CDS)

A less common instrument, this is a financial derivative allowing an investor to offset or swap their credit risk with other investors. It is an insurance mechanism as protection against defaults.

5. Securitized Financial Products (SFP)

Another term for pools of assets that make up a security that is split up and sold to investors.

6. Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV)

This is a subsidiary, or separate entity, of the company offering the investment opportunity, effectively isolating the financial risk.

As a legally separate company, it secures obligations to the investors if the parent company has financial issues such as bankruptcy.

- Special Purpose Entity (SPE)

History of Debt Securitization in the US

The principles of securitization first emerged in the 19th century, which included farm railroad mortgage bonds in the 1860s, mortgage-backed bonds in the 1800s, and a variation of mortgage securitization that preceded the Wall Street crash of 1929.

However, the modern era of this process truly emerged in the 1970s. In 1970, the US Govt began pooling home mortgages together.

The Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA or Ginnie Mae) sold these portfolios as securities. Ultimately orchestrated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, this was the first modern mortgage-backed security.

This event occurred due to post-war American culture, where the overarching sentiments of the American Dream and owning single-family housing in groomed neighborhoods led to policy changes within the Government.

Specifically, the US sought ways of increasing liquidity in the mortgage market. As a result, Ginnie Mae, created due to the Fair Housing Act of 1968, issued the first residential mortgage-backed security in 1970. They grouped mortgage loans and granted them as collateral for securities sold on the secondary market.

This aimed to gain investment dollars from global investors so America had more funding for affordable housing.

Congress also passed the Emergency Home Financing Act in 1970, which created the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac or FHLMC). This Act helped the institutions regulate interest rate risk by purchasing mortgages from them.

This Act also allowed these federal corporations to buy and sell mortgages insured/guaranteed by the Federal Government. This 1970 Act significantly expanded the secondary mortgage market.

- 1971 - Freddie Mac issued the first conventional loan securitization

- 1977 - Bank of America issues first private label residential mortgage pass-through bond

Fast forward to the 1980s, when the securitization of assets became increasingly sophisticated, the market continued to expand into other assets, such as Auto loans and Credit Card debt.

Note

Securitization vehicles became increasingly unregulated as they appeared off the balance sheets.

The securitization market exploded in the late 80s and 1990s. This was due to a combination of regulations pertaining to Mortgage Investments within the US and SEC rules changing, as well as several types of funds and institutional investors experiencing rapid growth and search for products.

Commercial and subprime mortgages (tranches) began securitizing in the 1990s. Global consumer culture, where access to credit was a guarantee, catalyzed growth in the volume of securitizations.

Note

Unregulated players began to enter the market, which loosened lending standards.

The booming industry came crashing down in the great financial crisis of 2008, which exposed the flaws in the entire system, including predatory lending practices, lack of regulation in the markets, consumer debt, and the rapid deflation/inadequate valuation methods of housing prices.

Lessons from the Crisis: The aftermath of the crisis was profound. Large institutions failed, countless deals defaulted, bankruptcies ensued, lawsuits emerged from investors, and regulators began proposing regulations to address the collapse's many facets.

Pros of Securitizing

Debt securitization rapidly grew for a good reason; it provided a lot of benefits for Institutional Investors with little downside. The pros vastly outweighed the cons until the 2008 financial crisis, where flaws were ultimately unearthed.

Despite the major event in 2008 that exposed this system, it is still an extremely smart way of accumulating investment dollars.

Below are several reasons why Debt Securitization grew to be so widespread and a major vehicle of success for both large and small investors:

- It reduces corporations' borrowing costs and lowers banks' regulatory minimum capital requirements.

- With a pool of assets, a company has a marketable product and can raise money by selling this package to an issuer. The issuer converts this into a tradable security.

- The sale to an issuer separates the lease pool from the originator's balance sheet. This allows issuers to raise capital to finance the purchase of assets more cheaply than possible based on the originators' balance sheet strength.

- Securitization is better than conventional debt because it doesn't inflate a company's liabilities. Rather, it generates funds for future investment without burdening the balance sheet.

- The flexibility of securitization transactions allows issuers to customize the risk-return profiles of loans into tranches, better catering to an investor's risk tolerance.

- It is effective in mature and emerging markets, as banks and entities have turned future cash flow into liquified capital.

- It transfers risk away from an entity that doesn't want to bear it.

Cons of Securitizing

The financial crash of 2008 highlighted the many flaws and negative aspects of conducting Debt Securitization.

As the process grew to be more and more complex, and as more asset types were used in the process, the downsides of this investment vehicle were also exposed. However, the lack of regulation and the sensitivity of key variables highlighted the cons.

Below are some flaws of Debt Securitization:

- It may reduce the quality of the asset portfolio. For example, if you securitize an A-grade/Senior tranche, you are left with an overall more risky portfolio.

- It is expensive due to management and operational costs, with many fees associated with the process(legal, underwriting, administrative, and rating).

- They often require large-scale structuring and aren't cost-efficient for small to mid-size transactions.

- Being a structured transaction, it may include inherently risky structures such as prepayment penalties, credit loss, and other stipulations.

- Changes in interest rates impact some assets more severely than others, which may impact the securitization depending on the assets within the pool.

Regulation within the Industry

In the years leading up to the 2008 crisis, the regulations and standards used to underwrite residential mortgages and other loans had rapidly degraded.

With a lender's ability to originate and offload the associated credit risk, the ideology around the industry became volume over quality.

The lender could pocket their origination fee and then unload the risk to someone else. This ultimately led to increased moral hazards via over-reliance on credit ratings and conflicts of interest. In addition, risks were hard to assess due to these loans' repackaging and distribution of ownership.

After the financial crash of 2008, which disrupted the global economy, arguably the greatest takeaway from this event was the need for stricter regulations and laws governing how the debt securitization process operates.

Since 2008, the focus has been on creating a safer and more stable industry so another major financial disaster never happens again.

Key issues that have emerged from the industry:

- Due diligence is needed on the originators of the assets, the assets themselves, and origination practices.

- The enforcement of remedies, how remedies are meant to work, and the uneven application of remedies.

- The untransparent nature of many transactions and how risk within these transactions is distributed.

Examples of Regulatory Responses:

- Proposed and implemented legislation in the US, UK, and Europe.

- US - Proposal of credit risk retention by sponsors of ABS

- Self-policing by market participants via global policy changes within banks requires different approval processes for transactions and more stringent due diligence mandates.

- Increased scrutiny of deals brought to the market. Government's Role on Securitized Debt Instruments

Government's Role on Securitized Debt Instruments

The financial crisis of 2008 highlighted the importance of establishing more expansive and strict regulations for developing these markets.

In 2009, the Emerging Markets Committee (EMC) of the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) established a Task Force on the Current Financial Crisis.

They had two mandates:

- Assess and identify the impact of the current financial turmoil on emerging markets, regulatory issues, and the responses.

- Review the role of structured financial products (SFP) in developing emerging markets, focusing on developing principles or best practices for securitization in emerging markets.

They created a report that encouraged authorities to ensure enabling conditions are in place for securitization in emerging markets:

- A stable macroeconomic environment

- Clear and robust legal framework

- Robust accounting principles

- A neutral tax system

- Investor education

The report also had key recommendations for emerging markets, encouraging regulators to:

- Collect a minimum set of data on securitized markets.

- Enhance disclosure for both public and wholesale markets.

- Foster trading through public venues.

- Foster the development of pricing vendors, which should be regulated.

- Develop a basic framework for key market participants.

- Enhance business conduct obligations.

- Align credit rating agencies' regulations with the IOSCO Code of Conduct Fundamentals for Credit Rating Agencies.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?