Swap Contracts

Allows two companies or investors to swap cash flows or liabilities of each transactor’s underlying asset

What are Swap Contracts?

A swap contract allows two companies or investors to swap cash flows or liabilities of each transactor’s underlying asset. In simpler terms, the agreement will enable parties to switch out items that may be a risk to the company for something of less risk.

Famous examples of swap contracts include:

- Interest rate swaps (floating interest for a fixed rate)

- Currency swaps (foreign currency to domestic)

- Total return swaps (asset for a fixed rate of interest)

Many variations are used for specific reasons to hedge against risk or gain a capital advantage over competitors.

Each underlying asset from the transactors is titled as a 'leg' of the swap. It is most common to see exchanges used upon company cash flows.

The notional principal amount describes the asset's theoretical worth. The term is used as the cash flows/assets never actually change hands when the contract is put in place; however, in an academic sense, they do.

For instance, only the rates change hands through an interest rate swap contract. The loan in which these rates are attached is the notional amount. The same goes for the case of a bond, where the face value of the bond would be the notional amount.

Imagine two companies being the transactors in a quick example of how a swap would work. Each has loans for the same monetary amount, tied to different interest rates. Company X has a floating interest rate, whereas Company Y has a fixed rate.

An example is an interest rate swap, which works when both sides have opposite views on future rates. Let's say Company Y feels that interest rates are about to come down and, therefore, wants to switch its fixed rate to a floating rate.

On the other hand, Company X has the opposite opinion. Company X feels future interest rates are bound to go up. Therefore, the company searches for a fixed rate to lock in its current low rate. With both sides having opposite views, these companies are fit for an interest rate swap.

By developing a contract, companies can switch out their rates with one another.

At the end of the contract, whoever was correct in predicting the future rates will have profited from using the swaps contract.

Key Takeaways

- A swap contract is a derivative allowing the exchange of cash flows from each party's underlying asset. Depending on the swap, cashflows may be based on an interest rate, index, commodity, or currency exchange rate.

- Interest rate swap contacts are the most popular; typically, the swap is exchanging fixed and variable interest rates.

- Swap contracts are custom tailored to every situation and are traded privately over the counter (OTC).

- Swaps and companies using swap contracts can be risky. Filing regulations are not ironclad. Therefore, companies can leverage up while leaving no paper trail. Scenarios similar have led to significant financial crashes, such as the 2008 financial crisis.

Swaps Market

The swaps market is different from where most derivatives get traded. Unlike options and futures, swaps aren't exchange-traded instruments; they are customizable contracts privately traded over the counter (OTC).

Being traded over the counter raises concerns about exposed risk. OTC markets are riskier because companies and individuals are not always obliged to post all company financials.

The lack of company filings makes it difficult to evaluate a company's transactions and determine its credibility. Therefore, companies must take extra caution when dealing with OTC contracts, as the other party is always at risk of defaulting on their side of the contract.

Companies have exploited that secrecy to their advantage to hide their fillings from other companies and creditors. However, situations can become quite serious when a company is far over-leveraged but keeps it under wraps.

A company that would be far too risky to deal with seems perfectly stable from the surface until one party finds out and the house of cards falls. Famous economic blowups, such as the 2007-08 crisis and the fall of Archegos, were caused by similar actions.

Most of the swaps market consists of companies and firms. However, individuals are allowed to partake as well. As a result, there are many variations of contracts that are used for different situations, each traded over the counter.

Interest Rate Swap

As mentioned above, the interest rate swap is the most common form of the swap contract. It usually involves two agents switching fixed and variable/floating rates.

A company may want to swap the interest rates on a principal amount if they are speculating that rates may suddenly change.

Once again, the swap only works if both sides have separate views on the future and each party's notional amounts are equal and in the same currency.

One side may believe rates are going down, so they'll switch to a variable rate, swapping their fixed rate with the other company that considers rates will go up.

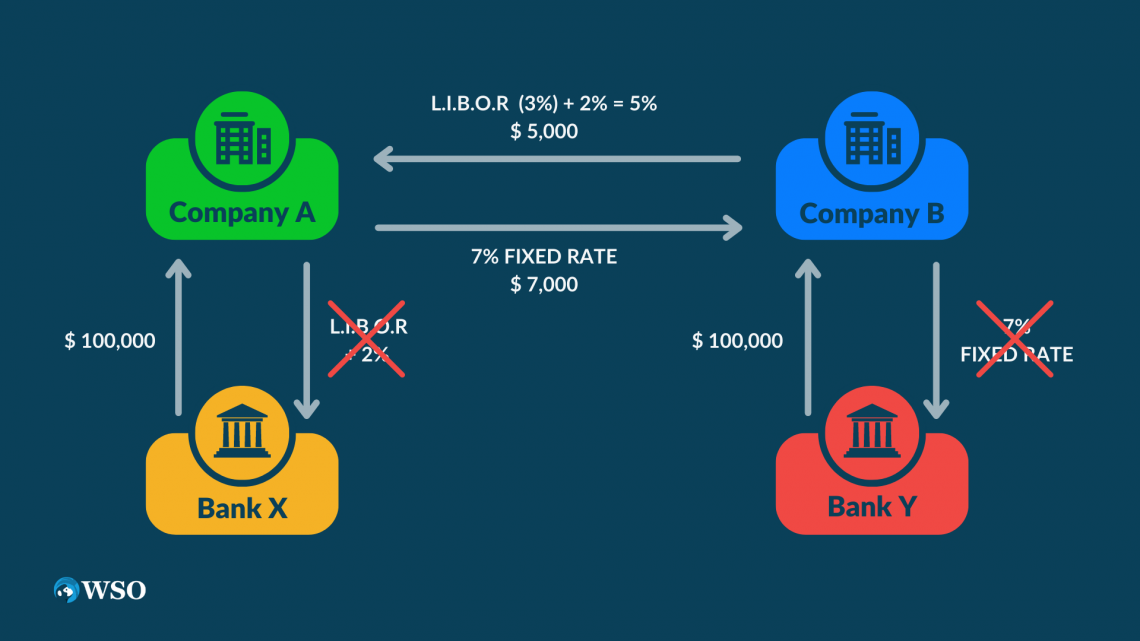

How the interest rate swap works: Company A, which currently has a variable rate, will take over Company B's fixed rate. At the same time, Company B will pay Company A's variable rate until the end of the contract.

The contract payment date will end on the settlement date, while dates throughout the contract are settlement periods. Swap contracts are customizable. Therefore, interest may be paid on the settlement periods monthly, quarterly, yearly, or at any decided time interval.

At the end of the period, the net amount is generally calculated, and the party that profited is paid.

Complete Interest Rate Swap Example

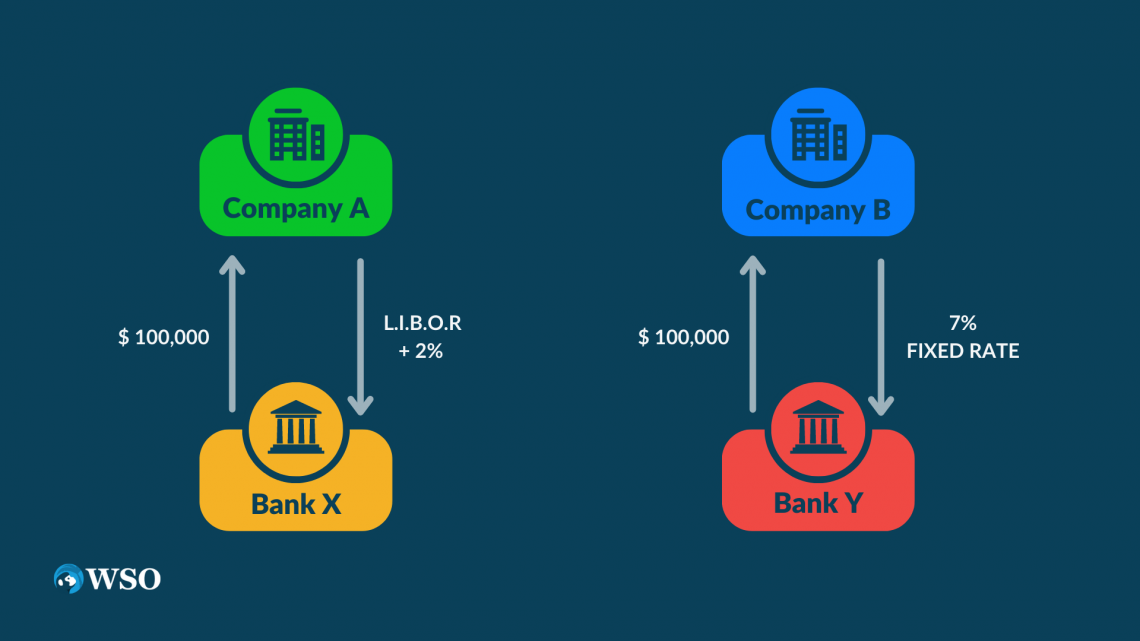

Let's say Company A has borrowed $100,000 in 10-year bonds at a variable interest rate. The London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) can determine all variable rates. LIBOR sets the benchmark variable interest rate at which global banks lend to one another.

The swaps market has referred chiefly to LIBOR as a benchmark until 2020. Others have come into play today, such as SOFR (secured overnight financing rate). However, we will continue with this example using LIBOR.

On top of LIBOR (which, for example, is set at 3%), Company A offered to pay 2% interest (i.e., currently 5% total) on their initial loan. Now, the company speculates that interest rates will continue to rise and desires to get out of its variable rate.

Company A will now find another company willing to pay its variable rate in exchange for a reasonable fixed rate. First, they will search until another transactor pays the rate of LIBOR plus 2%, which, to their luck, Company B is willing to do. Now, the two will swap rates.

Company B accepted the trade because they feel strongly that rates are on their way down and want to capitalize on the lower payments. Therefore, Company B will take their 7% fixed rate off their notional loan amount and swap it for Company A’s variable rate.

At this point, the contract looks as such:

Company A benefits if interest rates rise past 7%, which is the fixed rate.

Company B profits if LIBOR stays below 5%, as 5% + 2 % = 7%, which was the old fixed rate they swapped out. If interest rates come down to 3%, the company now only pays 5%, which beats the previous 7%.

These swaps and almost every other kind of swap can also be entered into by speculators who don't have any relation to the underlying asset. In this case, they would have no loan and merely want to gain profits from a possible movement in LIBOR.

Types of Swap Contracts

There are other types of swap contracts, including commodity, currency, debt-equity, and total return swaps, all of which do not include swapping different financial instruments.

1. Commodity Swaps

A commodity swap is the exchange of a raw good's fixed price for a future variable fee. Commodity swaps benefit companies and investors who buy/sell essential goods to produce and manufacture final goods and services.

As commodities are exposed to price changes, sudden increases in the price of raw goods that affect the company's supply will hurt profits. A commodity swap allows the company to lock in a fixed price for its supply.

For example, two transactors participate in a commodity swap of 10,000 barrels of crude oil. One party (transactor A) currently pays the floating price of their raw goods, but with worries about price increases, they want to swap for a fixed price.

The exchange of such rates will be complete once they find a company (transactor B) willing to accept their current floating rate and, in return, offer their fixed rate.

If the price per barrel of crude oil rises in the future, transactor A will benefit, as transactor B is left paying more significantly than the current floating price.

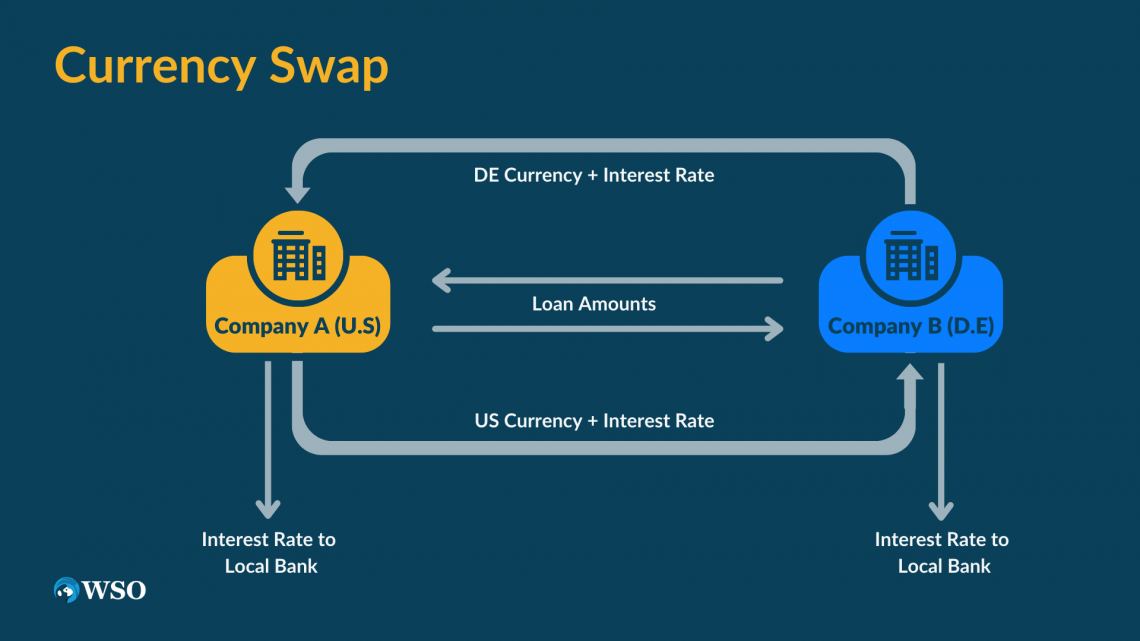

2. Currency Swaps

They allow both parties to swap the interest rate on the loan of the currency of their cash flows. They are helpful to companies operating in foreign countries who are facing difficulties as foreign banks don't prefer lending to international companies.

As a result of the unwillingness of the foreign banks to extend the loan, they will offer higher interest rates compared to what the company would receive in their home country.

For a scenario, the company may find another company within the foreign country facing the same issue in their home country. Then, using each company's home banks, they may swap the rates they may each take out loans at and change the interest rates on the currency.

Unlike an interest rate swap, currency swaps involve both parties exchanging the notional amount and the interest rate.

For example, if a US company was operating in Germany. As the US company is new to the country, they are offered a 10% interest rate from the local banks. On the other hand, a German company operating in the US is also having difficulties. Therefore, both companies are fit for a currency swap.

Each company may go to its trusted domestic bank and get the agreed-upon loan amount, with the favored interest rate attached. Then, the companies may swap different currencies along with the rates and pay off each other's loans.

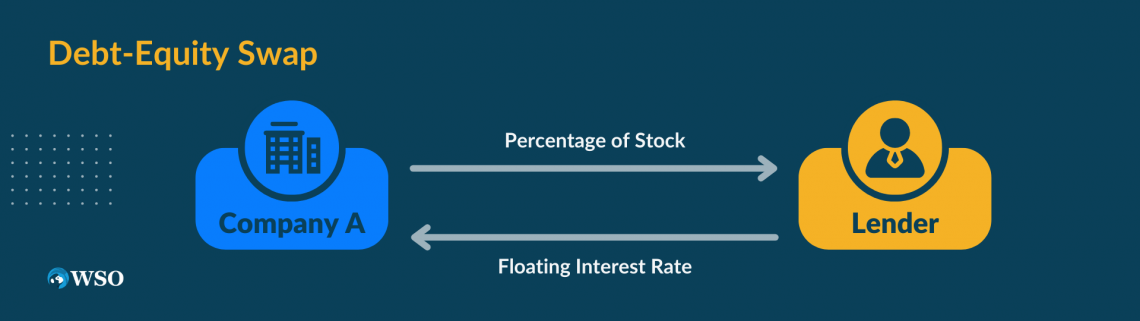

3. Debt-Equity Swap

A debt-equity swap allows transactors to swap obligations/debt for an asset of value. The contract is often used as a refinancing tool where the debt holder will exchange an equity position in return for the write-off of their debt.

Debt-equity swaps are used by struggling companies looking to offload their debt to stay afloat. For a company's sake, the trade would consist of bonds for stocks.

In an example where a company was struggling to pay off debts, they would have few choices but to make a debt-equity swap. The company and lender would work out a percentage of company shares that fits the price of the debt offloaded from the company.

For struggling businesses to persuade lenders into debt/equity swaps, they may offer a favorable trade. For example, a company in such trouble may offer a 1:1.5 swap ratio, meaning the lender receives 1.5x the loan's value in company stock.

That way, a company may persuade the lender to accept stock of what looks like a dying company.

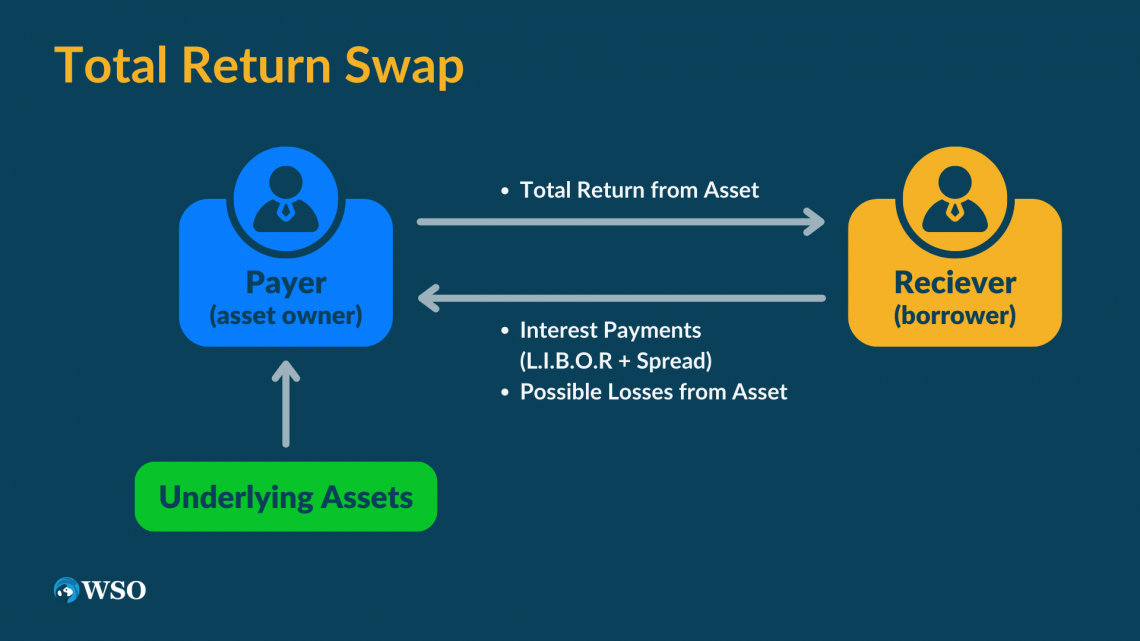

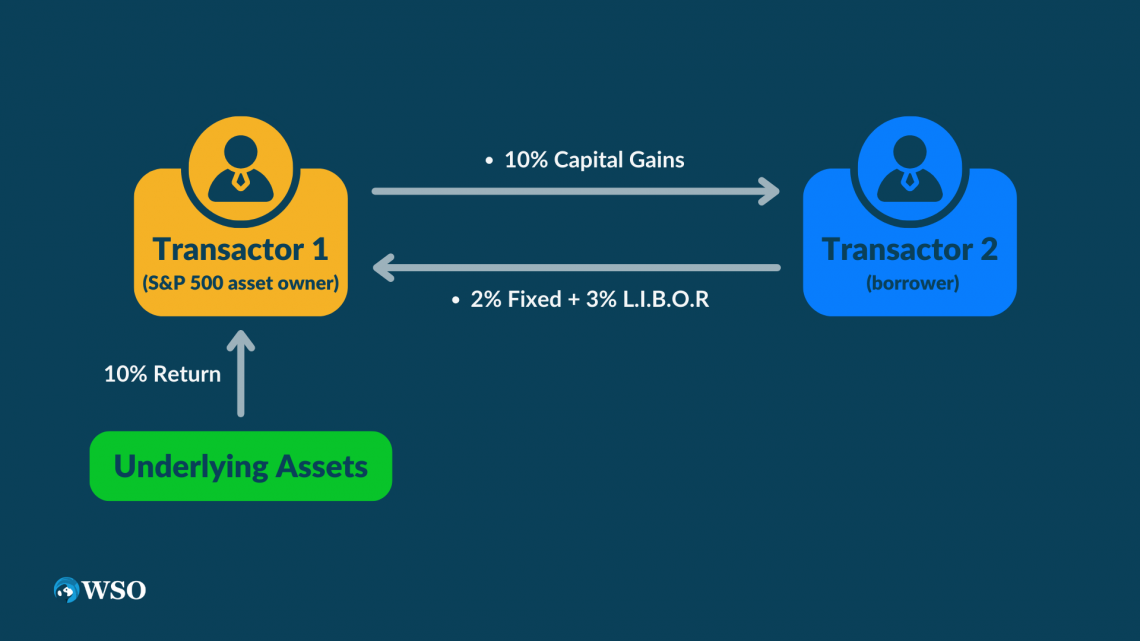

Within a total return swap (TRS), the return of an asset, such as a stock, is exchanged with another party for a set interest rate.

The swap consists of one party making interest payments (fixed or variable) while the other party pays back the capital gains from the asset.

A company may use a TRS if they desire to reap the gains of, say, company stock without actually having to hold the position.

For example, two agents enter a total return contract for one year on a $100,000 notional principal amount. The first company, Company A, has a hunch that the S&P 500 index is likely to increase.

However, Company A doesn't care to own the stock. Using a total return swap contract, the company can find another party, Company B, who owns a position with a size of at least the notional amount and wants to enter a contract.

Company B would enter as they believe the S&P 500 will decrease and would like to exchange the index's capital gains for a positive insured interest rate from company A.

Therefore, Company A offers Company B a 2% interest on top of LIBOR in return for whatever the S&P index returns.

For company A to win from the swap, the S&P 500 must return more than 2%+LIBOR because they must pay Company B either way. For instance, if the S&P sees a 10% return and LIBOR is at 3%, Company B will pay Company A ($100,000(10%-5%)), which is a P/L+$5000 for Company A.

On the other hand, if the index does not do so well and falls 10%, Company A must pay Company B the net losses and their previously agreed payment. This would total 10%+5%, therefore, ($100,000(15%)) giving Company B a $15,000 profit.

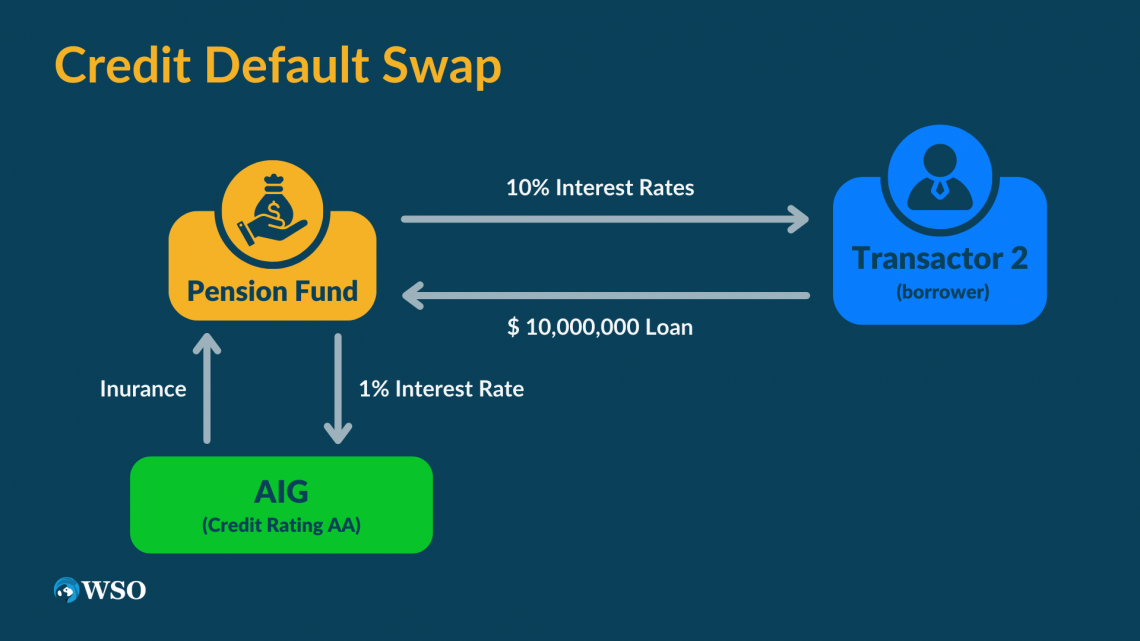

A credit default swap or CDS is a form of financial derivative allowing one party to take on the credit risk of others.

A credit default swap protects the buyer, who has loaned funds to another party. Since the buyer needs a CDS, the debtor probably has a lower credit rating.

Therefore, the buyer will use the swap to bring in another transaction, say an insurance firm, to offer protection in case the party defaults.

Imagine a pension firm with $10 million to invest, and Company A, a small firm with little reputation, has offered them a 10% interest in return for the sizable loan.

Company A has a mediocre credit rating. Therefore, a firm like a pension plan could never do that deal, as they only loan to highly trusted companies.

A CDS comes into play when an insurance company, such as AIG, steps into the deal and says to the pension firm that they will take on the debt if Company A defaults. In return for being a fallback, the insurance company requests an interest fee of 1%.

The pension plan doesn't need to care about the credit rating of the small firm because they now have a highly creditable firm backing them up if they default. So the pension firm agrees as they will benefit 9% (10%-1%) with no excess risk.

Why Are Swap contracts Used?

There are two main reasons a company or individual would use a swap contract: hedging risk and gaining a competitive advantage. Within the daily operations of a business, they endure all sorts of interest rates and currencies, which expose risks that swap contracts can relieve.

1. Risk

If a company receives a fixed rate of interest on their loans but a floating rate on their deposits, this discrepancy opens the company to many troubles.

To resolve this, they will undergo a fixed-floating interest rate swap to convert their fixed rate to a floating one, assuming they believe rates will change for the better (decrease). Now, their floating rate on loans matches the floating rate on deposits.

2. Competitive Advantage

A company may use a swap contract to gain a competitive advantage. Imagine a company operating in the USA that wants to expand into the UK. Being a small company trying to expand to a new country may be difficult.

The US is likely to offer more favorable loans to the company, as they are more known there. The company could take the more advantageous option and use a currency swap with another business with the same issues coming from the UK.

Exiting a Swap contract

If a transactor must opt out of a swaps contract before the expiration date, there are four ways to do as such.

1. Buy the counterparty out. Similar to options and future contracts, the value of a swap contract can be calculated. If one transactor wishes to terminate the agreement early, they may pay the other party the market value.

However, this is not always the case. For example, to exit a swap through a buyout, there must have previously been set terms allowing a possible buyout or the counterparty's consent beforehand.

2. Enter an offsetting swap: Another way a party can exit a swap is by offsetting their current exchange. They get a second swap, opposite their first contract, that will cancel out the original trade.

3. Sell the swap to someone else: Using the calculable value of the swap, a transactor looking to exit their position may sell the trade to another party. Selling an exchange also requires the consent of the counterparty.

4. Using a swaption: A swaption or swap option allows the purchaser to set up, but not enter, an offsetting swap once the original exchange is executed. Swaptions are similar to offsetting trades. However, they carry less risk.

Researched and authored by Thomas Fallow | LinkedIn

Free Resources

To continue learning and advancing your career, check out these additional helpful WSO resources:

or Want to Sign up with your social account?