Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)

Primary valuation methods used by finance professionals to derive a company's fair value.

A discounted cash flow model is one of the primary valuation methods used by finance professionals to derive a company's fair value. Therefore the price investors should pay for them.

Valuing a company is critical to most front-office roles, including those working in investment banking, private equity, or asset management.

It is common to find analysts and associates being the ones valuing a company and creating DCFs. It is essential to ensure that the analysis is done accurately because it affects current transactions and offer prices.

Executing a discounted cash flow model meticulously is a highly sought-after skill that Morgan Stanley even recommends investors approach capital markets as if "everything is a DCF model."

Suppose you work in the Goldman Sachs mergers and acquisitions division and are trying to help Microsoft acquire Activision Blizzard in one of the world's most significant acquisitions of the decade. How much should Microsoft pay to reach the target, and why did they pay $69 billion?

What if you are an asset manager trying to decide which stock to invest in? At what price is the stock underpriced?

The DCF model was designed to answer these questions. It is one of the three most common valuation methods investment bankers use. The other two most prominent valuation methods are:

- Comparable company analysis

- Precedent transactions analysis

If you are interested in working for JP Morgan or Goldman Sach's front office divisions, it would be ideal for you to know what DCFs are, why they are used, their assumptions, and how it differs from other financial modeling techniques.

What does a DCF model tell us?

As with a comparable company or precedent transactions analysis, any valuation method generally aims to tell us the same thing: how much a company is worth.

However, a DCF model takes a fundamental valuation approach instead of a relative valuation approach by deriving a company's intrinsic value.

This is done by generally projecting a company's future free cash flows and discounting all of it into present value to determine how much cash is available to the relevant stakeholders if they decide to buy a share of the company.

Here are the simplified steps for executing a DCF:

-

Project the company's future free cash flow for the next 5 to 10 years

-

Calculate the company's terminal value (assuming that the company will operate after the projection period)

-

Discount the company's future free cash flow & terminal value using the company's cost of capital

-

Add the company's non-operating assets to the present value of all future free cash flow & terminal values

-

Subtract debt & non-equity claims to arrive at the company's estimated market capitalization

-

Divide by the number of outstanding shares to arrive at a share price

While this may seem pretty straightforward, there is much to understand here. So let's go deeper into what each step means.

Projecting future free cash flows

There are two types of future free cash flows to project: levered free cash flow (FCF) or unlevered free cash flow (UFCF). The more common projection is unlevered free cash flow.

What is the difference? Unlevered free cash flow outlines the cash flow available to debtors and shareholders, while levered free cash flow outlines the cash flow available to shareholders.

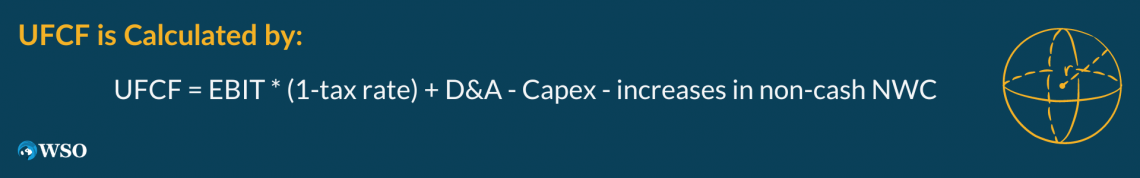

Once you understand the difference between both, it doesn't matter which one you want to calculate. You can derive a company's unlevered free cash flow from its three financial statements (income statement, balance sheet, & cash flow statement). The formula is:

UFCF = EBIT * (1-tax rate) + D&A - Capex - increases in non-cash NWC

Where:

- EBIT = earnings before interest & taxes

- D&A = depreciation & amortization

- Capex = capital expenditures

- NWC = net working capital

- Tax rate = corporate tax rate for target company

The idea of the UFCF is to determine how much money is available to creditors and shareholders. Therefore, you would:

-

Take the EBIT and multiply it by (1- tax rate) to adjust for the effect of taxes on the debt & shareholders' earnings.

-

Subtract capital expenditures because that is the capital the firm has already expensed out on operations.

-

Add back D&A because it is a non-cash expense. It was merely an accounting technique designed to spread out the cost of the company's assets (there was no actual outflow of cash from D&A in an income statement).

-

Subtract any increase in noncash net working capital because it represents an increase in money invested and therefore not available to debt & shareholders.

To find the levered free cash flow, subtract UFCF from the company's debt obligations (interest expenses or principal payments).

You can be very creative when forecasting a company's UFCF. The first step would generally be to look at how the historical components of the company's UFCF changed over time.

Perhaps you see that the company's EBIT has been steadily growing at 5% annually for the last 20 years. Because of this, it might be fair to assume that it will continue to grow at 5%.

However, the industry it operates in is about to boom, and because of that, you should estimate that its EBIT will grow at a rate higher than 5%.

You can be as creative as you want; however, it might be better to be conservative and assume adverse outcomes rather than positive ones.

Calculating terminal value

It is unrealistic to keep projecting a company's future free cash flow after a long enough period.

Therefore, it would be fair to assume that the company will grow at a constant rate using high-level assumptions, and the sum of all its future cash flow after the projection period is known as the terminal value.

The terminal value can be calculated using two options:

- Growth in perpetuity method

- Exit multiple methods

Growth in perpetuity method

At this point, you will calculate that the firm's UFCF will grow consistently, g. Then using the formula below, you'd be able to find the terminal value (TV) of the company:

TVs = UFCF(t + 1) / (r – g)

or

TVs = UFCFt * (1 + g) / (r – g)

where:

- g = terminal growth rate

- r = discount rate

Most analysts will use a lower terminal growth rate because it is unlikely that a company will grow at a high growth rate forever.

It is also common for analysts to set a growth rate similar to the country in which the company operates GDP growth rate.

There is some belief in the convergence between the country's and the company's growth. So if the GDP of Britain increases YoY by 3.2%, analysts would utilize a TV value of 3.2% for their calculations.

The discount rate you would use in this scenario is the company's weighted average capital cost (more below).

However, if you were projecting the company's levered free cash flow within this projection, you would only discount the company's cash flows using the cost of equity.

This equals out because UFCF represents the money available to both debt & equity holders while LFCF represents the money available to only equity holders.

Exit multiple methods

Using the growth in perpetuity approach may be challenging to estimate the company's long-term growth rate. Therefore, a shortcut may be to decide a price the company should trade based on its earnings.

For example, you expect company X to have an EBITDA of $400 million by the end of the year, and you expect the company to trade at an EV/EBITDA value of 10x.

With this assumption, we can calculate that Company X's enterprise value should be worth $4,000 million.

How would you decide on what EV/EBITDA value to use? The best way is to look at the type of company you are analyzing and find comparable companies or use its industry average EV/EBITDA value.

Growth in perpetuity vs. exit multiple

There is no "superior" method to calculate a company's terminal value. The truth is that both ways have their strengths and weaknesses.

The consensus is that the multiple exit methods infuse reality into the analysis because the multiple used were obtained from market prices and their underlying sentiments.

However, if you've looked at a price chart, you can see that any company's price fluctuates daily. That would result in a daily fluctuation in a company's EV/EBITDA, and it may be challenging to decide precisely what number to use.

Whether you use the growth in perpetuity or exit multiple methods, there will be a conceptual contradiction. While DCFs are designed to project future cash flows, you will likely base your assumptions on historical figures.

To learn more about how to calculate a terminal value, click here.

Discounting UFCF & terminal value

Once you have projected the company's UFCF and terminal value, you must discount those cash flows into present value. The concept of discounting is straightforward, and the formula is shown below:

Future value = present value * (1 + r)t

Present value = future value * 1/(1+r)t

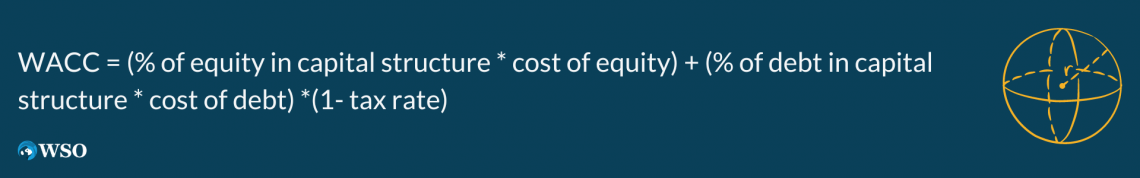

When discounting the company's UFCF, you can determine its cost of capital by using the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) formula. The formula is shown below:

WACC = (% of equity in capital structure * cost of equity) + (% of debt in capital structure * cost of debt) *(1- tax rate)

The WACC formula aims to determine a company's blended cost of capital across all sources to finance its assets. It also can determine the rate at which the company's future UFCF is discounted.

WACC more accurately captures the company's cost of capital because WACC incorporates the fact that most firms are financed by both equity and debt.

It wouldn't be fair to discount the company's cash flow using ONLY the cost of equity or debt because they have different rates of return, and the WACC formula can capture that when calculating the cost of capital.

However, take caution because you would use the cost of equity to discount the company's future cash flows if the discounted cash flow model is projecting LFCF because the LFCF has already controlled for debt repayments and outlines the cash available to ONLY equity holders.

It adds up all the discounted UFCF of the company, resulting in its enterprise value. A company's enterprise value essentially shows the total value of the company's debt and equity, similar to a balance sheet.

The last step would be to add and subtract certain items to derive the equity value. Equity value is a company's total value attributed to the shareholders.

There is more to understand regarding how the WACC formula accurately captures a company's cost of capital. To learn more about the logic behind the WACC formula, click here.

Final adjustments

The final step is to adjust for other items. The steps outlined so far essentially outline the money available to both debt and shareholders. The next step will determine how much of that money belongs to shareholders (therefore, how much they should pay for the target).

Subtracting debt & equivalences

Money used to pay off interest expenses and principal payments does not go to shareholders. Therefore, you should subtract debt repayments.

As an ordinary shareholder, you would also have to subtract the value of any preferred shares or minority interests because that money would not go to you.

Adding nonoperating assets

Companies will likely have assets that do not contribute to their revenue. For example, if you would pay $100 to own a lemonade stand, you should be willing to pay $200 for that same lemonade stand with $100 in cash or cash equivalents.

The discounted UFCF did not account for these nonoperating assets, and this is where you have to add them back.

After completing every step, you have the company's estimated market capitalization. This calculates how much you should pay to acquire the company, but if you'd like to know the share price, you would divide the market capitalization by the total outstanding shares.

Shares outstanding can be found in many places, including being listed as capital stock on their balance sheet or in their 10-K and 10-Q filings with the Securities Exchange Commission.

Discussions of the discounted cash flow

Theoretically speaking, the discounted cash flow model is very sound. However, many will argue that the DCF projection is likely inaccurate and far from reality.

The biggest reason is that this model is highly assumption-heavy. To execute this model, you'd have to make assumptions about:

- Future free cash flows

- Terminal Value

- Growth rate

Economic situations are unpredictable—the further the time horizon, the murkier the prediction. So while analysts are expected to value companies with DCFs, they will probably carry out other valuation techniques, which would not be perfect.

All in all, these financial modeling techniques are used as benchmarks and guidelines instead of the absolute value of a company.

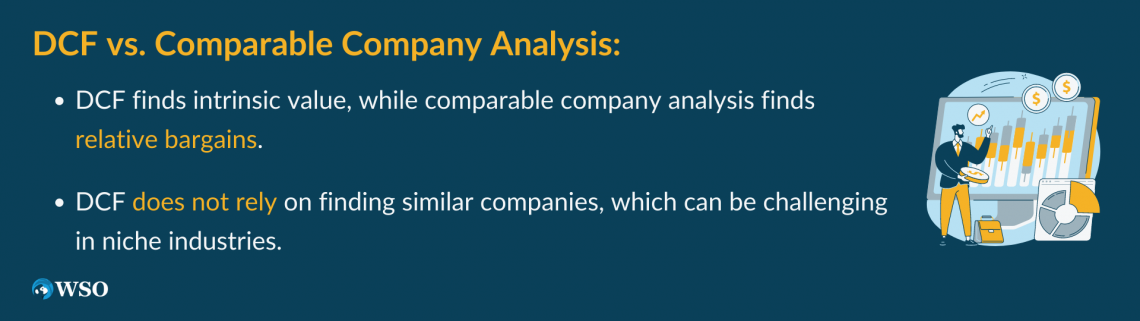

Discounted cash flow vs. comparable company

Analysts who use the comparable company analysis to value a company will find publicly traded companies and their existing price-to-earnings (or any other relevant multiple) ratios and compare them to the target.

Therefore, the DCF and comparable company analysis are very different valuation methods.

While the DCF takes a fundamental approach by finding an intrinsic value of the company, the comparable company analysis takes a technical approach by finding a relative bargain.

One benefit of the DCF over the comparable company analysis is that it does not rely on finding a similar company to conduct the research.

You'd be surprised how difficult it would be to find a comparison with similar assets or revenue streams when the target industry is very niche.

To learn more about the comparable company analysis, click here.

Discounted cash flow vs. precedent transactions

The precedent transactions analysis is considered a subset of the comparables company analysis. Precedent transactions are done by looking at the prices paid by investors to acquire similar companies.

This is different from looking at the market price because it focuses on specific transactions and their specifics, including the type of company, its size, and the type of buyer.

While a DCF can be calculated on every transaction, precedent transactions are much more relevant to analysts working on an M&A deal.

The approach in a precedent transaction is also more technical than fundamental, where you'd be trying to look at similar transactions and relate their value to the target.

To learn more about precedent transactions, click here.

How To Answer The "Walk Me Through A DCF" Question?

In an interview, it is essential to keep your technical overview high. Therefore, start with a high-level overview and be ready to provide more detail upon request.

-

Project out cash flows for 5 - 10 years depending on the stability of the company

-

Discount these cash flows to account for the time value of money

-

Determine the terminal value of the company - assuming that the company does not stop operating after the projection window

-

Discount the terminal value to account for the time value of money

-

Sum the discounted values to find an enterprise value

-

Subtract Net Debt and divide by diluted shares outstanding to find an intrinsic share price.

Researched and authored by Jasper Lim | LinkedIn

Free Resources

To continue learning and advancing your career, check out these additional helpful WSO resources:

or Want to Sign up with your social account?