Pareto Efficiency

Also known as Pareto Optimization, this concept refers to a situation in which one person cannot be improved without making another worse off.

What Is Pareto Efficiency?

Pareto efficiency, also known as Pareto optimization, is a concept that refers to a situation where one person cannot be made better without making another worse off.

Pareto optimization checks if one variable can be improved without harming the performance of another in these fields. In other words, it is a situation in which no Pareto improvement can take place.

This is an economic concept that aims for a society in which each individual and organization is at its optimum. This means each person is at the best point they can be, given other members of the society.

The term was coined by Italian economist and civil engineer Vilfredo Pareto. He used the concept in his works on income distribution and economic efficiency.

This concept can be applied to production and x-inefficiency in economics. It is an incredibly vital tool in studying Welfare Economics and Neoclassical Economics.

In a world under perfect competition that allocates its resources such that they are utilized to their total capacity, every economic agent would be at their highest achievable standard of living, i.e., Pareto Efficient.

Apart from economics, Pareto efficiency is also used in biology and engineering to assess the performance of each available option.

Key Takeaways

- Pareto efficiency, or Pareto optimization, describes a scenario in which one person cannot be made better without making another worse off.

- Vilfredo Pareto coined the term. This concept aims for an optimal society in which each individual and organization reaches their highest potential given the constraints of society.

- Equity considerations may conflict with Pareto efficiency, highlighting the need to balance efficiency with fairness.

- Pareto efficiency overlooks real-life distributional challenges, externalities, and the achievability of optimal outcomes.

Understanding Pareto Efficiency

In a state of Pareto efficiency, no change could result in one person making more than the other. This may mean that any change would result in at least one of the individuals being worse off.

The concept is commonly used in the field of resource allocation and production, which is measured along the production possibility frontier (PPF).

The production possibility frontier (PPF) is the graphical representation that displays all the possible options for producing two products using different production factors, ensuring that all the resources are utilized effectively and efficiently.

Pareto optimization does not account for the consequences of the degree of inequality of distribution since Pareto optimization is not the same as societal optimization.

Considering that the concept isn't the same as societal optimization, Pareto efficiency doesn't require the total equal distribution of wealth where a few wealthy individuals hold the majority of the resources; an economy can still be Pareto efficient.

One of the main critiques of Pareto efficiency is that the concept acts as an ideological tool that neglects or discounts embedded structural societal challenges.

Example of Pareto Efficiency

To better understand the concept of Pareto efficiency, let us consider the following example of a used bicycle.

Suppose Tamer wants to sell his bicycle for $40. On the other hand, Zakir wants to buy a bike and is willing to pay up to $60 for it. If both Tamer and Zakir agree on the $50 transaction, the transaction can be said to be Pareto efficient.

This is because both the buyer (Zakir) and the seller (Tamer) are better off by the same amount, i.e., $10, after the transaction.

Any price between $40 and $60 would be Pareto Efficient since Tamer is getting more for the bicycle than his valuation, and Zakir is getting the bike for a cheaper rate than what he was willing to pay.

Let us now consider another example of this concept in action.

Suppose Kate has a cake. She can distribute it among Ally, Mike, and Sadie.

In this case, regardless of her choice of distribution, the outcome is Pareto efficient for Ally, Mike, and Sadie because they are all better off, and neither is put in a worse situation.

Giving all three an equal share of the cake is just as Pareto efficient as providing half of the cake to Ally and half to Mike.

Pareto optimization can also be applied to the context of production. The following section introduces the production possibility frontier and potential for optimal efficiency within an economy.

Pareto Efficiency and Production Possibility Frontier

The Production Possibility Frontier (PPF) is a locus of all points depicting the total amount of two goods that can be produced, given that all economic resources are employed for their production.

The PE concept can also be used to measure the efficiency of a particular allocation of two goods on the PPF.

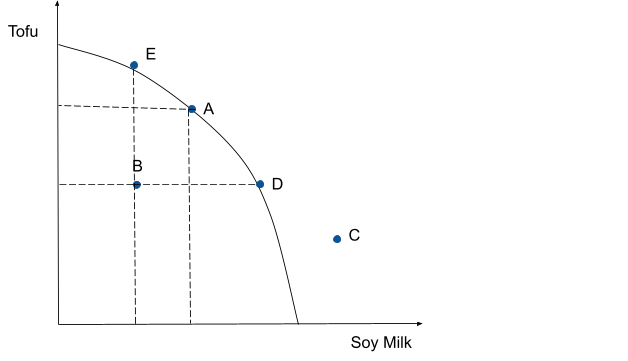

Consider the diagram below, depicting a PPF for an economy that produces only tofu and soy milk.

Here, at point A, the economy is operating on the PPF. Therefore, at this point, it is not possible to produce more tofu without preceding some amount of soy milk.

Similarly, the economy cannot produce more soy milk without forgoing some amount of tofu.

Hence, point A is Pareto efficient.

On the other hand, point B lies within the PPF. At this point, the economy is not utilizing all of its resources. More tofu can be produced (up until point D) at the same level as soy milk.

Similarly, more soy milk can be produced (up until point E) at the same level as tofu.

Hence, point B is Pareto inefficient [discussed in the next section].

Finally, point C on the graph lies beyond the PPF. This means the economy does not have enough resources to produce at that level. Hence, point C is simply unattainable.

Pareto Efficiency and Market Failure

Market failure is when resources are inefficiently distributed in a free market.

As discussed in the previous section, Point B lies within the PPF. When the economy produces at this point, it is not optimizing all its resources. The economy could have more by employing more resources.

The economy still has the potential to improve, but resources are allocated inefficiently. This represents a failure in the market.

Consider, for example, the overconsumption of demerit goods like cigarettes or alcohol. By consuming these goods, consumers face costs in the form of unproductivity, greater exposure to fatal diseases, and a shortened life span.

Additionally, in the case of smoking, non-consumers are also left exposed to these negative externalities in the form of pollution and passive smoking.

There is room for improvement. For example, the government can levy a tax on the consumption of demerit goods.

This tax would raise the cost of consumption, encouraging individuals to quit smoking or drinking. Not only would this benefit the consumer, but it would also benefit non-consumers affected by the externalities of consumption.

The economy will then be able to improve productivity and revenue generated from taxes on, say, cigarettes, which could be used to treat medical issues resulting from smoking.

The possibility of this Pareto improvement implies that the market is not functioning to the best of its ability. It is not Pareto efficient, and there is a failure in the market.

Types of Pareto Efficiency

So far, we have discussed PE, assuming it is vital. However, this concept has different aspects that are important to consider. The following section goes over some of these.

Weak PE

Under weak PE, all agents are not strictly better off. For example, assume an economy with two resources - X and Y.

Leo values these resources at (5, 5). Katrina loves the resources at (10, 0).

If the utility profile is (10, 0),

- It is weakly Pareto efficient since no other allocation is enormously better for both agents.

- Leo is strictly better off for a utility profile of (10, 5) since he prefers an allocation with resource Y. Still, Katrina is only weakly better off as she is already receiving her optimal level of resources X and Y.

- Since Katrina's preferred resources did not increase, the outcome is weakly Pareto efficient for her.

Constrained PE

As the name suggests, this type of efficiency occurs when a social planner, say, the government, cannot alter an inefficient outcome due to constraints such as funds, natural resources, etc.

For example, a government may be unable to provide housing to all citizens without compromising the living conditions of others due to insufficient funds.

Although the lack of housing is inefficient, it is still constrained PE because it cannot be improved without making others worse off.

Fractional PE

It is relevant when deciding on a fair allocation for indivisible or discrete items. A discrete grant is said to be fractionally Pareto efficient if there is no other discrete or fractional allocation that Pareto dominates.

PE is strengthened in terms of an equitable item distribution by Fractional PE.

In this way, every fractionally PE outcome is optimal, but not every Pareto optimal result is fractionally PE.

Ex-ante PE

It implies that the outcome generated by a stochastic process is Pareto efficient in the context of expected utilities.

In other words, there is no different lottery that does not adversely affect other agents while giving at least one agent a higher level of expected utility.

Pareto Efficiency and Equity

A common misconception when first learning about Pareto Efficiency is that it implies fairness or equity.

However, it is important to note that simply because an outcome is Pareto efficient does not necessarily mean it is fair for all involved. It merely means that all resources in the economy are efficiently allocated.

Suppose Georgia has a basket of 30 oranges. She can distribute the oranges among three friends: Nikita, Tanvi, and Joey.

An equitable outcome would be to give each friend the same number of oranges, i.e., each friend gets 10 oranges.

However, even if Georgia decides to give 15 oranges each to Nikita and Tanvi and no oranges to Joey, the outcome would still be considered Pareto efficient.

This is because Georgia made both Nikita and Tanvi better off without Joey having to lose anything. Joey did not have any oranges, so not giving him any oranges did not reduce his inventory.

Yet, it would be unfair to exclude the third friend and give the first two more than what would be considered an equal distribution.

In this way, an optimal allocation of resources may not necessarily be what is best for overall social welfare.

Hence, when implementing policies, the government should factor in social efficiency, total welfare, as well as the diminishing marginal utility of money, etc.

Limitations of Pareto Efficiency

As easy as the concept of Pareto Efficiency is to understand, it has drawbacks that have warranted criticism from economists. The following section discusses some of these shortcomings.

- Distribution Of Resources: Pareto efficiency does not consider the real-life factors that come into play when distributing resources. The concept's condition is that "any change would result in at least one individual being worse off," which will lead to inadequate resource distribution.

- This may lead to socio-political unrest and inequality among communities.

- Externalities: One of the Pareto optimization assumptions is that all the costs and benefits attached to the phenomenon are internal. However, in reality, a number of external factors may impact costs and benefits, leading to sub-optimal decisions.

- Achievability: In the case of public goods, where external interventions might be necessary for efficient resource allocation, here the market mechanism may not be sufficient to achieve Pareto optimization.

- Social Desirability: In Pareto optimization, the allocation of resources may benefit one and harm the other, which doesn't align with societal values of equity and fairness. The phenomenon does help maximize total welfare but fails to consider how the wealth shall be distributed.

- Equity And Social Welfare: The equal distribution of wealth is the aspect that Pareto optimization where it makes no judgment. An income distribution could be Pareto-optimized but also may not maximize overall welfare. This will lead to ineffective and inefficient utilization of resources, yielding sub-optimal results.

In conclusion, the Pareto Efficiency highlights the importance as well as the challenges attached to the optimal distribution of resources. These limitations aid in understanding the wider societal implications and fairness when evaluating economic efficiencies.

Free Resources

To continue learning and advancing your career, check out these additional helpful WSO resources:

or Want to Sign up with your social account?