Bear Call Spread

Options strategy that requires multiple legs.

What Is a Bear Call Spread?

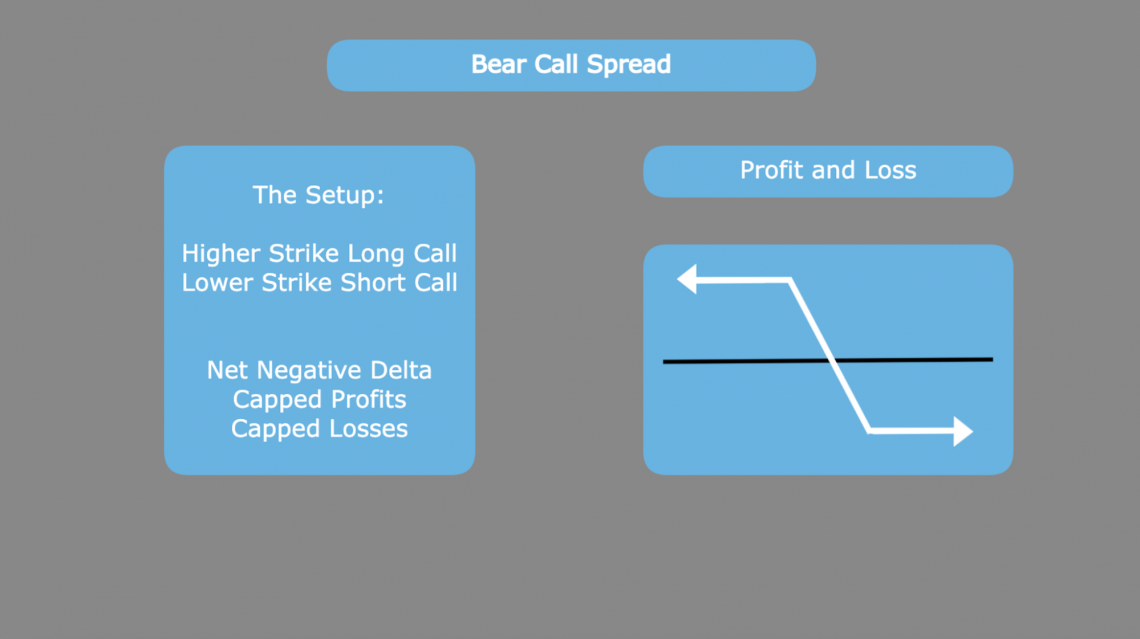

A bear call spread is an options strategy that requires multiple legs. It involves buying and selling a call option at two strike prices that expire on the same date. The bear call spread is considered an advanced options strategy.

In this specific type of call spread, the investor's long call option is at a higher strike than their short call. Therefore, the premium gained from the trade is the difference between the premium collected for selling the short-call option and the premium spent on the long-call option.

Because investors see returns as long as the short call is not too far in the money, choosing this strategy demonstrates a mildly bearish outlook on the underlying stock. It can also be said that the spread as a whole has a net negative delta.

This strategy shares some similarities with a naked call, which also hopes to collect a premium from a fall in stock price. The bear call spread, however, allows the investor to limit the risk associated with the short position and, in turn, lowers the premium collected.

Investors can think of the long call leg as strategic because it lowers the maximum loss on the trade.

This is because the investor has an asset in the form of a long call that increases as the price of the underlying increases. The long call shares can be used to cover the obligation of the short call, much like in a covered call.

By purchasing the long call option as a hedge against the potential losses of the short call, the investor profits less from the passage of time, which would help decay the value of the short position. This, in turn, raises the break-even point when compared to a simple short call.

Furthermore, the premium paid for the long call option lowers the max profit. With a typical short call that expires worthless, the investor can exit the position with the full premium of the contract sold.

This is not the case with a bear call spread. The long call cuts into the premium earned from the short call, reducing the spread's maximum profit.

The main things to remember about the bearish version of a call spread are the following:

- The strategy reflects a mildly bearish outlook

- The strategy allows the investor to collect a premium for selling the call spread

- Both losses and profits are capped

Relevant Options Details

Investors must understand the core components of options contracts when trading using advanced options strategies such as spreads. However, beyond just the basics, this strategy hinges on a solid understanding of the options of the greek delta.

For any given options trade, there is both a long and short position. For a given call option, these two positions have the following rights and responsibilities:

- Long position - right to buy

- Short position - buying/fulfillment obligation

Traders on the buy side of a call option pay a premium to purchase the contract. Ownership of the contract gives the right to buy 100 shares of the underlying security at the strike price at or before the expiration date.

On the sell side of the trade, the seller writes the contract and collects the premium from the buyer. In return, they take on the risk of the trade.

In this case, the risk is a fulfillment obligation to the buyer. This would be selling the shares of the underlying stock to the buyer of the contract for the specified strike price up until the contract's expiration date.

Because the bear call strategy involves buying and selling call options at different strike prices, each leg of the contract gains or loses value at different rates.

In an option contract, the Greek delta tells us how much the premium of the option contract changes for each dollar shift in the price of the underlying stock.

Call options have a positive delta, and put options have a negative delta. That is because call options gain value with a rise in price, while put options decline in value with a price rise.

For options contracts sold, we reverse the delta. This is because the goal for sellers is a worthless contract expiration. Therefore, increasing the premium would mean repurchasing the contract and closing the position is more expensive.

We look at the net delta for an option contract with multiple legs, such as the spread we created. This tells us how the price of the spread overall changes concerning the change in the underlying.

Because the long call position has a higher strike, the delta will have a lower magnitude. Therefore, for call options, price increases in the underlying have a greater probability of impacting the lower strike option than the higher strike option.

As we can see in the option chain for VOO, strikes closer to the last price of 375.21 have a higher delta than the highlighted 400 strikes Oct 21, 2022 call option. This highlighted call has a delta of .25. As the strike moves closer to the underlying price, the delta increases.

Because the second leg is a short call, we reverse the delta sign and are left with a negative value for this leg. However, because this strike is lower, it will always be closer to the money or more in the money than the extended position.

This means that when we add the two deltas together, the short-call negative delta outweighs the long-call positive delta. Therefore, the resulting spread has a net negative delta. This means the spread gains value overall as the underlying stock price declines.

Bear Call Spread Example

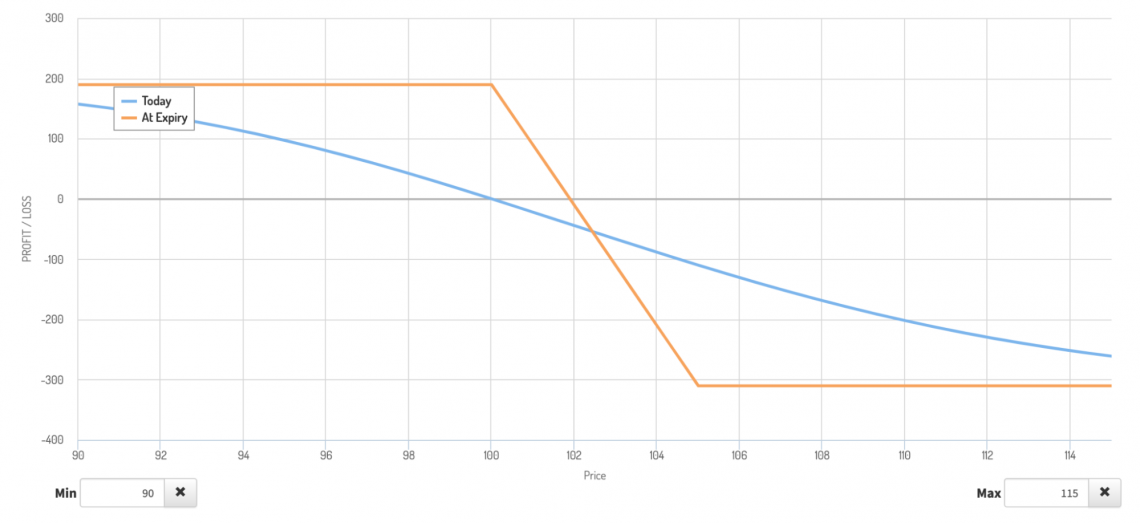

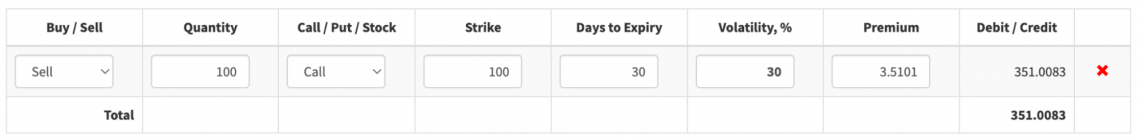

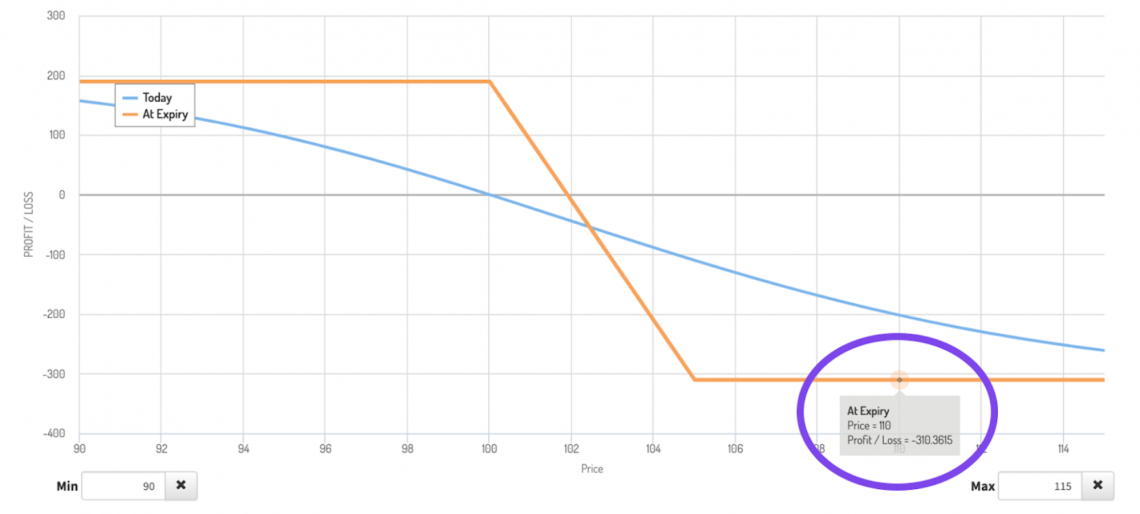

In this example, bear call spread, the investor is selling a call at the 100 strikes and purchasing a call at the 105 strikes. Both options expire in 30 days, and the pricing model assumes implied volatility of 30. The current price of the underlying is $100.

As we can see, the short position earns the investor around $351.01 in premiums. Subtracting the $161.37 from the long call position purchased to hedge risk, the investor has credited a net of around $189.64.

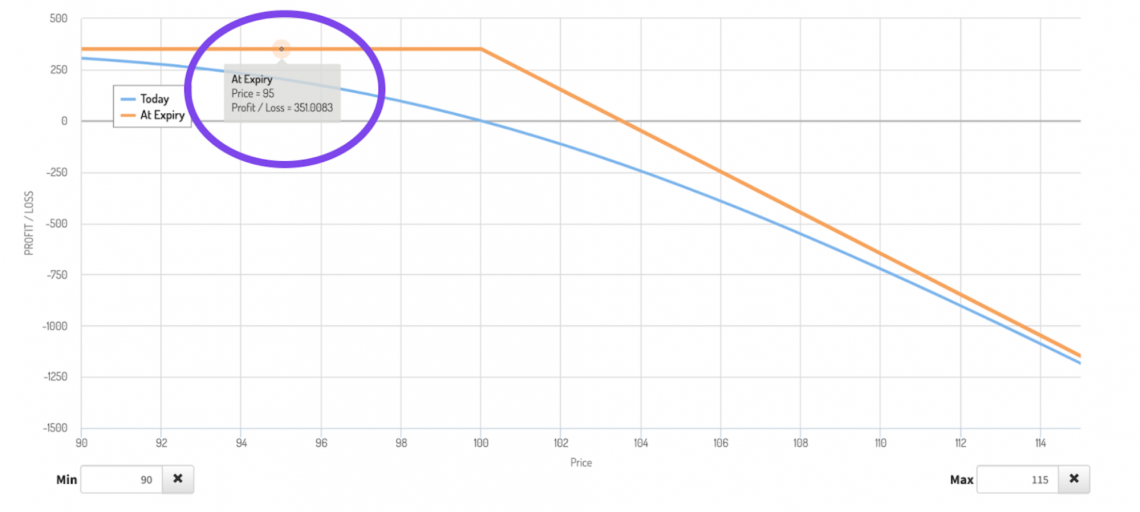

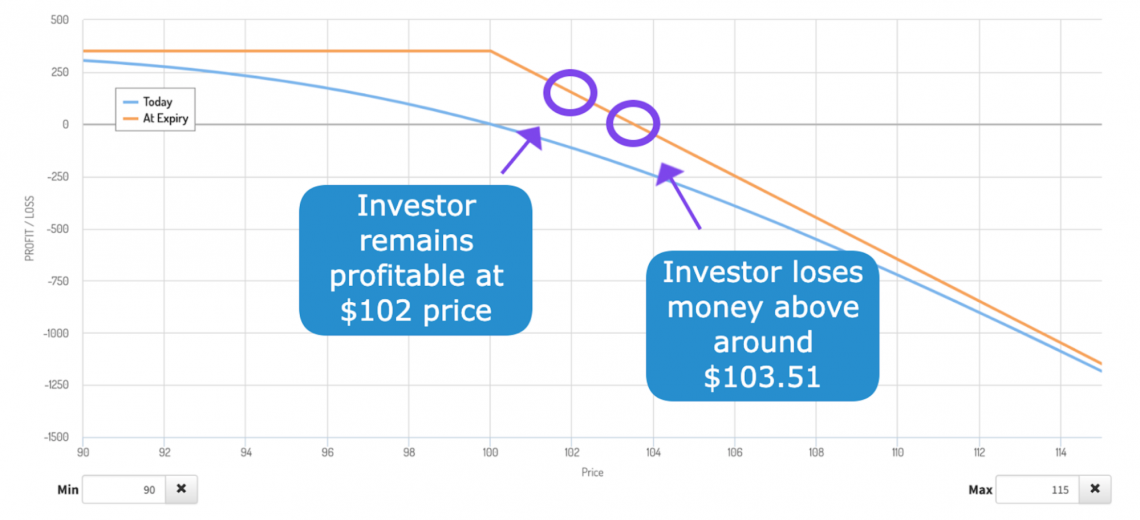

Looking at the profit and loss graph, the bearish sentiment is clear. However, the investor remains profitable if the stock price stays below $101.89. The premium collected gives the investor some buffer below the upper strike price.

Generally, the amount the stock can rise above the short call strike before the investor takes a loss is equal to the premium expressed per share. The premium is 1/100th of the total cost of the contract, as the contract represents 100 shares of the underlying.

For this example, the stock can rise by $1.89, as the original contract price was $189.

Break Even = Short Strike + Net Spread Premium

The premium also determines the max loss and considers the distance between strikes.

Max Loss = (Short Strike - Long Strike) x 100 + Net Spread Price

Finally, The max profit also relates to the premium, as the premium determines the amount the investor earns from writing the spread.

Max Profit = Net Spread Price = Premium x 100

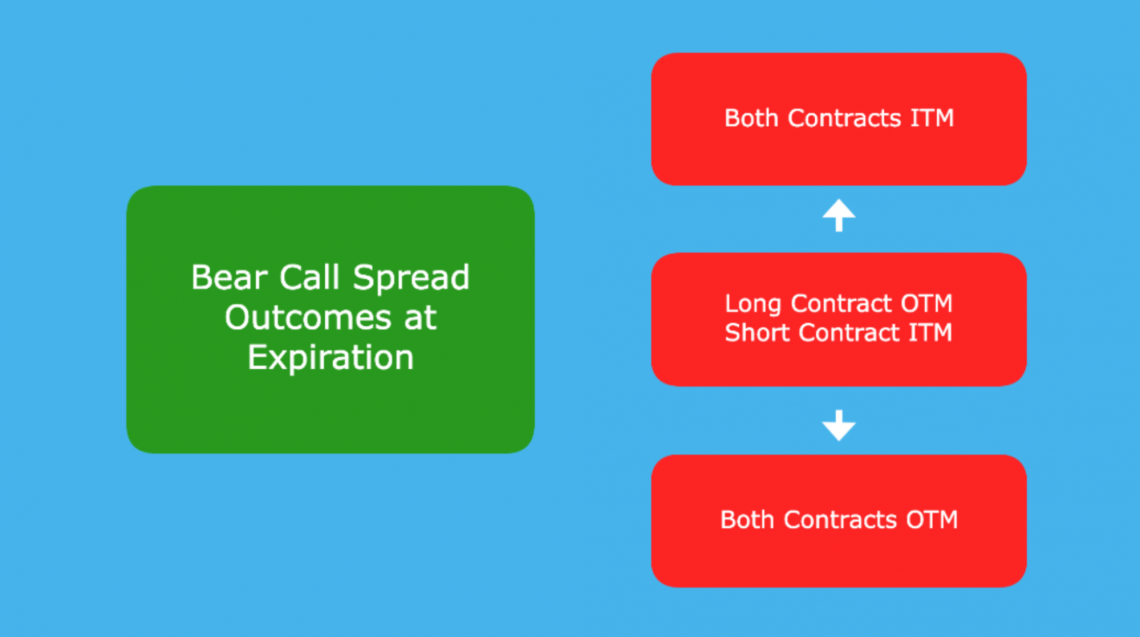

We can see exactly why each of these specific price points makes sense by looking at different expiration price scenarios.

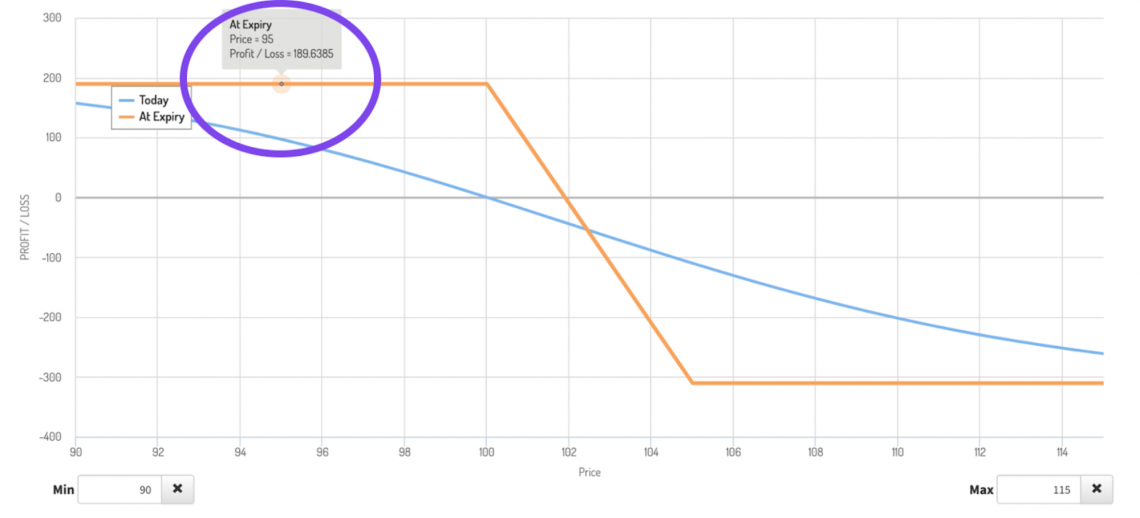

Consider a situation where the price at expiration drops to $95, meaning that it is above the strike price of the short position.

The investor’s long position expires worthless, and it is not exercised. The investor’s short position also expires worthless. It is not exercised. The investor is left with the premium collected originally from selling the spread, around $189.64.

As we can see, this profit is less than that of a naked call, which would be an alternative bearish setup the investor could construct while being able to collect a premium. This reduced profit is explained by the reduced downside, which equates to less risk in the position.

Instead of having around $351 from selling the short position (as shown in the graph), the investor has their premium reduced from buying the 105 calls.

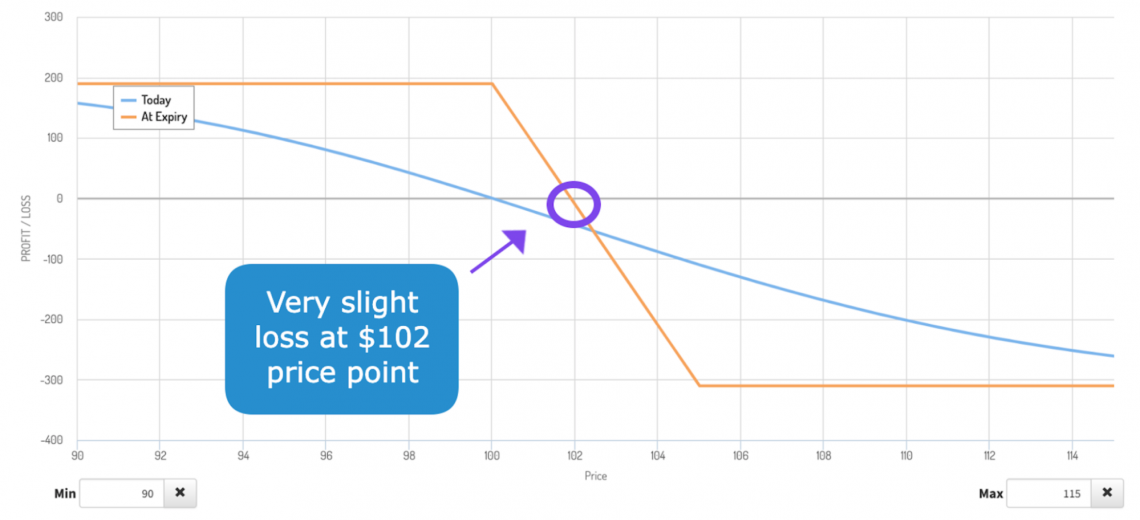

Another possibility is that the underlying strike price at expiration is between the two strikes, in this case, between 100 and 105. So let us say the closing price is $102.

In this situation, the short is in the money and, thus, is exercised. As a result, the investor is liable for 100 shares at the $100 price.

The long call is out of money, so the investor has no reason to exercise it. Instead, the investor can sell those shares at the market price of $98. The investor loses $200 from the 2-dollar price difference.

Because the investor initially collected $189.64 from selling the spread, their loss is only around $10.36.

Compared to the naked call counterpart, the investor using the bear call spread is again less profitable. If the investor had only sold the 100 calls, they would have broken even on the trade.

The collected premium with a naked call would be more significant and enough to cover the market price and strike price differential at expiration.

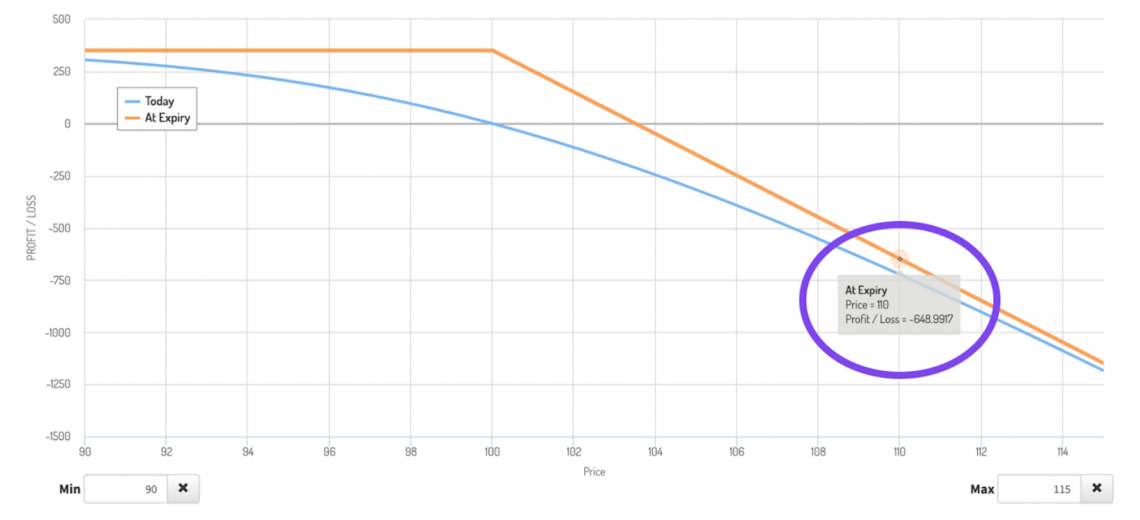

The outcome is one where the underlying market price is above the long call strike, in this case, above $105. Let us assume that the market price is $110.

Because both calls are in the money, they are both exercised. For the investor who sold the spread, the extra premium sacrificed was worth it to hedge the downside of the short-call leg.

The short call is exercised, meaning the investor must buy 100 shares at the $100 price point. Because the investor purchased the $105 call, they also have the right to buy shares at $105.

The investor exercises their $105 call and sells those shares at $100 to fulfill their short call obligation. This loses the investor $500. However, when the investor considers the premium collected, they are left with only a loss of $310.36.

The thinking is the same at any point above the long call. The investor’s losses from the short call are offset by their returns from their long call. Any difference in price leaves them with the same $310.36 loss.

For this reason, we say the investor has a limited downside. This is highly advantageous compared to a naked call position at certain price points, as the naked call has the potential for unlimited losses.

In this case, the short-call counterpart would have lost more, around $648.99.

Final Considerations

As we can see from the above profit and loss comparisons, the bear call spread is strategic in that it lowers a trader's maximum loss with the sacrifice of smaller profits and higher break-even points compared to a naked call setup.

Because extreme price movements are less common than smaller price movements, the profitability of a bear call spread may be typically less than a naked call. However, it is crucial to remember that the risk is also much less.

Although the investor has a long protective call, they have to consider increased risk and responsibility for having a short leg in their investment strategy compared to just holding shares or purchasing options.

While it is true that the long call position hedges the risk associated with the short position, the possibility of an assignment before the expiration of the option is possible.

This is most notable in cases where the underlying stock has a divided payment scheduled before the expiration of the call contract. If the time value remaining in the contract is less than the expected dividend, the contract holder may choose to exercise to collect the dividend.

If the investor holding the spread is not paying attention, they may not realize that the assignment is likely. Forgetting to close their position by closing the entire spread or repurchasing the short leg (leaving the long position open) leaves an investor with fulfillment obligations.

In this situation, a long position is created on the investor's account. Shares must either be repurchased to close this position, or the long call must be exercised. In some cases where the trader is using margin, a margin call could be triggered, leading to an account liquidation.

These extra considerations and the complexity associated with price movement are important reasons why this strategy is recommended for advanced traders.

Many brokerages will not allow investors to use this strategy without first verifying the investor’s familiarity with options and other financial information.

As with all options strategies, a greater risk is associated with increased leverage when using a bear call spread. Beyond just understanding the setup, investors should have an understanding of equity valuation based on fundamentals.

Due diligence on the underlying and a strong conviction of price movement is a must-have when using strategies susceptible to extra volatility.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?