Are some Monopolies more Beneficial for Consumers?

I was talking with a friend the other day about streaming services, and we felt like consumers these days are significantly worse off than the days when you really only needed to subscribe to Netflix, despite Netflix operating somewhat like a monopoly in the digital streaming space when this was the case.

My argument was that before you had Disney+, HBO Max etc., you only needed to subscribe to one service which arguably had more options of stuff you actually wanted to watch, and was priced lower than it is now. With the entrance of new streaming services in the mid-late 2010s, the space became more fragmented, and I think the consumer is worse off having to pay for 3+ streaming services to watch the same selection of good quality movies/shows that they got for $12/month back in 2015. Additionally, I think that the main way that all of these streaming services try to differentiate themselves is to create original content, which (in my opinion) is often subpar and excessively expensive. I feel like the rise of original content as a result of industry fragmentation has made things even worse for the consumer, as these services need to pass on these production costs to consumers through subscription price hikes to keep the lights on. Thus, you have increased prices per service, in addition to lower/worse optionality, meaning that even consumers that only stick to one service become increasingly worse off than the days when you could watch Disney movies, NBC shows, and original content all of Netflix.

Outside of streaming, I feel like the idea that the modern consumer benefits from a monopoly is applicable to some other industries. For example, I think consumers would be worse off if there were 2 similarly popular football or baseball leagues in the US (with what would probably be lower quality teams than in the NFL & MLB) that they needed to pay separate packages to watch, or how the introduction of Threads drawing some people away from Twitter (for like a week) made access to the information that you could find on Twitter more difficult since you had to go to two different platforms.

With the observations above, I want to make the case that in industries with extremely low variable costs per sale/product (i.e. the only per consumer variable cost for movie/sports streaming packages & social media accounts is server capacity costs and more customer service reps (+revenue sharing in NFL/MLB)), and where most expenses are not tied to each unit sold (overhead and basic operating costs, movie production), consumers are better off under a monopoly due to not having to pay more in production & operating costs for slightly differentiated but largely redundant products.

Not sure if this post is relevant to WSO, but please let me know if you have any thoughts or criticisms, as my ideas are a bit rough since I'm still a student. I understand that in general (or at least based off of what I'm taught in college) that monopolies are generally disadvantageous, and I'm not the biggest fan of the amount of M&A that exists these days, I just thought this was something that I wanted to hear other opinions on. Thank you for reading all this as well!

For a time, yes. But then the monopoly realizes the power it has and it stops being better for consumers.

Thanks for the comment! Could you not make the case that for monopolies in entertainment, there would be enough competition from other sources of entertainment that these monopolies would still need to offer competitive pricing and products in order to survive (and you could maybe extrapolate this point to other goods that are "wants" instead of "need")? For example, I remember reading about a Netflix earnings call sometime back in early 2019 where their CEO said that in terms of competition, they were most worried about video games and companies such as Epic Games diverting their customers attention away (which logically means that they would need to keep pumping out entertaining content at affordable prices to retain their customers). And I don't think that baseball fans really suffered from the merger of the AL and NL, and if anything, I think that the merger of the AFL and NFL was probably advantageous for football fans (I wasn't alive then but I'd imagine that the average costs to watch an NFL game haven't outpaced the costs of other forms of entertainment over the past 50 years that the NFL has had a monopoly on football in the US). For non-essential goods/services I feel like the losers of a monopoly may be employees (athletes, writers, less tech jobs) but would consumers still not have enough optionality through different products to limit the power of the monopoly?

Just look at Uber's prices today vs. 5yrs ago and you have your answer

How would you stop a monopoly or duopoly from charging exorbitant rates? I remember my parents paying close to $100/month for premium cable - that was almost 20 years ago. With that you got a lot of content but with lower production quality. Now as a result of more competition and new technology, you get more content value as a customer and a better experience. You can get Netflix, Disney, HBO, Amazon Prime, Apple TV all for under $75. That’s a whole lot of content and you have choice in how much you want - you couldn’t tell your cable provider that you only want 50 channels or whatever and pay for only those. If we only had cable or just one streamer to choose from, I guarantee we would be paying more than $100 or see significantly less production quality or quantity vs. the current environment.

The only way a monopoly would benefit customers is if comparably there is a degradation of value vs. price to the consumer. I don’t see from the product value side and definitely not from pricing.

Great point! I definitely agree that entertainment monopolies were disadvantageous not too long ago, but I think the business models of cable companies differ significantly from the monopolies listed above and thus the effects of these monopolies may differ from back in the day. In the second last paragraph of the post, I said that my observations stood for industries with extremely low variable cost per sale/product, which I don't believe was the case with cable, as cable companies paid per-subscriber fees back to the network and thus had pretty high costs tied to each customer (in addition to installation and maintenance costs for each household as well). If you hypothetically removed the (what was, to be fair, a pretty essential) middleman and had households pay fees to each channel they wanted instead, could you not argue that the TV industry would have probably consolidated into a few networks that monopolized certain forms of entertainment (game shows, tv shows, sports, news) resulting in higher quality content for lower prices than what you had to pay to access 100+ (largely redundant) channels? Due to the wealth of different forms of entertainment available today (video games, social media, live-streaming, movies, live sports), as well as a major industry shift in which we see the producers of content being directly responsible for the distribution of that content as well (instead of middlemen such as cable companies being responsible for distribution), that the effects of a monopoly in some industries would be completely different now than even 20 years ago (I probably should have used the term "modern consumer" in the original post a bit more)?

You’re conflating things. The business model of many recent successful tech startups was to build critical mass by pricing at uneconomic levels / below marginal cost (Uber, Netflix, Food delivery) and so yes, customers received excess value, which gave the company ability to achieve critical mass, attempt to crowd out rivals / follower and hope to make money later.

Amazon was successful at this. The other companies I mentioned, not so much. They’ve all had to raise price significantly because the economics couldn’t persist as they were.

the areas that USA has decided regulated monopolies are ok is the utilities space. Large capital investment which is unlikely to be undertaken without confidence in taking 100% of the customer base in an area.

Great point and sorry if I'm just spitting out bs at this point but could you not make the argument that the unit economics of Netflix is significantly different than Uber/Doordash/Amazon, as Netflix only pays a licensing fee for outside content instead of paying per watch/delivery and thus has a significantly lower marginal cost? Thus, it wouldn't need to raise prices as much as the other companies to become profitable after it's grown its customer base to a large enough size?

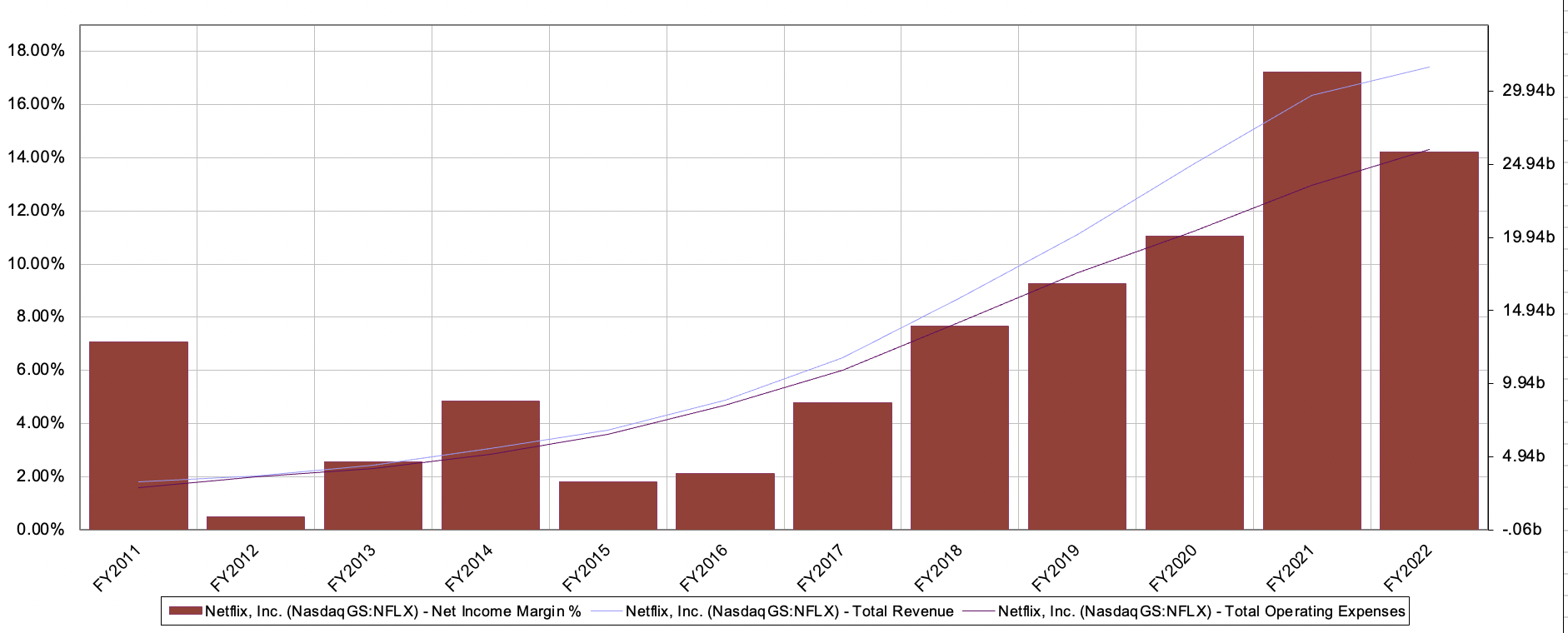

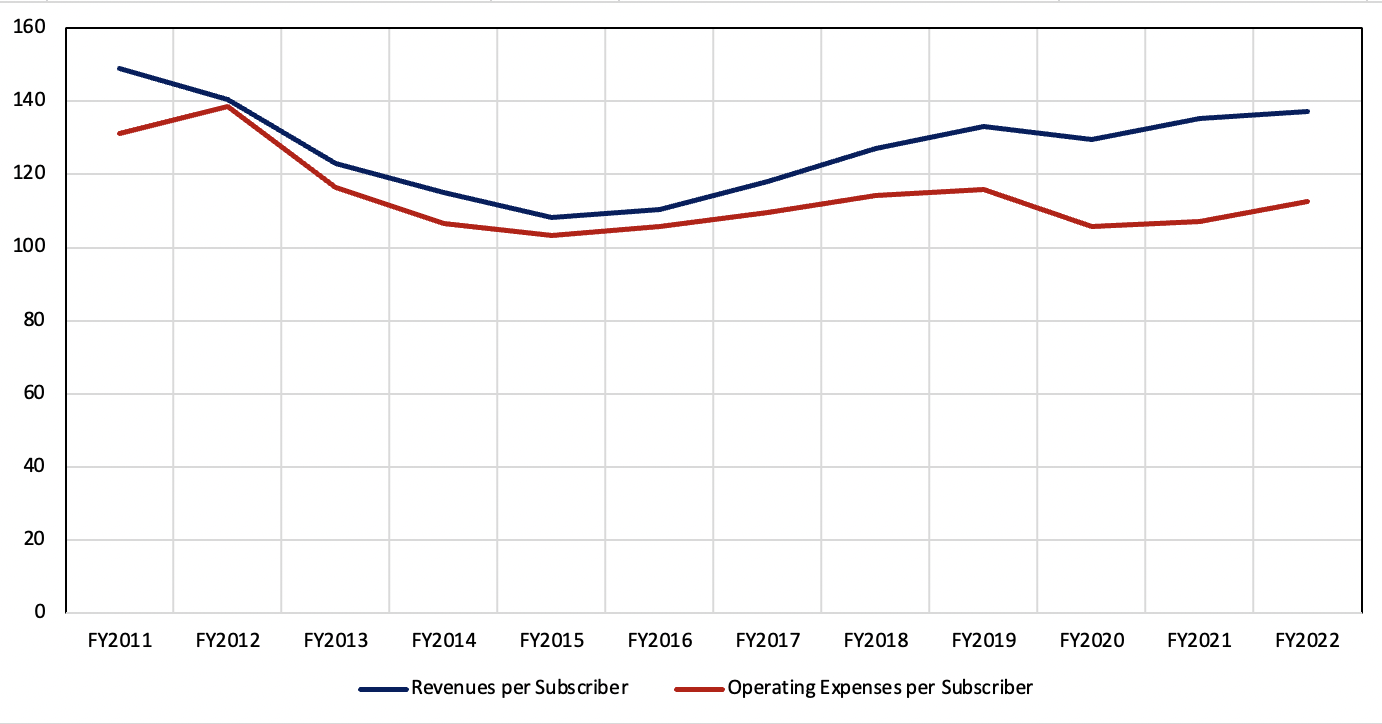

I feel like we already saw this with Netflix where the company was already profitable from 2012-2019 (so post-Blockbuster bankruptcy when it arguably became a monopoly) while simultaneously still pursuing an aggressive growth strategy. So it was still growing to build critical mass without pricing its service below marginal cost, and has already proven that this business model is able to grow its net income entirely through reducing operating expenses per unit instead of needing to raise prices.

It's not really expressed in the graphs above, but I feel like it's only really after 2019 (when Disney+ and other services began to gain steam) that consumers started becoming worse off (so again, much after Netflix was able to price its product above marginal cost). As seen above, revenue per subscriber has stayed relatively flat since, but I feel like Netflix's product has become increasingly inferior since, thus reducing the utility that each subscriber receives from a subscription (this is where my argument becomes tougher to model unfortunately). If I combined the income statements for all of the streaming services, I would assume that from 2018 onwards, revenue per consumer across the industry (defining the consumer as a person who has at least 1 subscription, so someone who has 3 subscriptions only counts as 1 consumer in the combined entity) would have exploded, along with operating expenses per consumer. But the overall utility that each consumer gets would not have risen significantly during that same time frame, thus making them worse off as they're still paying more overall?

I think a similar comparison to this would be social media where revenue increases with each customer (through advertising) but costs don't increase that much (server fees, creator funds).

I do understand that monopolies end up screwing someone over, and I think in the case of Netflix it probably would have been the studios who supplied it with content that would have lost, as Netflix's power as a monopoly would allow it to negotiate significantly lower licensing costs for movies/shows. But I think that consumers still have enough forms of entertainment available to them that Netflix would not be able to significantly raise prices without shooting themselves in the foot, and thus (again) would increase margins mainly by cutting costs. Thus consumers would have still benefited from the monopoly (which was my original argument), and producers would be worse off over the long term.

Sorry that this was a bit of a ramble or if it doesn't make sense, but I really appreciate the comment and thank you for helping me question and refine my (pretty uneducated) opinion as well!

Netflix was never a monopoly nor was it operating as one.

Netflixs competition wasnt other streaming services, but cable and the box office. Both of which were much stronger positions than they are today.

Netflix also wasnt able to leverage their size at the time to even be profitable, instead focusing on long term growth and customer acquisition.

Are monopolies good or bad for consumers? It depends.

Monopolies are always better for the market. Period end of story. What do I mean by this? Well let's take a look at the example provided, streaming services.

When the market was concentrated with just Netflix and Youtube, with Amazon having streamed rentals, consumers were able to view almost anything that they wanted on those two (three) platorms. We had a much better selecton of content of much higher quality. I fundamentally disagree with people who say that the competition has improved quality because it verifiably hasn't. I don't view HBO as a real competitor to the other streaming platforms because it really at the end of the day is just a premium channel package that it has always been just viewable on the internet now rather than only through a cable package.

The proliferation of platforms has created a bidding war for content which has driven up the price of content and the price of the streaming services. Thus increasing costs for consumers while significantly reducing content. It ironically is the exact same thing as the people who bemoan monopolies say will happen under a monopoly.

https://www.inc.com/alex-moazed/why-modern-monopolies-are-good.html

Why Modern Monopolies Are Good

Every business wants to have the riches of a monopoly, but no business wants to be called one. Here's how today's modern monopolies are being redefined by the platform business model.

"The way we think about businesses and the economy is outdated and marred by contradiction. No where is this contradiction more clear than when it comes to monopolies.

As an entrepreneur, everyone wants to own a monopoly. Meanwhile, investors clamor to gain entry into fundraising rounds where tech startups that are on the way to monopoly status. And as billionaire investor and Paypal founder Peter Thiel says, his number one piece of advice to entrepreneurs is: if you're building a company, build a monopoly.

Yet ask a business owner if they want to be labeled a monopoly, and the answer is almost always no. Every business wants to be a monopoly, but no business wants to be called one. That's because monopolies are considered bad. Thanks to their predecessors, monopoly businesses have a reputation for evil. And in many cases, rightfully so.

20th century monopolies like AT&T, Standard Oil, and RCA took advantage of consumers and stifled competition in their industries. Competition forces companies to keep consumers' best interests in mind. However, in the absence of competition, consumers fall victim to greedy monopolists. This is all true. When a monopoly controls an industry's entire supply chain, it's easy to keep out the competition. As Timothy Wu explains in his book, Master Switch, monopolies use a mixture of government regulation and supply chain ownership to shut out any competition.

Yet modern monopolies don't work the same way as their industrial-era forebearers. Now, this isn't because the executives of today's monopolies are better people. Respectfully, not many people would say that Steve Jobs was a nice person. So what's the key difference? Today's modern monopolies are platform businesses--and they don't own their supply chains. Instead, these businesses create economic and social value by building and managing massive networks of users. Rather than directly producing or selling their own goods or services, these companies simply connect people.

Examples of platform businesses include Facebook, Google, Apple, Alibaba, Uber, and even Snapchat. Driven by network effects, these businesses are capable of growing far beyond the limits of traditional, asset-based businesses. That's why platform businesses are rapidly taking over existing industries and creating entirely new ones.

But other than size and market dominance, today's titans of industry have little in common with the monopolies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Because these platform companies don't own their supply chain, they don't have the same ability as old, industrial monopolies to shut out competitors.

For example, at one point Standard Oil owned more than 90 percent of the production of oil in the United States--nearly all of the country's oil refineries. In other words, at Standard Oil's peak, no one else could even make a competitive product, let alone sell it.

This method of establishing market dominance contrasts starkly with how modern monopolies operate. Platform businesses grow not by acquiring more factories but by connecting more and more users within their networks.

Platforms become dominant not because of what they own but rather because of the value they create by connecting their users. They don't own the means of production, as industrial monopolies did. Instead, they own the means of connection. Standard Oil, Facebook is not.

While these platform companies do have significant market power in their industries, they don't control their users in the same way that Standard Oil controlled its sources of production. Alibaba can't just flip a switch and change the output of its sellers. It controls its market, but it does so only indirectly by providing value to its merchants and consumers.

Additionally, today's platforms are competitive in a way older monopolies were not. As a result, modern monopolies can rise and fall from the iron throne much faster than the industrial monopolies of the 20th century. For modern monopolies, life is less Downtown Abbey and more Game of Thrones. There's always a new competitor ready to cross the sea and steal your users.

For new tech startup founders and investors, that's great news. They can become billionaires and create the next great modern monopoly within a few years time. Look at Instagram founder Kevin Systrom, who sold his company for a billion dollars while it employed only 11 people. And Evan Spiegel, founder of Snapchat, turned down a $3 billion offer from Facebook at the age of 23.

For users, this competition is great news too. New platforms are creating entirely new categories of economic and social activity and value. Imagine trying to connect with your college friends before Facebook, connecting with celebrities every day online before Twitter or Snapchat, or selling your old belongings online before eBay.

In developing countries, where the infrastructure of commerce is less established, the contributions of platform companies are even more pronounced. For example, at one point, Alibaba's Taobao and T-mall marketplaces accounted for as much as 80% of China's ecommerce transactions. It wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that Alibaba (along with fellow Chinese platform companies like Baidu and Tencent) has built much of the core infrastructure of modern commerce in China.

Now, this is not to suggest that platforms can do no wrong. Regulators should (and do) pay close attention to these businesses to make sure they don't abuse their market power. But the types of regulations that worked for monopolies of old aren't likely to work for these modern monopolies. In many cases, platforms have very good reasons for governing their networks in ways that would traditionally be considered anti-competitive. In many cases, these kinds of platform policies are good for the network and for its users. Instead, regulators should be looking for areas where a platform's incentives diverges from that of its users. Otherwise, arbitrarily limiting the market power of these platform businesses will limit their network effects and have a negative impact on consumers.

Platforms are here to stay. The sooner we learn to embrace these modern monopolies' new way of operating, the quicker we'll reap the economic growth and benefits they bring.

Adapted from Alex Moazed's and Nicholas L. Johnson's new book Modern Monopolies: How to Dominate the 21st Century Economy, out now from St. Martin's Press. For more stories and commentary like this, please add me on Snapchat."

Only if the consumers have a share in the company

LOL no.

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/sarcasm

No, they're not beneficial.

The monopoly in the streaming space has harmed consumers because it has lowered the quality of content. The biggest movies during the last decade have been sequels and reboots, mostly from Disney (Marvel, Star Wars, Avatar, live action remakes, etc.). The high-grossing movies that weren't in this category were either directed by reputable directors or involved high-profile IP (Barbie, Nolan's Oppenheimer, Scorsese's Killers of the Flower Moon). The overall trend is that Hollywood has increasingly relied on brands and marketing hype to green light movies, not actually good content.

The reason for this? Streaming has made it too risky to take a chance on out-of-the-box, creative movie ideas because it's harder for studios to recoup their investments in them. So Hollywood's game plan for the past decade has been 1) acquire highly valuable IP, 2) hype the shit out of it before release, 3) make a bulk of box office sales opening night, and finally 4) move it right to a streaming platform afterwards.

This is not how it worked in the past. Before the streaming era, DVD rentals or expensive cable subscriptions were responsible for making a lot of independent movies commercially viable. Also, studios didn't predominantly rely on pre-release marketing hype to make a majority of box office sales in the opening night. Some movies like Back to the Future and Gone Girl made modest sums in their opening nights but picked up a lot of ticket sales in future runs because people were talking about how good these movies were. In other words, the hype for some of these older films was due to them being ACTUALLY GOOD MOVIES that people enjoyed watching, not movies that were hyped up before people even saw them.

Studios can't take this kind of creative risk anymore if streaming isn't a lucrative platform to make content. $20/month for unlimited movies is too good to be true. The bidding war for content, which drives up prices for content (and consumers), will lead to better prices for content creators which in turn will lead to more creative risk taking. I don't think movies like Pulp Fiction or The Shawshank Redemption could come out in today's era and make as much money as they made in the past. The higher prices in streaming are here to stay, and I think that's a good thing.

You think we have gone from competition to a monopoly in the streaming space?

Do you think there is more competition in the contnet space?

Do you have any idea why quality has fallen in the contnet space?

I think the answer is you have no idea what the reality is in any of these questions.

It depends. Some monopolies are definitely beneficial. Some aren’t. It is a relatively fact-dependent analysis that you need to do

My local wifi monopoly charges me $114/month.

I'm at $85/mo for wifi. I live in an AT&T community. I don't have a choice.

Debitis pariatur a pariatur et dolorem quasi et. Vitae error at voluptatibus recusandae soluta. Exercitationem optio sint non dolor nam laboriosam dicta. Quia nesciunt quaerat rerum beatae occaecati dolore totam.

Omnis repellat nihil distinctio reprehenderit natus. Quibusdam et assumenda quae deleniti distinctio impedit et. Culpa unde vel numquam consequuntur beatae maiores reprehenderit exercitationem. Voluptas deleniti quis quis adipisci repellat.

Voluptas suscipit ipsam exercitationem voluptatem et dolore. Reprehenderit omnis dignissimos voluptas voluptate alias tempora alias officiis. Quisquam ullam quasi ut.

Rerum ut voluptate a officiis dolor. Quo quia aperiam iste tempore laborum optio enim. Quam laboriosam dolore quas tenetur exercitationem velit eaque. Sed doloremque accusamus quisquam atque incidunt.

See All Comments - 100% Free

WSO depends on everyone being able to pitch in when they know something. Unlock with your email and get bonus: 6 financial modeling lessons free ($199 value)

or Unlock with your social account...