Reserve Calendar Spread

A trading strategy using options that involves buying and selling contracts that are at the same strike price but expire on different dates.

What Is A Reserve Calendar Spread?

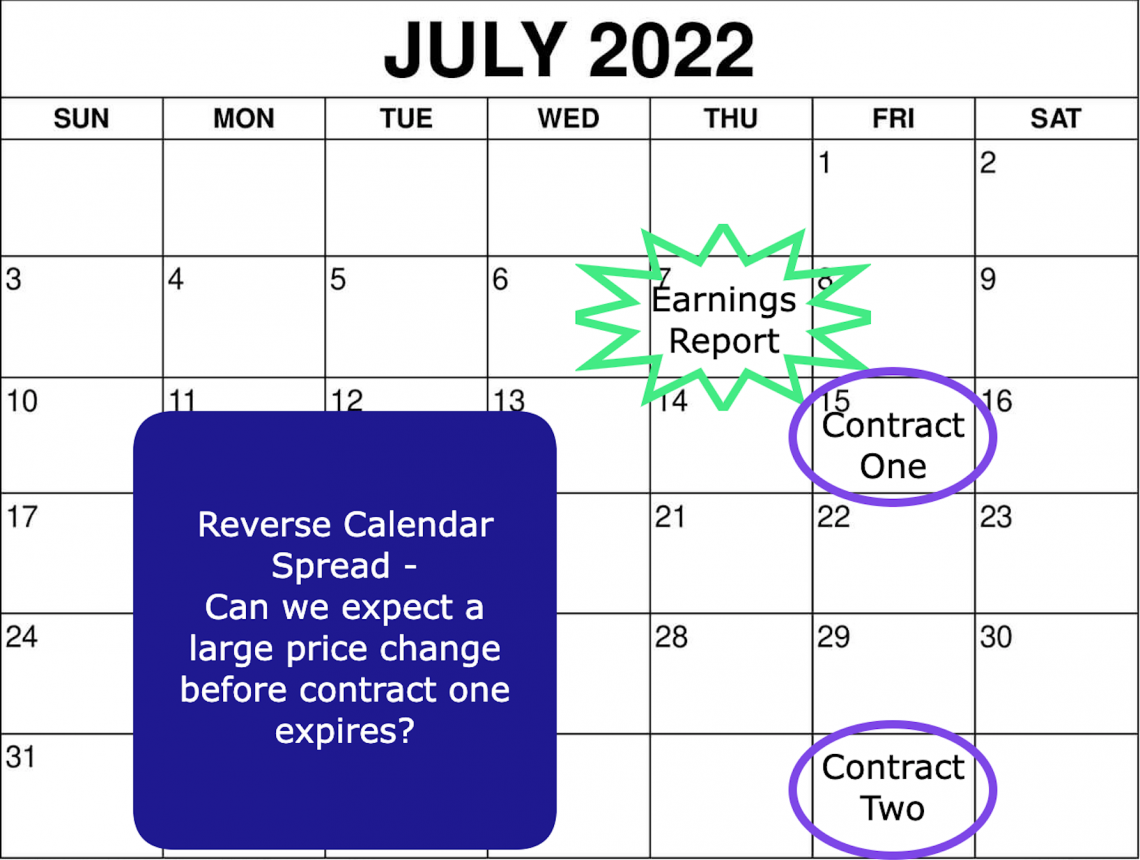

A reverse calendar spread, also known as a short calendar spread, is an options strategy that involves multiple legs. This strategy involves buying and selling contracts at the same strike price but expiring on different dates.

A reverse calendar spread is a strategy used by investors who think the price of a security will move away (in either direction) from the chosen strike price at expiration.

The strategy becomes less profitable the closer the underlying asset's price is to the strike price at the time of the shorter-term contract's expiration. In cases where the market price at expiration remains close enough to the strike price, the investor begins to incur a loss.

This strategy's profit and loss graph describe the shorter-term leg's expiration date. For a reverse calendar spread, this leg is the contract purchased.

When this leg of the option expires, the investor is left with a naked short position because their long option (which essentially acts as shares to cover the short) has expired. Therefore, closing the short contract at the expiration of the long contract is common.

Investors may also decide not to close the spread, leaving them to realize substantial losses if the price moves against their remaining short.

Traders can also think of this strategy as the counterpart to the calendar spread, which uses the same two option contracts but switches between bought and sold.

There are a few key components to remember about reverse calendar spreads:

- The investor should be confident about a price shift in either direction before the first leg's expiration.

- The investor collects a premium at open and must pay a premium to exit the position.

- The strategy is flexible; investors can choose not to close their short position if they want to keep all the premiums collected originally.

Key Takeaways

- A reverse calendar spread is an options strategy involving the purchase and sale of contracts with the same strike price but different expiration dates, used when expecting a significant price move away from the strike price.

- Profitability in this strategy depends on the gap between the underlying asset's price and the strike. As the price approaches the strike, potential profits decrease, and losses may occur.

- Initially, the investor holds a long position, but when the long contract expires, they are left with a naked short position, potentially incurring losses.

- Reverse calendar spreads require advanced options knowledge and are commonly used by institutions due to their complexity.

Options Rundown

An investor must understand the core components of options contracts to use advanced spreads effectively. This strategy specifically profits on differences in implied volatility and time value.

At a basic level, there are two types of options contracts. These include:

- Call options - right to buy

- Put options - right to sell

A call option gives the contract owner the right to buy 100 shares of the underlying security at the strike price at or before the expiration date.

A put option gives the owner the right to buy 100 shares of the underlying security at the strike price at or before the expiration date.

The seller of the contract has fulfillment obligations. They either sell shares or purchase them from the contract owners if exercised.

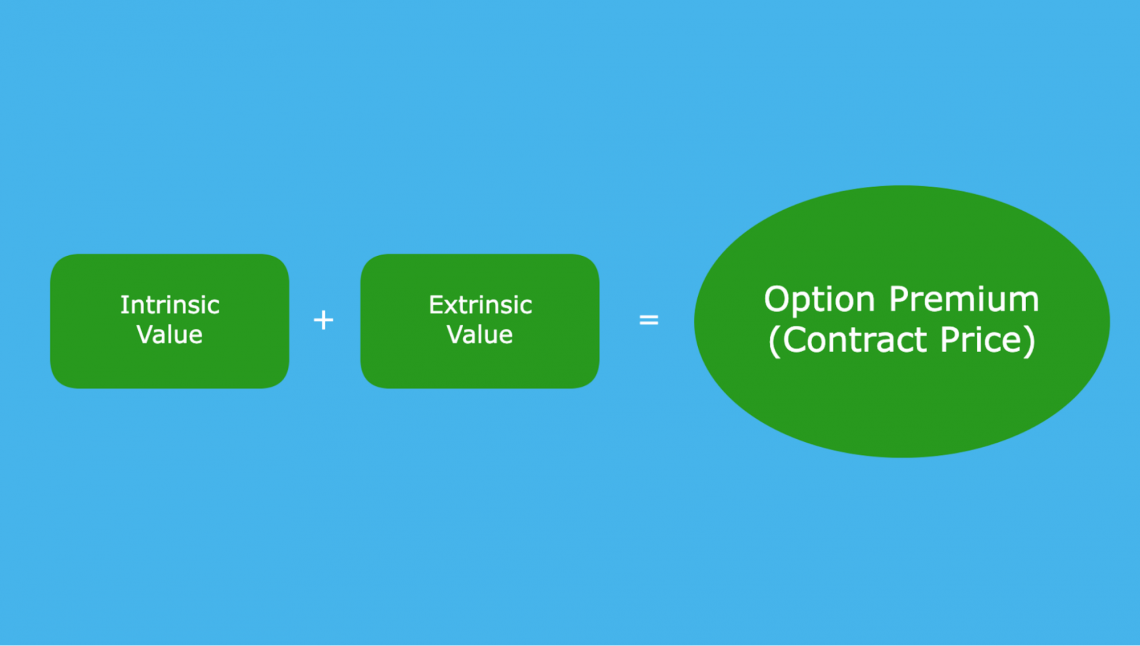

The premium gives an option contract's value, which is both the price to buy and sell (these may vary a little from the brokerage spread) the contract.

The value of the contract can be divided into two components, its intrinsic value and extrinsic value.

The intrinsic value is based on how much the contract would be worth if exercised on that day. For example, if the market price of a security was $107 and the strike price of a call option was $105, there would be $200 of intrinsic value, as one option usually controls 100 shares.

The extrinsic value is the difference between the option contract price and its intrinsic value. For example, if the contract price were $300, the extrinsic value would be $100.

Extrinsic value is important because it considers the possibility of price movement. The extrinsic value drivers are the time until expiration and the implied volatility.

- More time before expiration means a greater opportunity for price movement. This can change the contract's moneyness (whether in-the-money, out-of-the-money or at-the-money) and is, therefore, accounted for in the contract's price.

- Similarly, implied volatility changes the possibility of the contract expiring in the money. If the underlying has more price volatility, there is a higher chance of big moves and, thus, a higher chance of the contract expiring in the money. This is also accounted for in the contract price.

For calendar spreads, the difference in extrinsic value is the key to determining profitability. The maximum profit is realized when the short contract expires worthless, but the long-term contract's extrinsic value is maximized.

What is important to realize is that extrinsic value is highest when the underlying is close to the strike price. For example, for the 165 call option on AAPL expiring August 19, 2022, the intrinsic value is 3.025.

At prices where the underlying is far below the strike (or far above for puts), there is little extrinsic value because it is unlikely that the contract will expire in the money.

At prices where the underlying is far above the strike (or far below for puts), a greater portion of the option contract is driven by intrinsic value. The time value of the option contract is less relevant because the contract is already in the money.

Because both options in this type of spread are at the same strike price, their intrinsic values will always cancel out. The difference in contract value is, therefore, the difference in extrinsic value.

Because extrinsic value becomes less of a value driver for extremely in/out-the-money contracts, being further in/out of the money lowers the value of the spread overall.

Reverse/Short Call Calendar Spread

The call-focused reverse calendar spread involves buying a shorter-term call option and selling a longer-term one at the same strike price.

At the beginning of the strategy, the investor collects a premium. The net premium to the investor is the difference between the premium collected from selling the longer-term call option and the premium spent purchasing the shorter-term call option.

Recall that both options are at the same strike price. The difference in their value is driven by extrinsic value.

Because the longer-term short call has a greater time value than the shorter-term long call, the premium collected from selling the longer-term contract is greater than the premium spent by the investor when purchasing the shorter-term contract.

This leaves the investor with a net gain, or a credit, in their account.

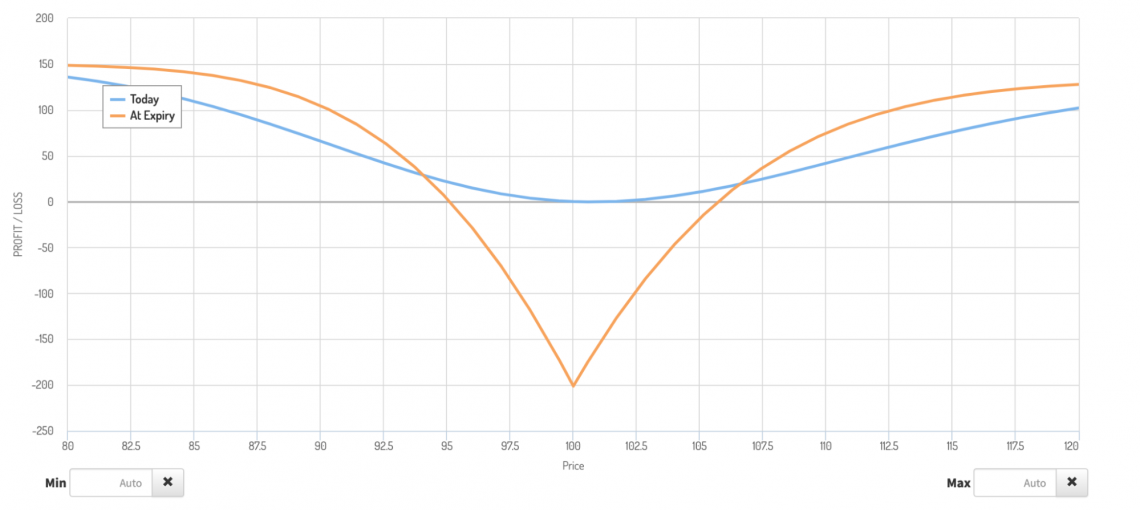

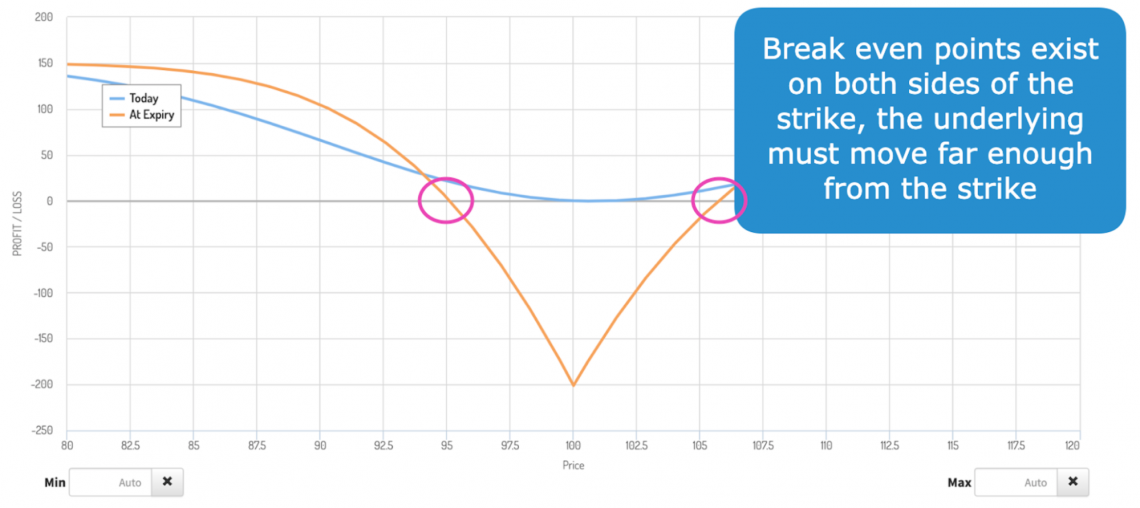

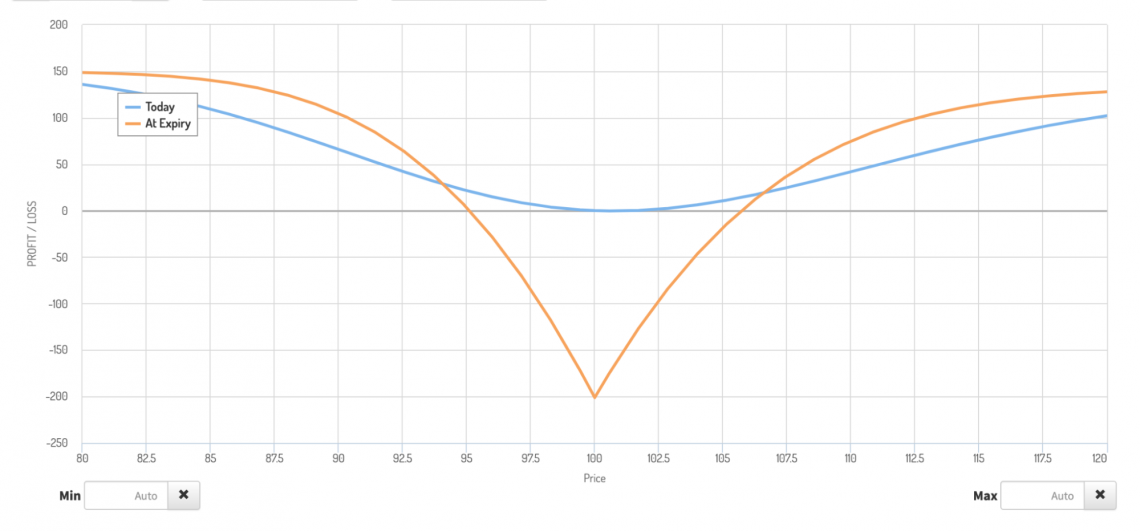

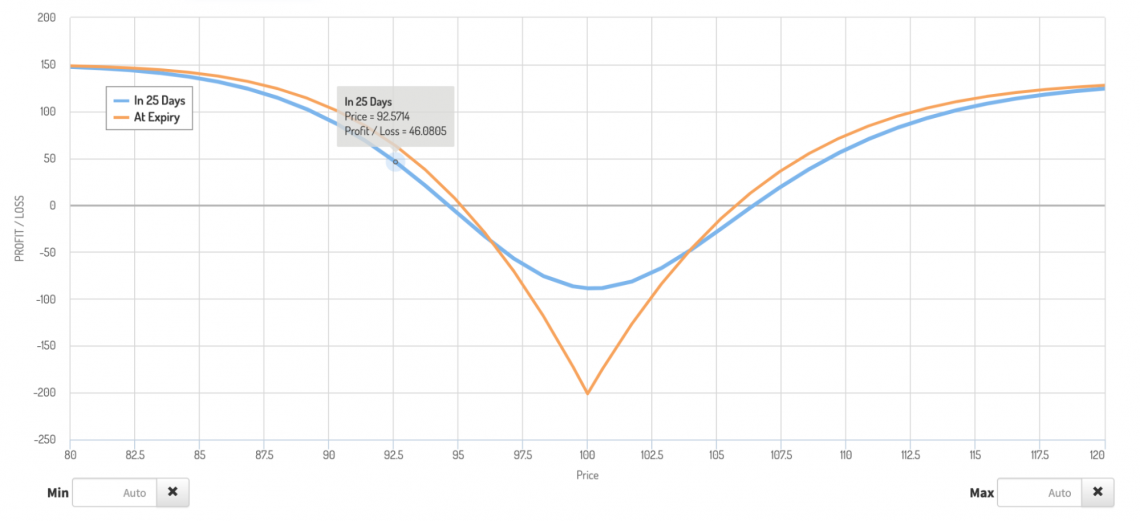

If we look at the profit and loss graph of the short call calendar spread, we can see that profit is maximized when the underlying moves sharply from the strike price.

In this situation, the difference in price between the two contracts will be very small. This spread, which the investor must pay to close, is less than what was initially received for selling the spread. This leaves the investor with a net gain.

The closer the underlying price is to the strike, the smaller the investors remaining profit from closing the position will be. Furthermore, the investor is at a loss at prices close enough to the strike. Why is this the case?

If the price of the underlying moves up or down away from the strike, the two contracts will gain and lose value simultaneously. This is good for the investor because they hope that the spread, or price difference, between the contracts is as small as possible.

The remaining spread will cut into investor profits at the expiration of the long position (the shorter-term contract), assuming that the spread is closed. This is what the investor has to pay to close their position.

Because this strategy involves two legs expiring at different dates, it gives the investor a window of flexibility to try and increase profits or reduce losses.

Instead of closing the spread at the expiration of the first contract, the investor can choose to leave the short position open. However, this exposes the investor to unlimited risk if the price of the underlying sharply jumps (they no longer have the long call to cover their position).

A declining underlying stock, however, will allow the investor to collect the remaining premium on the short call.

This means that the actual maximum profit situation would be when the first call expires in the money, allowing the investor to profit in the long position. Then the price declines later, meaning the short position expires worthless, and the investor keeps the full premium collected.

Reverse/Short Put Calendar Spread

The short put calendar spread involves purchasing a shorter-term put option and selling a longer-term put option at the same strike price.

Like the call version of the strategy, the investor collects a premium equal to the net difference in contract premiums from selling and buying.

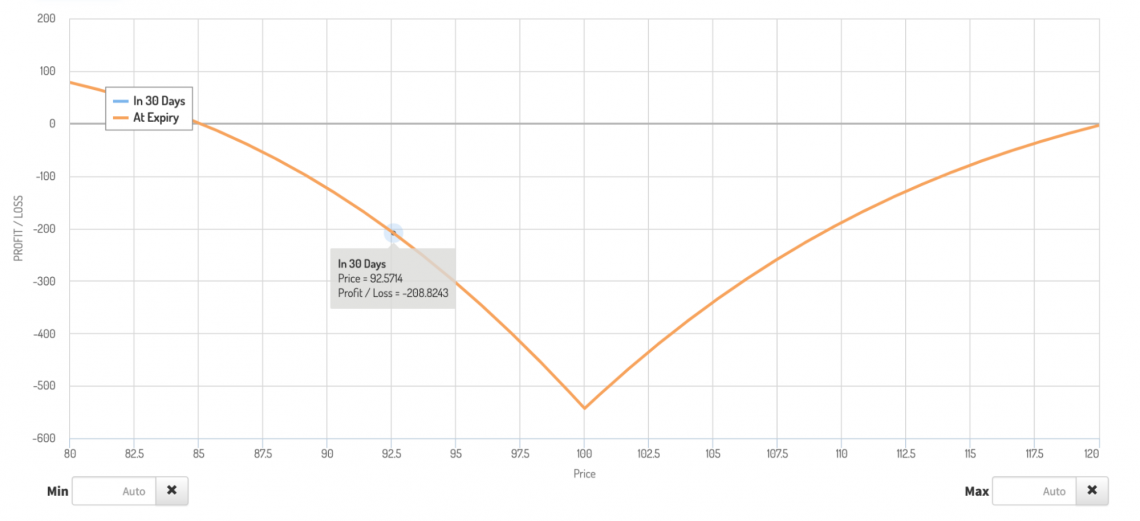

Once again, profit is maximized for the short put calendar spread when the underlying is far from the strike price. The difference in value between the long and short puts is minimized, meaning the investor can exit the position for cheaper and realize a greater profit.

As with the short-call counterpart, the expiration of the first contract does not mean the spread is automatically closed. Instead, the investor must close their short put by repurchasing the contract.

Investors that now expect bullish price movement may opt to hold onto their short put rather than closing their position. Rising prices would lower the value of the remaining short put, which would mean a less high exit price.

The value differences in contracts that create a spread in contract price work in the same way as the short-call version of the spread; however, the directions are switched.

As prices decrease, both contracts will be in the money. Because the value of these contracts becomes increasingly dominated by intrinsic value, they approach parity, and the spread loses value.

If we look at the profit and loss graph of the short call calendar spread, we can see that profit is maximized when the underlying moves sharply from the strike price.

In this situation, the difference in price between the two contracts will be very small. This spread, which the investor must pay to close, is less than what was initially received for selling the spread. This leaves the investor with a net gain.

The closer the underlying price is to the strike, the smaller the investors remaining profit from closing the position will be. Furthermore, the investor is at a loss at prices close enough to the strike. Why is this the case?

If the price of the underlying moves up or down away from the strike, the two contracts will gain and lose value simultaneously. This is good for the investor because they hope that the spread, or price difference, between the contracts is as small as possible.

The remaining spread will cut into investor profits at the expiration of the long position (the shorter-term contract), assuming that the spread is closed. This is what the investor has to pay to close their position.

In this situation, the investor may choose to leave the short position open, leaving the opportunity to profit both from the in-the-money long put and out-of-the-money short put if they think the underlying price will rise by the second expiration date.

On the other hand, as the underlying price increases, both contracts lose value. As a result, the spread once again decreases as both contracts approach zero.

In this case, the investor would most likely close the spread. There is little upside to holding a naked put, as there is only a little extra premium that the investor can realize by waiting for the short contract expiry.

However, a shift downward in price can leave the investor with the potential for big losses.

Reserve Calendar Spread - Final Considerations

For both the call and put versions of the reverse calendar spread, the strategy is heavily influenced by the passage of time. Therefore, the investor must realize that the passage of time without a shift in price will increase the value of the spread and the cost of exiting the position.

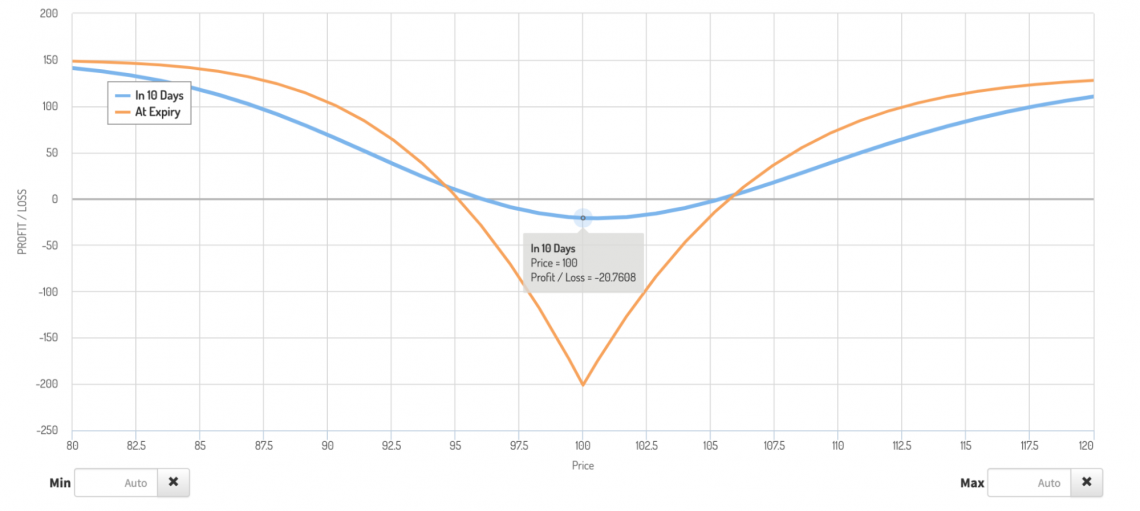

If we look at a time series of the price changes of the reverse call calendar spread we created earlier, we can see that losses slowly appear unless the price quickly shifts. However, if the price remains close to the strike for longer periods, unrealized losses exponentially increase.

As we can see, after just ten days, the price must have shifted to the side by a few dollars to avoid unrealized losses. After that, gains increase until expiration becomes nearer.

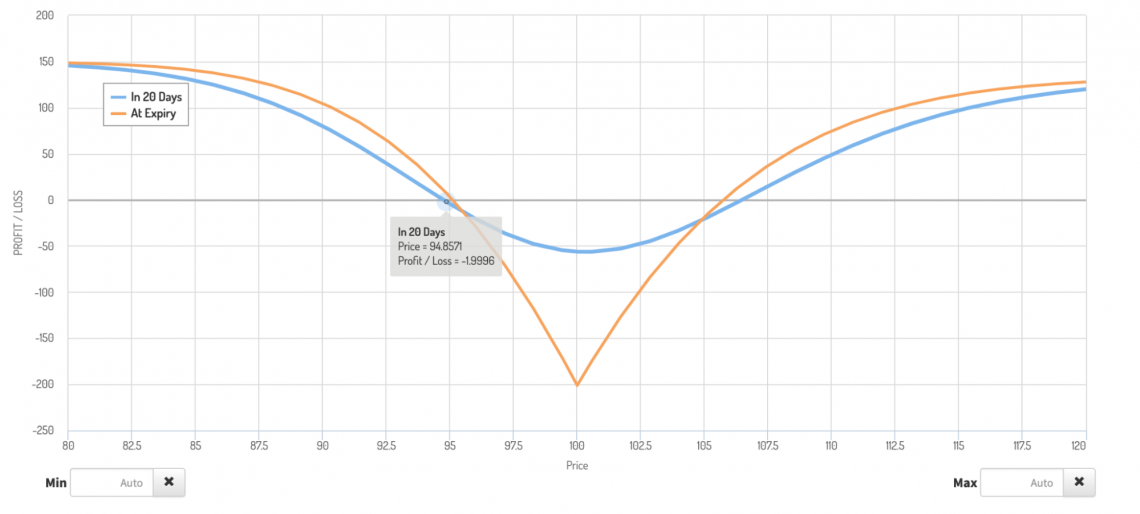

After 20 days, a lack of movement solidifies losses even more. The price must shift by roughly $5 for no unrealized losses. Past the break-even points, unrealized gains appear higher than before, as there is less time for the stock to move back toward the strike.

As the short contract expires, its time value diminishes more rapidly. This means close to the strike, and the spread is now the greatest. Past the break-even points, unrealized gains edge closer to their expiration date values.

Because of how the time value of a contract changes over time, this strategy will slowly show losses unless the price moves substantially. However, losses will start to grow quickly if the price remains at the strike close to expiration.

Traders inexperienced with risk management may stay in the position to try and avoid exiting at a significant loss. However, this exposes them to the risk of a naked position, which can lead to even greater losses. For this reason, it is recommended that only advanced traders use this strategy.

In addition to time, implied volatility plays an important role in determining the contract spread value. Because increased implied volatility increases the extrinsic value of the contract, shifts in implied volatility can significantly impact the price difference at the expiration of the first contract.

In this situation, the spread will be greater when the short contract expires, as the long contract now has greater extrinsic value. Therefore, the price must shift much more to break even.

Traders may opt to stay in the short position to try and exit the position for a lower price. But, once again, this exposes them to more risk.

Summary

Investors can create reverse calendar spreads with both puts and calls. The strategy involves buying a shorter-term contract and selling a long-term one at the same strike price.

A reverse calendar spread is typically the most profitable option when markets move significantly in either direction. Due to its complicated structure and large margin requirements, it is more prevalent among institutions than individuals.

The strategy is more profitable the farther from the strike market price is. This is because the strategy hopes to capture a difference in extrinsic value that diminishes throughout the trade.

The premium collected originally is the maximum profit if the spread is closed at the first contract's expiration. The max loss and break-even points depend on individual differences in extrinsic value influenced by implied volatility.

The strategy is for advanced investors, as the price shift can be rapidly close to expiration. However, this strategy can expose an investor to large or unlimited losses if the short leg is open.

The decision to enter an advanced position depends on an in-depth understanding of options trading and predicting movement in the underlying stock price.

Investors develop their outlook, in part, by using equity valuation, which depends on financial modeling.

or Want to Sign up with your social account?