Disequilibrium

Condition that signifies imbalance between supply and demand forces

What Is Disequilibrium?

Disequilibrium in a market-driven economy signifies an imbalance between supply and demand forces. This imbalance arises when the price of a product deviates significantly from the stable equilibrium point, either becoming excessively high or low.

It can be a temporary or enduring issue, indicating momentary or prolonged disparities within a market or economy.

Short-term disequilibrium arises from temporary disruptions in the market. It commonly stems from sudden occurrences like a rapid upswing in oil prices or the aftermath of a natural disaster.

Despite the initial disruption, the market tends to readjust over time naturally.

Long-term disequilibrium persists due to more profound issues. Structural problems, such as a misalignment between the skills possessed by the workforce and the requirements of businesses or policy decisions like intentionally maintaining low-interest rates by a government, contribute to this prolonged imbalance.

Addressing long-term disequilibrium proves to be more challenging compared to its short-term counterpart.

Beyond its influence on prices, it can occur not only as an imbalance in market conditions but also extend to the balance of payments (BOP) of a nation, presenting itself either as a surplus (where receipts exceed payments) or a deficit (where payments surpass receipts).

Key Takeaways

- Disequilibrium, a condition marked by an imbalance between the quantity demanded and supplied for a product or service, is pervasive in nearly all markets. This state can arise from factors originating within or outside a firm.

- Internally, firms may contribute to such state of imbalances by setting fixed prices for specific products or services. Externally, factors like the emergence of a pandemic, war, or natural disasters can also lead to this state of imbalance.

- Addressing disequilibrium can be approached through different economic philosophies. The laissez-faire and Keynesian approaches present possible ways to fix disruptions in the market.

- It can be short-term or long-term, indicating temporary or enduring imbalances within a market or the broader economy.

- Apart from impacting prices, it creates imbalances in market conditions and can affect a nation's balance of payments (BOP). This is evident through a surplus (when receipts exceed payments) or a deficit (when payments surpass receipts).

How Disequilibrium Works

When external influences impact the pricing of goods or services, it leads to an imbalance between the quantities supplied and demanded. The renowned economist John Maynard Keynes introduced this state of "disequilibrium" in the early 20th century.

Keynes suggested that substantial price changes for a product could trigger a period of imbalance, disturbing the typical equilibrium between supply and demand. According to Keynes, this imbalance leads to inefficiencies in the market and varying degrees of price fluctuations.

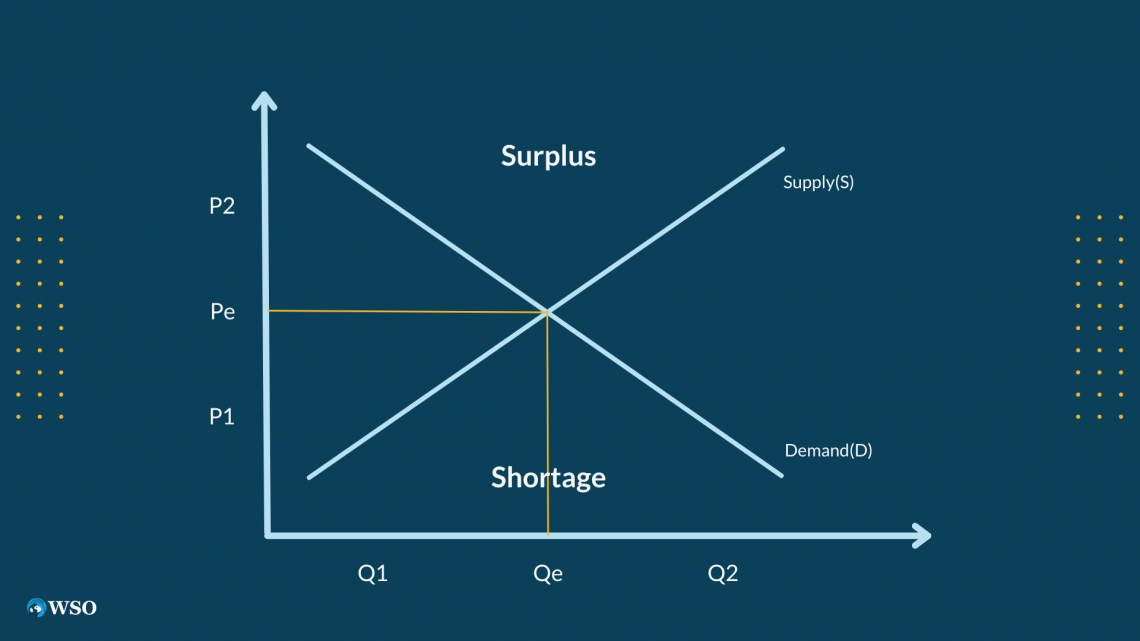

The supply and demand model has become a common framework for examining disequilibrium, illustrating how price alterations can contribute to market imbalances.

Modern economists often use the term "general disequilibrium" to explain the typical condition of markets. They acknowledge that financial markets today are influenced by many dynamic factors, making it challenging to achieve true equilibrium.

In an equilibrium market, there are no surpluses or shortages for a product, leading to price stability. It's like a balanced scale where market supply and demand are in sync.

The point where the demand and supply curves intersect defines the equilibrium in the market. Any deviation of the market price from this equilibrium signifies a state of disequilibrium, suggesting an inefficient market operation characterized by fluctuating prices.

Market forces naturally function to restore balance from imbalances driven by the profit motives of individuals. When certain assets are underestimated in value and others are deemed too high, individuals seeking profit, commonly known as arbitrageurs, step in to take advantage of these discrepancies.

They leverage price imbalances to their advantage, acquiring undervalued assets and divesting overvalued ones. This arbitrage practice gradually restores the market equilibrium as supply and demand are adjusted.

Disequilibrium in Action

In this hypothetical scenario, we observe the interplay of supply and demand for wheat in a market. The equilibrium price (Pe) represents the point where both suppliers (farmers) and consumers find it mutually beneficial to engage in transactions, ensuring a balanced market.

Let's see how disequilibrium occurs:

- Market Imbalance: Price Increase to P2: If the price rises to P2, suppliers are motivated to offer more wheat as it covers production costs and increases profits. However, consumers, faced with the higher price, may reduce their wheat purchases. This imbalance produces a surplus (Q2-Q1), creating a disequilibrium market.

- Surplus Correction: Market Forces at Play: With an excess supply of wheat, suppliers aim to sell quickly, prompting a reduction in the sales price. Economic theory suggests that the wheat price will eventually revert to the equilibrium price (Pe), correcting the surplus in a free market.

- Market Shortage: Price Decrease to P1: Conversely, if the market price falls to P1, consumers become more inclined to buy additional wheat (Q2) due to the decreased cost. However, suppliers may decrease their wheat supply (Q1) as the price dips below their production costs.

- This mismatch, where the quantity demanded outpaces the quantity supplied, points to a state of disequilibrium.

- Efficient Resource Allocation: Market in Disequilibrium: When there is either an excess or a deficit of resources, it signifies a market imbalance where efficient allocation is not achieved. In a freely functioning market, corrective mechanisms are anticipated to restore prices to equilibrium, thereby ensuring effective resource distribution.

Reasons of Disequilibrium

Disequilibrium in markets can be attributed to various factors, all influencing the delicate balance between supply and demand. Understanding these reasons is crucial for comprehending market dynamics.

- Sticky Prices and Fixed Pricing: When suppliers establish fixed prices for goods or services during periods of price rigidity. If demand increases during this time, a shortage occurs due to the inflexibility of prices.

- Government Intervention: Government-imposed price floors or ceilings can disrupt market efficiency. For instance, a price ceiling on rent may discourage landlords, leading to a shortage of rental properties and excess demand for housing.

- Labor Market Imbalance: Government-set minimum wages can create imbalances in the labor market. An oversupply of labor may result if the mandated minimum exceeds the equilibrium wage.

- Balance of Payments: It also occurs in a country's balance of payments when there's a deficit or surplus. Deficits, where imports surpass exports or surpluses, with greater exports, impact economic stability. Imbalances in import-export activities due to changes in trade agreements between countries can lead to disequilibrium in the balance of payments.

- Domestic Savings and Investments Imbalance: It can emerge when there's a disparity between domestic savings and investments. A deficit in the current account arises if domestic investments exceed savings, requiring foreign capital to cover the excess.

- Exchange Rate Changes: Revaluation or devaluation of a country's currency can cause market disequilibrium, influencing trade dynamics.

- Inflation or Deflation: Disequilibrium may result from price-level fluctuations, with inflation or deflation affecting market dynamics.

Disequilibrium Practical Example

Understanding disequilibrium becomes clearer when we look at real-world examples.

1. Russia-Saudi Arabia Oil Price War and COVID-19

Saudi Arabia initiated an oil price war against Russia, flooding the worldwide oil market with surplus supply. The objective was to drive down oil prices and exert influence on U.S. shale producers.

The Covid-19 pandemic led to global quarantine measures, drastically reducing travel and commuting. This resulted in a substantial drop in demand for oil.

The combination of the supply and demand shocks mentioned earlier occurred on April 20, 2020, when the price for WTI oil futures turned negative for the first time. Essentially, holders of futures contracts were paying others to take delivery of the oil.

This unprecedented situation occurred because the value of oil dropped to a point where holders preferred paying others to take it rather than incurring storage costs as pipeline capacity approached limits.

External forces, including geopolitical tensions and a global health crisis, caused such drastic shifts in supply and demand that traditional market pricing mechanisms were disrupted.

Prices became dislocated from their usual equilibrium, highlighting the vulnerability of markets to external shocks.

2. The Flash Crash Example

The Flash Crash phenomenon involves a sequence of sell orders that rapidly deplete all standing buy orders in the market, resulting in a swift and significant price drop.

This decline is often aggravated by the involvement of algorithmic trading systems, which react to the sell-off by introducing additional automated sell orders.

On May 6, 2010, the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunged nearly 1,000 points in less than 10 minutes. It was marked as the greatest collapse in history at the time.

Within an hour, the index lost nearly 9% of its value, eradicating over one trillion dollars in equity. The market ultimately bounced back, reclaiming 70% of its losses by the end of the day.

Initial reports attributed the crash to a mistakenly entered order. The true cause, as revealed by the SEC inquiry report, was a futures trader from the United Kingdom who admitted to attempting to "spoof the market."

This involved rapidly executing buy and sell orders for hundreds of E-mini S&P Futures contracts on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME).

According to the SEC report, a single order selling a substantial quantity of E-mini S&P contracts catalyzed the Flash Crash of 2010. This large-scale sell order created an unstable disequilibrium in the market, leading to an unprecedented and rapid decline.

How Is Disequilibrium Resolved?

Disequilibrium in the economy can be addressed through two main approaches.

Laissez-faire Economics

Laissez-faire economics believes in minimal government interference. This approach contends that allowing market forces to readjust themselves naturally leads to a more efficient and self-regulating economy. The idea is that markets, if left unhindered, will autonomously find a new equilibrium.

Throughout history, during economic decline, advocates of laissez-faire economics have maintained that minimal government interference is necessary.

They contend that markets possess inherent mechanisms for self-correction and equilibrium, eliminating the need for significant government involvement.

Keynesian Economics

Keynesian economics advocates for active government participation, particularly during economic recessions.

Theory suggests that governments should engage in fiscal activities, such as increasing spending and reducing taxes, to stimulate the economy artificially. The goal is to expedite recovery and minimize the duration of economic downturns.

Following the 2008 financial crisis, numerous governments implemented stimulus packages influenced by Keynesian principles. These measures involved infusing capital into the economy to mitigate the recession's impact and expedite the recovery process.

Modern Government Practices

Present-day economic policies often align with Keynesian principles, emphasizing proactive fiscal measures during economic downturns. Governments recognize the potential benefits of swift intervention, reducing the time spent in recessions and prolonging periods of economic expansion.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, governments worldwide implemented Keynesian-inspired stimulus packages to counter the economic fallout and showcase a commitment to active fiscal measures supporting markets and industries.

Disequilibrium FAQs

Equilibrium is attained when the quantity demanded matches the quantity supplied at a given price point. Disequilibrium arises when there is a disparity between demand and supply, prompting price and quantity adjustments.

Government policies such as price floors, price ceilings, or taxes can lead to disequilibrium by disrupting the natural market forces. For example, a price ceiling may cause excess demand, leading to shortages.

It can occur in two main forms: a shortage caused by an excess of demand over supply at a specific price or a surplus resulting from an oversupply relative to demand at that price.

It can be caused by various factors, including sudden changes in consumer preferences, shifts in production costs, government interventions, or external shocks impacting supply and demand dynamics.

Yes, it is typically temporary, as markets tend to realign over time. Adjustments in prices, quantities, and overall market dynamics occur as buyers and sellers, react to changes, ultimately restoring the market to equilibrium.

Authored and researched by Rani Thakur | LinkedIn

Free Resources

To continue learning and advancing your career, check out these additional helpful WSO resources:

or Want to Sign up with your social account?